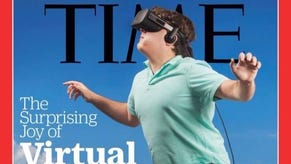

Oculus Rift: Step into the game, step out with two billion dollars

Like?

When Palmer Luckey and his colleagues set up their famous Kickstarter campaign back in 2012, they introduced Oculus Rift as "a new virtual reality (VR) headset designed specifically for video games that will change the way you think about gaming forever". Their convincing pitch raised $2.4m to build the first development kits, despite only asking for $250,000.

I was one of the 9522 people who bought into it, despite my personal scepticism about Kickstarter, a service that offers very little recourse to people who pledge money if things then go sour. For whatever reason, I had $300 that I could bear to part with at the time, I looked at the materials and judged that I would probably get the development kit I was being told would be manufactured, and it all worked out. When my kit turned up some months later and, after a bit of faffing around, I was able to walk around the train station in Half-Life 2 as though I was really there, I had no regrets.

Two years later, Palmer Luckey still talks about how his "foray into virtual reality was driven by a desire to enhance my gaming experience", even as he posts on Reddit explaining that Oculus has sold itself for $2bn to Facebook, a company whose main relationship with games is helping the people who make horrendous ones become extraordinarily rich. I still have no regrets, because I got what I wanted, but the whole episode will be a cautionary tale for anyone who thought Oculus' Kickstarter was more like a pinky-promise to put gaming at the centre of the next generation of virtual reality.

It turns out there are a lot of people for whom that was the case, and so the response has been pretty negative. Fans and backers, including high-profile ones like Markus Persson, have attacked Oculus' motives. "I understand that this happened because people with investments in the company saw big sacks of dollar bills," Persson replied on Reddit, echoing a lot of more colourfully worded responses declaring the deal a betrayal.

Two years ago this was a "headset designed specifically for gaming", but now Luckey says Oculus' original vision was "making virtual reality affordable and accessible, to allow everyone to experience the impossible", which it's easy to read as a convenient retrofit under the circumstances. To be fair to Luckey, he has never hidden his desire for VR to go beyond gaming, but it was easier to ignore that angle when Oculus was doing cool gamey stuff like hiring John Carmack than it is when he's just sold it to Facebook.

If there's a lesson here, perhaps it's the same one we should have taken on board last year when Microsoft attempted to replace the concept of game ownership with something infinitely less appealing: because of the way gaming companies are able to blur the lines between their consumer technology businesses and the games we love, we remain uniquely vulnerable to the emotional fallout from this kind of commercial shift. Facebook buying Oculus won't be the last time we feel like something that is ours is being taken away from us, so perhaps we need to be more sceptical and less trusting, even when the nice man with $75m of Series B funding from Andreessen Horowitz sounds like one of us.

Facebook's motives have raised fewer questions, at least, if only because they seem so obvious. "This is really a new communication platform," says Mark Zuckerberg. "By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life. Imagine sharing not just moments with your friends online, but entire experiences and adventures." And imagine all the personal data that Facebook can benefit from to assist in targeted advertising.

At least Zuckerberg insists that Oculus' plans for gaming will be unaffected, although when you start reading about the newly assembled wider Facebook VR vision - of sitting courtside at basketball games thousands of miles away and blah blah teachers and doctors or whatever - his statement that "Oculus already has big plans [for gaming] that won't be changing and we hope to accelerate" starts to feel less like reassurance and more like a desire to get this silly gaming stuff out of the way as quickly as possible. (The one thing that stands to protect gaming's role in VR, at least, is that game developers are uniquely positioned to create the spaces that exist on the other end of a visor.)

In the shorter term, Zuckerberg must hope this move will convince investors that Facebook will avoid getting caught out by another platform shift in the same way it missed the boat on mobile. (It has subsequently hauled itself onto the boat, but it was a huge distraction and even threatened to derail the company's IPO.) Either way, it's certainly worth a punt - and it's important to remember that while $2bn seems like more than that, it really isn't for a company like Facebook. Zuckerberg has purchased Oculus VR for the same amount of money he promised to give WhatsApp if that deal fell through.

In a way, for me that's the saddest part of this whole development: cash and stock swirling around Palo Alto - not even a particularly large amount of it by Silicon Valley standards - doesn't suddenly prove the transformative potential of VR, a technology that still hasn't resulted in a viable consumer device despite decades of attempts. And despite Luckey and Zuckerberg's protestations to the contrary, it's hard to imagine a deal with this surrounding complexity and uncertainty accelerating anything.

Speaking to the New York Times, Brian Blau from Gartner, an analyst who worked in VR many years ago, reflected on the old days thus: "Virtual reality had hip, hype and hope. Unfortunately the story is still the same today." Even as someone who has a first-gen Oculus development kit, I can't really argue with that, because until you can walk into a store and buy Rift - or Project Morpheus, or whatever Microsoft's cooking up - you're still only looking at potential. Perhaps that explains why Facebook got Oculus so cheap.

Oh well. Your move, MySpace.