Observation is like an arthouse accompaniment to Alien: Isolation

Ctrl, alt, delete.

When they're chalking up the greatest games of this generation, my belief - though maybe it's more of a hope - is that Alien: Isolation will find its place amongst the more predictable choices. An extended slice of slow-burn horror, and a smart piece of sci-fi, it's one of the rare occasions when a licensed game matched up to the source material. For my money, it's the single best Alien experience since the series' 80s prime.

Forgive me, then, for getting a bit excited about Observation, because it's what some of the team behind Alien: Isolation did next. Well, in a roundabout way it is, at least. Jon McKellan worked across various parts of that particular game for Creative Assembly - most notably on Isolation's exquisite UI - and left shortly after its completion, taking on a short stint at Rockstar on Red Dead Redemption 2 before starting out on his own. McKellan had a killer idea for a sci-fi game, and so recruited his brother alongside a childhood friend to help create it as part of new studio No Code.

It's not that straightforward, though - life never is - and while the contracts were being drawn up and settled for McKellan's grand sci-fi idea the team filled its time with a small sketch of a game called The House Abandon. A horror-tinged text adventure, it proved successful enough to spin out a full-fledged game, Stories Untold, which itself went on to win a BAFTA last year. So you might call that a success, too.

Now that particular diversion is out the way, though, No Code has been able to get back to business on what it set out to do. Not that the last couple of years have been a waste at all. "It gave us a bit of confidence," McKellen tells us after we play through a short demo through Observation, the final fruits of that idea. "What you're playing isn't a million miles away in terms of structure - at the time it felt pretty weird, and Stories Untold allowed us to road test some of those ideas."

Observation is a contemporary sci-fi, set some seven years in the future aboard LOSS - a station orbiting the earth, modelled closely on the International Space Station. Like its inspiration, it's a fascinating hotch-potch of modules and tech, seemingly cobbled together like some interstellar Katamari. It's that tech that's at the heart of Observation; at times antiquated, often stark and lent some kind of grim menace as the station's innards blink and hum in the loneliness of space. Oh, and you're playing the part of that tech here too.

"I was reading a lot of articles over the years about Alien, and people dissecting it," McKellan says of Observation's genesis, "and one of the things that stood was someone had written an article about what Alien was like from the alien's perspective. It's about an animal born in an unfamiliar environment, and everyone's trying to flush it out. If you take things from a different perspective, it becomes quite interesting.

"I started looking at other films, other tropes, and the evil AI is something that always comes up. When you flip that perspective, it's not necessarily evil, it's just because of its code is failing it. It's not human and it's making these involved choices without the tools to do that. I started taking it from there - all these situations you're familiar with, with the AI doing all these things."

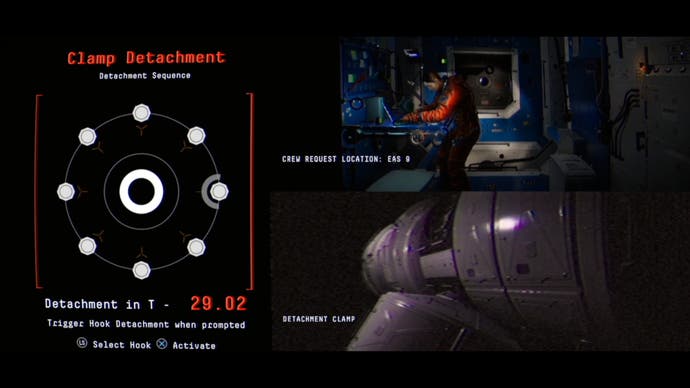

And so, in Observation, you're the ship's AI SAM (short for Systems, Administration and Maintenance) rifling through systems and switching between cameras, watching the story unfold while - initially at first, going from the short demo to hand - not entirely sure of your place in it. There's a tug of sinister forces, the suspenseful burgeoning knowledge of some other power waiting in the wings while you fumble through operating systems in order to help extract astronaut Emma Fisher - the only contactable survivor of an mysterious catastrophe that has befallen the space station.

It's a game rooted in confusion and noise, told expertly through the soft static of CCTV feeds and blunt computer interfaces that all hold that same aesthetic that made Alien Isolation sing. "First and foremost it's about function over form," explains McKellan, elaborating on an area he knows well after his UI experience on Isolation. "It's still going to be useable by humans, but it's not a human interface. There aren't symbols representing categories, because that's not how SAM would see things - it's all text-based, and it's all very sparse and limited, but we still want it to feel cinematic. And it's about paying homage to every sci-fi game since the late 60s that's had screen graphics, and this beautiful evolution from projected film graphics to hologram graphics, and having this retro look and making it feel quite contemporary. We've got this grounded feel, like you're using DOS."

In Observation you're playing as a machine, but in its opening stages the game is lent a uniquely human edge by the presence of Emma. She prods you into action, comments on your fumblings and mistakes and guides you through unfamiliar processes. It's a smart relationship that's sparked up between the player, on one end of the screen poking away at various systems, and the game, and a novel perspective on the well-ploughed subject of an errant AI.

"I think it's maybe that games are one of the few places where you can properly explore that," says McKellan. "It's about being the one doing the actions. The idea that Sam, in the game, is self aware - or has just become self aware as the player takes control, with their humanness, their curiosities, and what they do as a player, all the familiar things you do as a player, will seem odd to the crew. It's this perfect agency."

That playful relationship between player and game positions Observation as one of those rare, most welcome of beasts; the psychological sci-fi game. I've only played 15 minutes of it, but I'm already fairly confident that, when they're chalking up some of the better games of this generation, Observation stands a good chance of joining Alien Isolation on my own personal list.