My obsession with progression meters, and the art of shaping the player experience

7.94 per cent.

The devil, they say, is in the details. This makes grim sense to me, as I'm being tortured by what seems to be my own personal demon, a foul creature which stabs at me from depths of minutiae that I can never seem to delve into to any satisfying extent. Percentages roar angrily around my head, and numbers course relentlessly through my veins. I wasn't always like this.

I only wanted to play Shadow Of The Tomb Raider.

I hadn't played a Tomb Raider game for about two decades, but I thought I'd give this one a go for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I was curious to see how far the series had come over that time. Secondly, it was free with Xbox Games With Gold.

So, I played for a few hours. The graphics were very pretty, Lara sort of looked like a real woman, and the game was fun (if somewhat derivative). I enjoyed myself. Eventually of course, the call of real life could no longer be ignored, so I turned the game off and played the role of a fully functioning human adult. The next day, I returned to the game.

That's when everything started to go wrong.

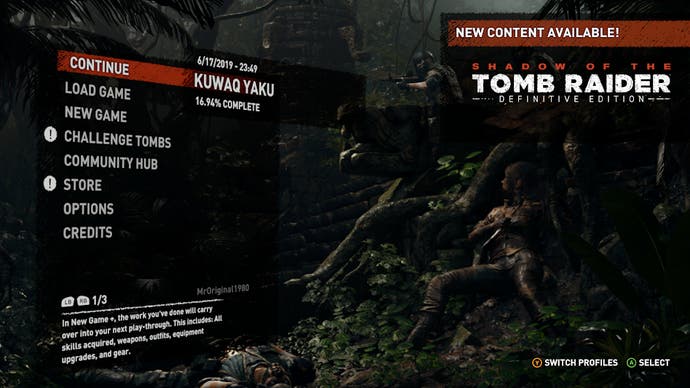

The title screen now proudly displayed a completion percentage. A very specific percentage. 7.94 per cent to be exact. So, I had seen 7.94 per cent of everything the game had to offer. Or was I perhaps 7.94 per cent of the way through the story? Hmm.

I loaded up my save, and dug through the menus to investigate. I found... nothing. Nothing to break down that percentage on the title screen, nothing to tell me what the numbers meant at all. No sign of how or why that percentage had been generated.

Somewhat disturbed, I quit without playing. I soon found that for some reason - perhaps because my brain had set itself up for answers that were never provided - I had developed an unscratchable mental itch. A desire, a need, to break down and understand how and why I was progressing in the games that I was playing.

I tried to get an interview with somebody from the Shadow Of The Tomb Raider development team, to help me understand that title screen percentage, and numbers of this kind in general. Although the Square-Enix PR staff were incredibly friendly and helpful, in the end, such an interview could not be arranged. I tried to forget about it by playing some other games and, well... that didn't quite work out.

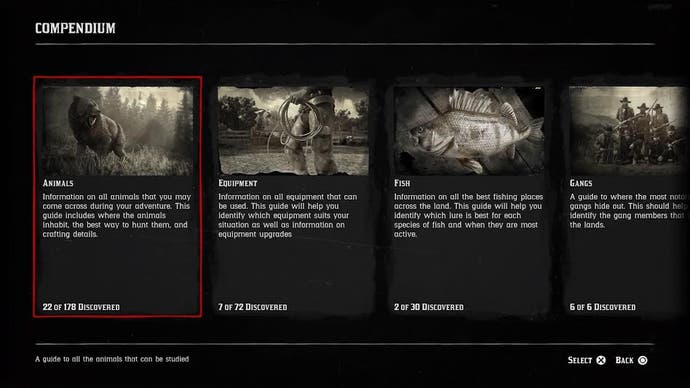

GTA 5 was a bad place to start, what with its completion percentages by character. Wolfenstein Youngblood was kind of satisfying - by examining my save file, I could see overall completion percentage, as well as a detailed breakdown of other tasks and stats in the game - but it didn't exactly take my mind off things.

Then I made a truly horrifying discovery, one which self-defence systems in my brain had erased from my memory. The Witcher 3, XP progression bar aside, has no completion meters of any kind. None at all! So much to do, so many hours of content, and no bars or percentages to measure and track what I've done and what I've yet to do.

I retreated to the safety of the progression-stat-heavy Shakedown Hawaii, and then it hit me. Of course! The developer of this game could help settle my new obsession, and explain how he sorts and expresses stats and progression. My requests for an interview with Brian Provinciano, however, were swallowed by the internet. Perhaps my desperation had begun to leak into my emails. I can't be sure.

By this point, I'm starting to ask questions about myself as well as the games that I'm playing. Why is it important to me that I see my progress measured in tidy bars and numbers on the screen? Why do I get a strange sense of satisfaction, and a boost to my motivation, when I see that I've almost reached the end of a story, or I only have one or two collectibles left to find? Why, when a menu tells me that I have another character level to reach, or that my equipment could be better, am I compelled to push forward and hit that next milestone?

Thankfully, there are two experts on these matters that, miraculously, did not flee in terror at my enquiries regarding such statistics and their use.

Celia Hodent is a UX expert who has previously worked with companies including Ubisoft, Epic Games, and Lucasarts. UX is a relatively new discipline in the industry. It's a slightly tricky concept to explain; it means 'user experience', with the emphasis on 'experience'. A common misconception is to equate UX with UI.

"User Interface is definitely part of UX," Hodent tells me. "It's definitely important to understand the information architecture, the interaction, the layout of the menus, icons, definitely. But UI is just a little part of UX. UX is really everything players are going to experience, including marketing and community management [...] [UX means] not just talking about UI, but talking about sound design, about game design, about level design, about marketing, and community, toxicity, all that."

Hodent realised that UX wasn't as widely understood within the video game industry as it is in other areas of business, and there was no book to help teach people about its application to video games - so she wrote one. The Gamer's Brain: How Neuroscience And UX Can Impact Video Game Design isn't cheap (its primary market is students and industry professionals), but it is absolutely fascinating. The first half of the book talks about several areas of cognitive psychology, and then the second half explains how and why this is relevant to game development.

"My background is in cognitive psychology," Hodent explains, "how the brain works and learns. I started my career using that knowledge for educational games, for educational purposes. But then I started to work at Ubisoft in 2008. They always want to make their games more enriching for players, [and] I quickly realised that all that knowledge about how the brain works is useful for any game, because playing a game is a learning experience. You have to discover lots of stuff, you have to understand the controls, you have to understand the mechanics, the storyline, your goals, etc etc. So you have a lot of things to process, and you also have to master the game. So all that happens in your mind, and I soon realised that all this knowledge is not only useful for educational games, or serious games, but for any game."

Hodent left Ubisoft years ago, but the company has clearly embraced the concept of UX. This becomes immediately obvious when Scott Phillips, game director on Assassin's Creed Odyssey, explains the process of deciding what to quantify when it comes to progression stats.

"Generally, the question of what to affect with a progression system begins with the question of what gameplay and mechanics are in the game," Phillips says. "We need to look for what mechanics are the most impactful in the player experience. We need mechanics that can be progressively made better to give players a sense of long term positive improvement - vertical progression - or mechanics that can create interesting choices for players based on their playstyle - horizontal progression... For players, being able to see progression information allows them to see that they're getting better at the game, mastering the mechanics, and growing in tune with the character and story. Ideally, this progression can also be felt in the experience, which, if balanced properly, makes the player feel increasingly powerful but maintains an enjoyable level of challenge."

This makes perfect sense, and I start to understand why I crave validation from numbers, bars, and other visible signs of progress. I know I'm moving forward, getting better and stronger; these elements confirm that to me. That confirmation of my progress, I think, is almost a reward in and of itself - evidence that all the hours I've spent in a game have achieved something. Hodent elaborates, framing this sense of progression in wider, more human terms.

After briefly explaining the concepts of extrinsic motivation ("when you do something to gain something else") and intrinsic motivation ("the things we do just for the pleasure of doing them"), she says: "The main theory of intrinsic motivation that is the most reliable so far is called self-determination theory, or SDT for short.

"This theory explains that we are more intrinsically motivated to do certain activities when these activities satisfy our needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Progression bars are super useful for competence. When you see that you are progressing towards something, you feel that you are getting better at it [...] it's not just to show that you've reached a certain goal, and you're going to have a specific reward associated with that goal. You also feel better, because you see yourself progressing in doing certain things.

"Whatever you do in life, if you try to learn to play an instrument, like the piano or the guitar, or you're trying to lose weight; if you don't see yourself progressing every day, at some point you're just going to quit. If you make some efforts to lose weight, usually the first few weeks you lose weight every week, so you're happy, motivating you to keep going because you see a progression towards your goal. But if at some point you keep making these efforts to not eat garbage and you see that you're reaching a plateau, which always happens at some point when you're trying to lose weight, this is when a lot of people just quit. Like, 'Fuck it, why am I going to keep making the effort when I'm not progressing any more?'. Same thing if you learn to play the guitar; if at some point you don't feel like you're making any progression, you're going to quit."

Phillips unintentionally echoes these sentiments, further proving the value of UX to game design. "If there was any universal rule to the psychology of progression," he says, "I would state it as: start small and end big. Human beings innately understand going from weak to strong, from 0 to 100, from beginning to end. In video games, we use progression mechanics that align with existing instinctive mental models that are reinforced in daily life. In terms of quantifying progression, we do that based on the system and the overall needs of the game and the desired player experience. So it's very customised to each game and each system.

One of our driving philosophies on Assassin's Creed Odyssey is called the Player Experience of Needs Satisfaction, which says that if a game makes players feel autonomous, connected, and competent" - the fundamentals of self-determination theory, remember - "it can expect sustained engagement from those players. This concept was applied to every system we created, and I think it helped reinforce how we wanted players to experience the game."

What I find particularly interesting about this is that it shows video games in a psychologically healthy light. They are a potentially limitless source of intrinsic motivation. They can offer you a sense of progression in a diverse range of ways, which results in positive feelings such as a sense of accomplishment. My attachment to on-screen evidence of this progression, perhaps, stems from the comfort to be taken in a persistent record of the results of my gaming efforts.

Then there's the way something as simple as a percentage or a progression bar can give us a comforting sense of context for our actions. "We love to understand where we're at as humans," says Hodent. "Even if we have to wait at the bus stop or the metro station, just knowing how much time is left before the train arrives is reassuring, because you know exactly what to expect. It's very stressful for us when we wait and we don't have information. This is usually how people get mad, when they don't get information about the status of something."

One thing that Hodent goes to great pains to reiterate in The Gamer's Brain, is that in order to be fully effective, UX must be considered from the earliest stages. Again, these lessons seem to have been taken to heart at Ubisoft. "Design for progression begins immediately and is generally well established when a game is first pitched," Phillips tells me. "For a big open world RPG like Assassin's Creed Odyssey we needed to convince both ourselves and stakeholders within Ubisoft that we had the design and systems to deliver on the RPG pillar of the game. This meant that we needed to be sure that we could create sustained long-term engagement and exciting possibilities with our systems.

"Actual implementation of the mechanics and their accompanying HUD/menu elements is usually at a first pass playable state by the First Playable milestone within the first year of production [...] By Alpha - one year before ship - we had the base of most of the systems functioning and roughly balanced, so that playtests could begin in earnest. We didn't necessarily have all of the HUD/menu elements, and only had rough tutorials and teaching flow - so we often heard from players that they didn't understand or engage with certain systems. With a giant open world RPG like Assassin's Creed Odyssey we needed a lot of data to help drive our decisions of what needed tweaking and which way to tweak it. Playtests as well as long term director reviews were the best way to get that data.

"One of the areas that get the most iteration is the actual presentation of all of these progression mechanics to the player - the UX or user experience. We tweak and change and test many variations outside of the game. Once it's in the game, it undergoes further iteration on placement, size, font, appearance timing, etc. before finally having an art pass in order to bring everything together in a cohesive manner with proper sound effects and animations to celebrate changes in the progression systems."

So, there's a lot of tweaking, testing, and re-tweaking that goes into something as ostensibly simple as communicating progression to the player. This shouldn't really come as a surprise; no matter how well any developer has mastered their job, they're still human. "As humans, we are biased," explains Hodent. "When you create a game, no matter what your job is in the game development process, you do it through your own lens. We have the curse of knowledge. Perception being subjective, it's really hard to anticipate what is obvious [to the player] because you have all that knowledge about the game and what it is, and you have all your own cultural references. To you it's going to be obvious, but then to the end player, even if it's hardcore players with very strong expertise in your game genre, they might not get it, because they are not you, and we are all different."

I never thought video game development was easy, but Hodent and Phillips really opened my eyes to how much time and effort goes into even the most seemingly minor aspect of a game. Clearly, such work pays off; a good game gives me pleasure in a way that no other medium can, and being able to quickly and easily track my progression adds another layer to the experience. Maybe I've become a little too enamoured with the statistical side of things, but still.

UX as a discipline isn't quite as pervasive in the industry as it arguably needs to be ("I think we're gonna get there, slowly but surely," Hodent tells me), but its use is certainly more common and in-depth than it ever has been before, as Phillips explains in the context of expressing player progression. "In the nearly 20 years I've been making games, progression has become much more of a science while remaining undoubtedly an art. With user tests, data tracking, and data visualisation, each game makes us better at determining whether our designs are working, and if they're not working - why. We know much more about things like eye saccades, user psychology, how players consume information, when they're able to focus, where best to place information we want players to see, etc. We have whole departments now that help us evaluate the games including their progression systems. The discipline of user research is attracting more scientists and researchers, and we're learning from other industries and their practices. Finally, as the video game industry and the developers mature, we have much more experience with successes and failures of user experience than were ever available before."

Then it hits me. I had never become obsessed with measurements of my video game progression in my youth, because the expression of these measurements has evolved alongside the games that they support. We enjoy an embarrassment of riches today, when it comes to the depth and breadth of progression breakdown available. I'm leaning heavily on the "embarrassment" rather than the "riches" when I feverishly scan the menus of my games, but I'm the exception rather than the rule. I'm quite sure that most of you can consume a reasonable amount of statistics in the morning, a few progression bars in the afternoon, and a sensible dinner.

This is my third feature for Eurogamer, meaning that it represents 33.33 per cent recurring of my total EG output so far. Unless you're going by word count, in which case it's probably going to be more like 41.7 per cent by the final draft. If I (optimistically) try to get another two written and published within the next six months, that means I've achieved three out of five, and the progression bar would have passed the halfway mark by a satisfying chunk.

Oh no... it's happening again...