Nine ways the the 8-bit era made gaming what it is today

Going back to the future.

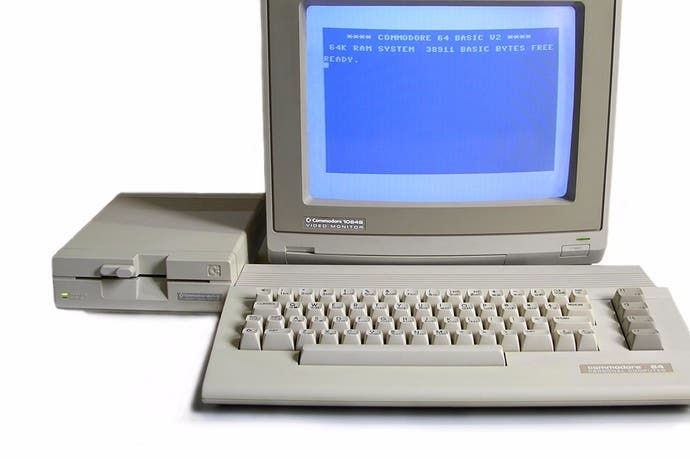

The mixed reception for the Spectrum Vega and Elite's maligned Bluetooth keyboard may have dulled the resurgence of 8-bit gaming lately, but the announcement of the Spectrum Next computer proves that there's still life - and love - in the old machines. And it's with good reason; the Eighties 8-bit home computer software scene in the UK was a hotbed of invention and discovery. From the primitive games of the ZX81 to the system-stretching marvels on the three most popular machines in the UK, the ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC and Commodore 64, new concepts, gameplay elements and marketing ploys were devised constantly throughout the decade. Many of them echo today, and indeed contemporary gaming owes plenty of debt - or at least knowing nods - to these trailblazing pioneers. Here are ten examples of how home computer video games of this era made helped make gaming what it is today - for better or for worse.

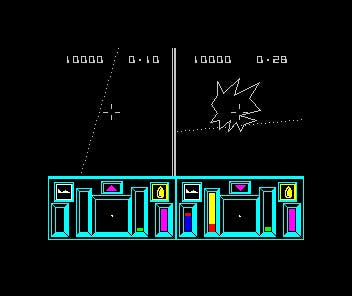

Split-screen gaming

Local multiplayer may be dying out in this age of internet gaming, but there's no doubt it was a key step in getting there in the first place. Back in the 80s, the majority of home computer gamers played alone, so gaming with a friend always felt fresh and oddly exciting. Ocean's Top Gun, a license of the US Airforce advert/movie was an unexpected hit for the Manchester software house as, after a series of disappointing duds, expectations were low. Focusing on the air combat theme of the movie (let's face it, there was little else to it), Top Gun was one of the first games to concentrate solely on split-screen local multiplayer. Each player took control of an Eagle jet fighter with the only purpose to shoot your opponent down three times. Top Gun had a single player version, but its AI was poor and the mode felt tacked on. Sound familiar?

DLC

Of course, it wasn't downloadable, but publishers selling extra content to extract more cash out of punters is hardly a new thing. There are plenty of examples, but perhaps the closest in terms of the longevity that DLC can provide (as well as the cheekiness of unlockable disc content) is with strategy titles. Julian Gollop's Laser Squad came with a small set of scenarios including eliminating a troublesome arms dealer ("The Assassins") and escorting a set of captives from an underground prison ("Rescue From The Mines"). The game was a forerunner itself thanks to its line-of-sight combat and action-point driven gameplay, these and other tactical elements combining neatly with a simple and intuitive interface. Its original 8-bit release contained just three missions, with a further two audaciously offered via mail-order. A subsequent re-release included all five of these missions with yet another two ("The Stardrive" and "Laser Platoon") available by mail-order. Thanks to a stiff AI challenge, plus the two-player option, Laser Squad and its numerous missions were good value for money, despite the nagging feeling customers were being exploited, albeit thanks to a superbly-balanced game.

Open world gaming

Today, many fans fawn over the free open worlds of games such as Fallout and Skyrim. Able to roam anywhere, do anything, and be anyone, the sheer level of choice and freedom is clearly a popular concept. 30 years ago it was a different story, but there were still many examples. Perhaps the finest was the space adventure Elite, published by initially on the BBC computer by Acornsoft and created by David Braben and Ian Bell. Using wire-frame graphics, Elite set the player up with a small amount of cash and a basic space ship named the Cobra Mark III. Despite the presence of a number of side-missions, there was no central plot to follow - you were simply free to wander the universe, making as much money as possible to upgrade your ship and status. Elite's freedom stemmed not only from this, but also the way you could go about it; whether by trade, mining, bounty-hunting or piracy, commanders were able to achieve their goals as they saw fit.

Motion capture

With graphics becoming increasingly more realistic with each passing generation, motion capture technology has advanced tremendously in the last 20 years. Now, whole studios exist just for the purpose and even the humblest indie developer effort can feature this method of authenticating human movements. Games such as Prince Of Persia and Another World may have caught the eye, yet motion capture had already been used primitively on the 8-bit computers. A software house named Martech - most famous for its digitized card game Sam Fox Strip Poker - employed another page three star, Corinne Russell, to act as cover and in-game star of the otherwise unremarkable run-and-whip game Vixen. Martech filmed Russell for two solid days as the model ran, jumped and crouched in a skin-tight leotard; filmed on a simple video recorder with a black background and a vast array of lights, the results were then hand-drawn from the images. While this unsophisticated approach may be a long way from the techniques devised just a few years later, the animation and movement of the main character remains impressive in an otherwise dull game. And according to former Martech owner David Martin, the motion capture sessions proved strangely popular with his employees...

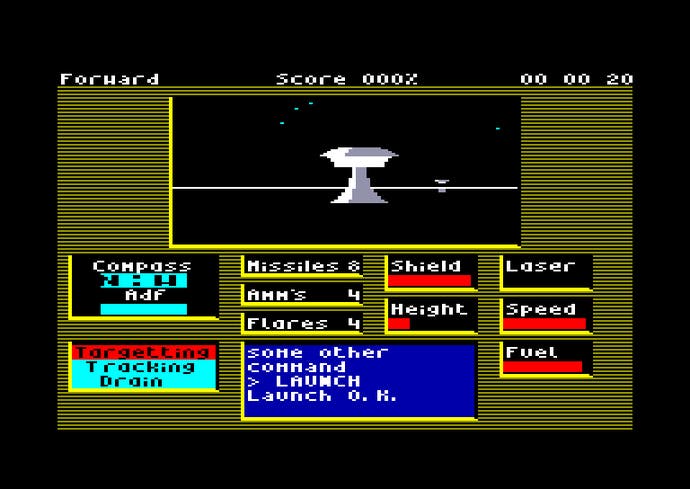

First person

There was a time when games relied on a strict third-person viewpoint - your avatar was almost always visible on screen, whether it be car, person or spaceship. Space shooters in particular may have long boasted of a first-person viewpoint, but ground-based equivalents were rare, and usually wire-frame, such as Novagen's impressive Mercenary. In 1986, Incentive Software, based in Hampshire, began developing a technique called Freescape - a combination of the words freedom and landscape - which would give players the chance to move freely around a solid game world in first-person and interact with its various elements and structures. The result was Driller, a game that moved at a snail's pace on the 8-bit computers (one frame per second!) yet was an astounding achievement with such limited memory capacities. Driller and its countless follow-ups also created another trend by essentially using the same engine over and over again, until Incentive got bored and moved into business applications in the early 90s. By then the mantle had been taken up by others, and it wasn't long before a little game called Doom was unleashed upon the world...

Age classifications

Although the industry today voluntarily regulates (via PEGI), and on extreme occasion can still fall foul of the BBFC, there was a time when the latter organisation didn't regard videogames capable of creating content risqué enough for age-related censorship. CRL's Dracula (Dracula Unbound: The Story Behind The First 18 Certificated Videogame) changed that and the gory adventure and its brethren (Wolfman, Frankenstein, Jack The Ripper) were key in changing the way videogames were perceived by the BBFC and the general public. CRL's horror adventures used words to frighten, with the occasional gory image proving less of a concern to the powers that be. Today, the combination of realistic graphics and adult storytelling means all games are rated, with many deemed legally unsuitable for under 18s by the aforementioned PEGI.

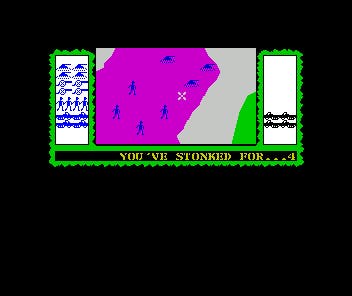

Real-time strategy

Like survival horror, real-time strategy is a genre that many will tell you stretches back to way before its most famous progenitor. The former's poster child was Resident Evil; the latter's Westwood's famous Command & Conquer series. For survival horror, many experts revert back as far as the Atari 2600 game Haunted House; for real-time strategy, 1983's Stonkers on the ZX Spectrum. Stonkers was the result of a brainstorming session at Liverpool's Imagine Software. Already a big name thanks to its promotional prowess (and some of its games weren't too bad either), the Imagine bosses had decided that they needed a strategy title to go with its range of arcade games. Veteran coder John Gibson helped come up with Stonkers' design - a war game with a difference, that required the player to keep constant track of their forces and supply and move them in real-time, rather than in turn. The impact was not immediate - turn-based strategy games remained dominant throughout the decade - yet its clear Stonkers is an early example of what would, a dozen years later, become a very popular genre.

Customisation

OK, so we're not talking Fallout-esque how-long-shall-I-make-my-scar levels of customisation here; but long before the lone wanderer, sole survivor or any other poor Vault-Tec victim emerged blinking from the depths, there were plenty of other games that offered flexible characters and screen designs. Having had a sizeable hit with the space adventure, Tau Ceti, author Pete Cooke decided to include a novel feature into its sequel, Academy. Before jetting off on any number of pilot training missions, the player was able to completely design the interior of their craft (or Gal-Corp skimmer as it was known in-game), from the size of the various screens and instrument panels to their location and position. Like many aspects of Fallout's character generation, the decisions the player made were ultimately cosmetic, but the depth of interaction and customisation felt like a whole new world back in 1987.

Movie licensing

Despite a small number of low-key exceptions, the early part of the 80s saw games companies studiously ignore the complication (and cost) of official movie licenses. Activision and its acquisition of the rights to a certain supernatural comedy changed all that forever. Ghostbusters was a worldwide box-office phenomenon, and the development of the game was handed to David 'Pitfall!' Crane. Written in an alleged six weeks, Crane produced the Commodore 64 and Atari 800 versions, with further ports appearing on multiple other formats.

An admirable attempt at recreating the hit film on limited technology, the original Commodore 64 version was most notable for its speech, and although the game perhaps wasn't the finest, the movie tie-in helped create a sales behemoth. The industry woke up, and two years later software houses such as Ocean and US Gold were devoting entire budgets and departments to predicting the next big movie hit, and then acquiring its license.