How Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice was made as an 'indie triple-A' game on a tight budget

There was a shopping trip to Ikea along the way.

Ninja Theory detailed how it made 2017 adventure game Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice with triple-A production values on a tight budget as part of a talk during this year's Game Developers Conference.

Commercial director Dominic Matthews explained how in 2014, with work on Capcom's DmC: Devil May Cry wrapped up, the studio looked at what to do next.

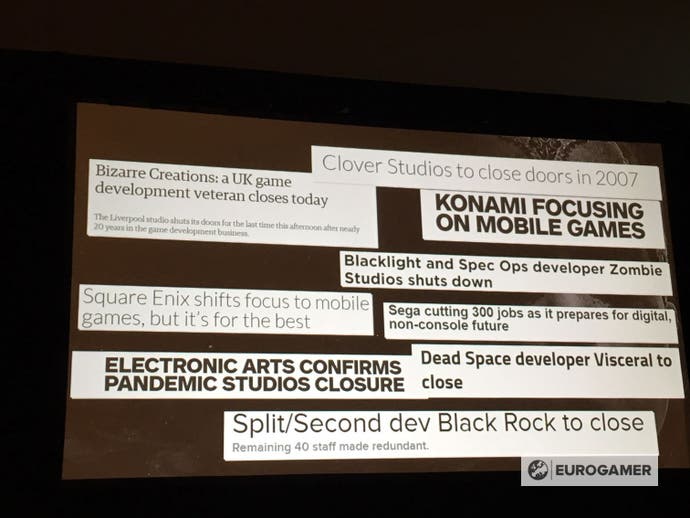

Ninja Theory pitched to publishers a project codenamed Razer, a "big games a service title" that never saw the light of day. A reason was because Matthews and the team found the industry had shifted into a position where middle-tier teams like themselves couldn't survive.

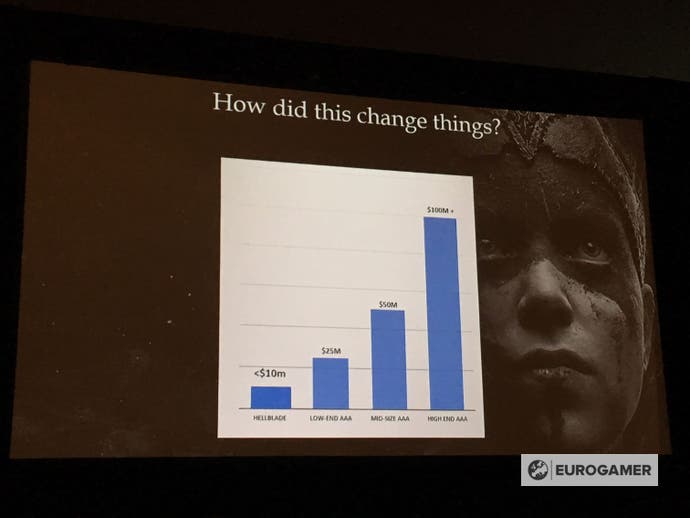

"It was a difficult market for studios like us. This was down to the triple-A arms race as we see it," he told attendees, including Eurogamer, at a talk titled 'Breaking through: Psychosis and the making of Hellblade'.

"The $60 price point meant developers and games can't compete on price and instead have to compete on size and scale and scope. It meant over the years games got bigger and bigger, teams have got bigger and bigger, and costs have got bigger and bigger.

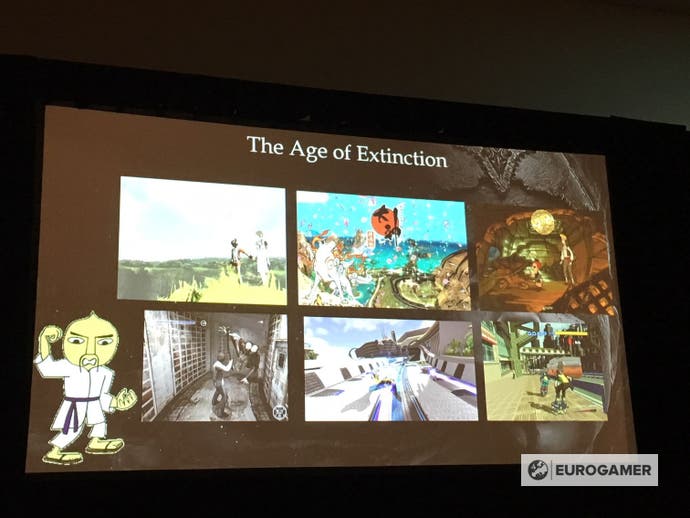

"It mean genres that thrived on years gone by cant survive no more, as they cant appeal to enough people to be justified."

"It's not huge, but we have a fan base that loves what we do," he continued, "but we're left with a choice where we ramp up our team size to make a game to appeal to many millions of people are risk sacrificing our core values and creativity in the process, or to walk away at that time [from] 15 years of development in the console business. We didn't want to do either of those things."

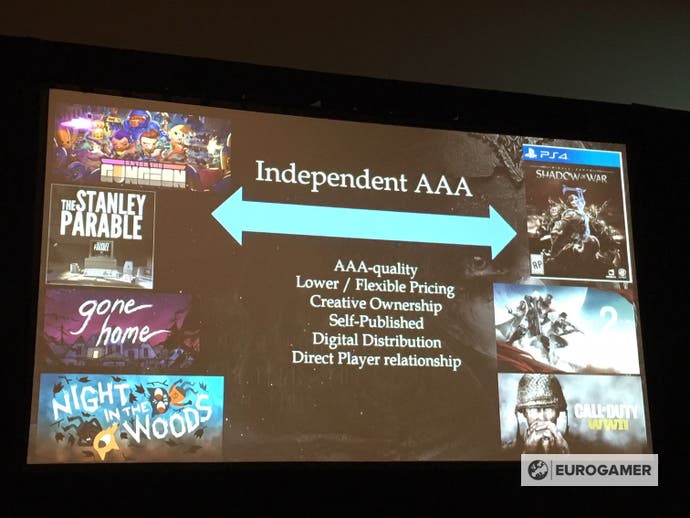

Matthews explained there are "two extremes" in the market - indies with huge creativity creating new genres, and huge publishers with "phenomenal production values" that produced games in a narrow band of genres that could help them "survive at the top end".

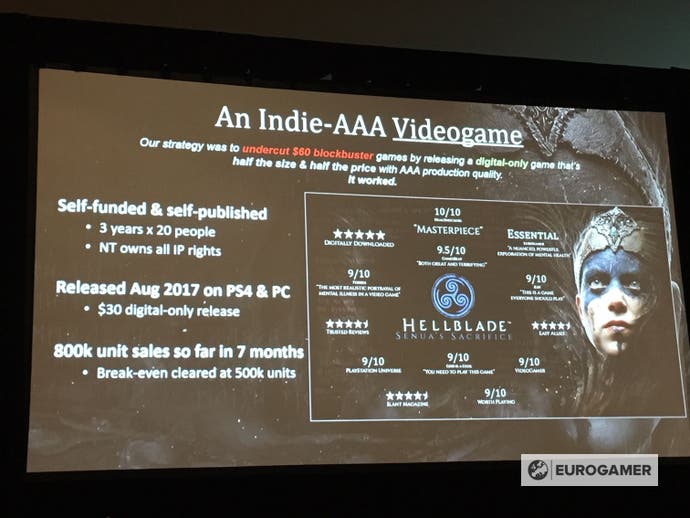

"There's nothing that sits in the middle of those two," he said. "This is the space that we call independent triple-A, and this is making triple-A quality games but they can be offered at a much more flexible price... making the game at the size and the scope we want to make and price it appropriately."

It's this space that Ninja Theory attempted to occupy with the development of Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice. With income sourced outside of a traditional publisher model - including support from the Wellcome Trust - the aim was to make a self-funded game with full rights and creative freedom for the team.

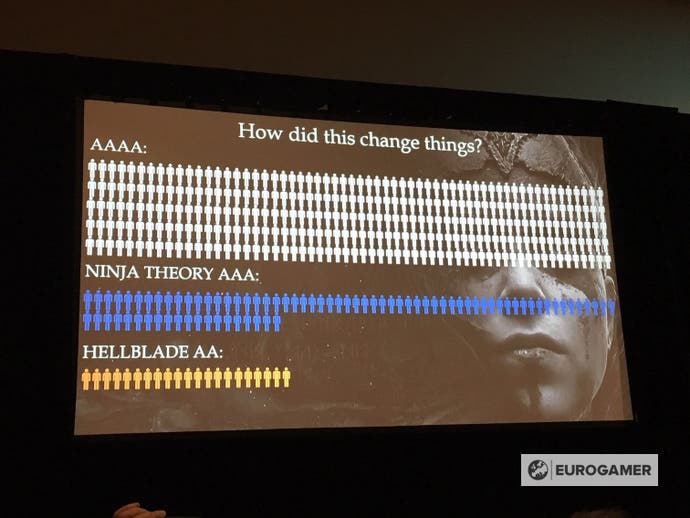

It did, however, mean a change to the way the game was developed compared to previous projects. For one, there was a huge difference in budget, "something far smaller than what we'd usually work with for a triple-A game".

The team size - one of the biggest costs in any project - was reduced, with the responsibility of many disciplines falling to a single individual. In total, around 20 staff worked on the game across three years - compared to around 100 on its previous games.

"[We had to be] very innovative and creative [to] deliver the quality and quantity we needed," Matthews explained. "The key to this was having the mindset and the attitude that we would never sacrifice on quality, and it wasn't a question of can we do it, but how?"

One example was Ninja Theory's approach to performance capture, something it's well known for in its previous games such as 2007's Heavenly Sword and 2010's Enslaved: Odyssey to the West, and a fundamental part of how the game would tell its story.

A cost-cutting decision was instead of flying staff across the world to purpose-built facilities to shoot their scenes, they converted their boardroom - the most suitable space that had in their offices - into a motion capture studio.

Needless to say this was an unusual approach. "Our attitude was - let's give it a go. If it doesn't pay off, we'll try out something else," Matthews said.

The team had to get creative in building the space. Table poles and ceiling lights were sourced from Ikea and Amazon respectively, while gym mats were used to coat the flooring.

The home-made approach worked. In the end, for the same cost as flying out a team to visit an external studio for just 3-4 days, they built their own from scratch, and could use it over the entirety of the project, enabling staff to set up and record additional animations whenever they were needed.

"An important point on this is the quality of the data that we gained from this was in line, if not better, than what we achieved before," Matthews said. "The important point is what comes across on screen is not in any way compromised. If it was, we wouldn't have done this."

This attitude was the same with multiple disciplines across the game. The capture studio was also used for their voice over recording using binaural microphones, using the opportunity to create something "incredibly experimental".

They also used live action actors - who performed in costume in front of green screens - to create other cutscenes. The team was sceptical of the practice - combining full motion video with in-game cinematics is unusual on paper - until press visiting the studio watched these scenes and couldn't notice the difference. "That was a job well done," Matthews said.

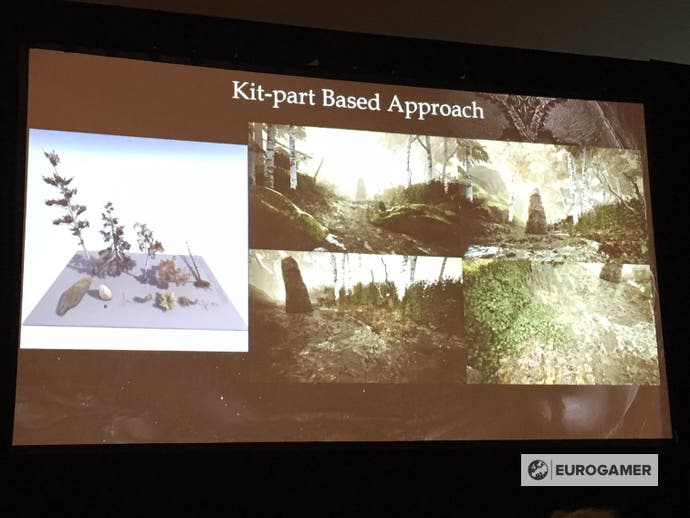

In-game environments also adopted the same approach, with artists focusing on just a small number of high quality assets. Instead of creating new rocks, the same few were reused in different ways, sunk into the ground or painted over with moss, for example, allowing them to create "high quality environments without a huge amount of bespoke content".

Elsewhere, textures were created using a handheld 3D scanner, helping construct human anatomy and materials such as textiles on a budget, while still "delivering high level realism".

And outside of the game, the team wanted a full and frank dialogue with its community. It announced the game early - three years ahead of release - and told its story across 30 development diaries, fostering a deeper connection with the studio's fans. It helped achieve pre-order numbers "way beyond our expectations", giving the team a boost to marketing efforts as the game approached release.

In the end, by keeping four 'triple-A indie' pillars in mind - being flexible with pricing, achieving a low breakeven cost for the project, a focus on community building and maintaining a creative focus - it helped Ninja Theory create a triple-A game at half the price and half the size, without compromising on quality, or giving the rights away to a publisher.

When Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice released on PS4 and PC in August 2017, it received rave reviews on release, and most recently nine BAFTA nominations including Best Game.

The flexible pricing also worked; the project broke even at half a million sales, and has managed around 800,000 copies sold to date. With an Xbox version recently announced for an April release, we can expect that number to continue growing.