One machine to rule them all: the triumph of Xbox 360

How Microsoft bridged three generations, and defined the modern console.

An era has ended: Microsoft is ceasing production of Xbox 360 after almost eleven years, 90 million sales and more games than I'd care to count, from sprawling Norse-inspired RPGs to borderline-pornographic Arkanoid clones. It leaves behind a console landscape once again dominated by Sony: PlayStation out in the lead while Xbox is a dogged pretender, a big black box with a weird (albeit now optional) controller. But for ten years Xbox 360 was the industry default, the machine that defined a console generation which lasted longer and reached more people than any that went before it. It did so by dint of three Dr Who-like transformations, reforming itself around a games industry that changed dramatically from PS2-era bro-dom to Wii-inspired mass entertainment and the downfall of both boxed games and the studios that made them.

It is pushing the bounds of credibility to say you could experience all of this on a single unit - the Red Ring of Death ensured that few launch consoles saw their third birthday, many fewer their 10th, and any left surviving today are probably too rare to risk turning on - but technically, they can still play the latest release of the evergreen gaming franchises of FIFA, Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto and now Minecraft. The Xbox 360 will still connect you to your friends list, and your Achievements, and your Netflix account. It'll do everything a modern console does, because it defined the modern console. And it did so by degrees.

It was built, in the first instance, as a traditional games console, in the template laid down by the PS2. Sony's great hit, the breathless hype for which had spurred Bill Gates to sign off on a Microsoft games console in the first place, was the model that Microsoft set out to beat. The original Xbox was saddled with a costly hard drive and a scattershot software lineup, and never overcame its late arrival on the market. It established a foothold but never stood a chance against Sony, and its creators knew the following generation had to go better.

Faced with the followup to the most successful games console in history, Microsoft played it straight and focused on the games. The Xbox 360 would launch alongside PS3, with a peculiar and derided name to disguise the fact it was only the second iteration. It would retain a PC-like architecture, and it would lean on Xbox Live and use the Controller S - the two unequivocal successes of the first Xbox. A hard drive would be an optional extra, as would a high-definition disc drive and a wireless connection. And it would have the best exclusive games that Microsoft's considerable financial resources could buy.

Microsoft threw all this into a 2005 launch expecting a head-to-head battle with PS3, which it would lose.Microsoft threw all this into a 2005 launch expecting a head-to-head battle with PS3, which it would lose. The PS2's dominance was so total, the PlayStation brand so established, that PS3's success was taken for granted; the best Microsoft could hope for was a spirited second place that would give it a seat in the living room. Instead, it managed to own it.

First, Sony blew it: the PS3 was late, too expensive, built around a bafflingly bespoke processor and connected to an under-featured and unreliable online network. Microsoft seized the opportunity and got the Xbox 360 out first, but only just: production started late and couldn't keep up with demand, making it maddeningly hard to buy at launch. I ordered mine in October and didn't receive it until the last day in January; others opted for the unloved and hard-drive-free Arcade version and bought the accessories separately to bring it up to spec.

But once you did finally get to open the big white box with the green-circle pattern and assemble the console from the brightly-coloured cable bags within, you had something quite exciting. In the grand tradition of console launches it didn't quite live up to its technical promises and the launch games weren't all that, but they still looked better, and the bulky, noisy hardware nevertheless felt new. The controller - imprecise D-pad aside - was a delight. It was comfortable to use, and wireless, and if you pressed the glowing logo in the middle you could instantly view your friends online, and send them messages, or join them in their game.

At a time when playing on PC still required timetabling and Teamspeak and, if you were unlucky, GameSpy, instant access to your friends in-game was a revelation. It came packaged with a new, narcotic distraction: Achievements. Described in abstract, these defied logic - a meaningless number that awarded nothing - but when encountered in-game they delivered a satisfying extra endorphin hit that started as serendipitous but soon became another reason to play. You didn't realise that flower pattern in Hexic was going to give you anything, but once it had, you were compelled to see what else was on offer and change your play style to reach it.

A thriving subculture blossomed almost immediately, the greatest delight of which remains the robust economy in indifferently-developed kid's games that gave up the full 1000G for only a weekend's play. The pinnacle of the form remains 2008's Avatar: The Last Airbender, which now exists as a sort of scarlet letter on the Xbox Live profile of anybody who ever got a bit too into Achievements: it gave up the full payout for a single combo which could be deployed the moment you were past the title screen. (So fast, I was assured as the review disc was passed at speed around the OXM office, the console didn't have time to warm up; the game held its second-hand value like no other tie-in, and is one of very few of the era to have made it to Games on Demand.)

Xbox Live also gave us Live Arcade, initially conceived as a home for 50MB time-killers but which went on to become a storefront for a new tier of game. Arcade Wednesday became a routine, mixing remade classics like Gauntlet with card games like Uno and oddities like Cloning Clyde, and the service became a thriving colony of the innovative and experimental, eventually going so far as opening the door to even the smallest developers via the Xbox Live Indie Games channel (that it then allowed it to swing closed again, while Apple, Valve and latterly Sony have not, is Xbox 360's great missed opportunity).

It was the lime-green boxes with the circular pattern that really took the attention back then, though. The yellow "only on Xbox 360" stamp kept cropping up on games that felt and looked new and exciting, that felt like they really were a new generation. After that wobbly launch lineup - looking back, only Condemned and perhaps Amped 3 merit prolonged attention - things picked up rapidly. The year after launch brought the gleeful experimentation of Dead Rising, the genre-defining shooting of Gears of War and the technicolour cultivation of Viva Pinata.

Simultaneously, Microsoft wooed the publishers of every game that anybody ever bought a PS2 for. The number one on the latter list, and the recipient of the biggest blank cheque, was GTA: Rockstar took millions to not only launch the fourth game on Xbox alongside PlayStation, but offer exclusive DLC. It was one of many. Tekken, Final Fantasy, Resident Evil, Ace Combat, Guitar Hero: anything that ever sold a PS2 came to Xbox 360, and each one added a few more people to your Friends list, a new leaderboard to inspect, a new set of Achievements to chase.

Microsoft's marketing money greased the wheels, but after a while the console's success - and PS3's malaise - did the job for it. Publishers openly admitted that they had to be on 360 to stand a chance in the North American market, ushering Assassin's Creed, Virtua Fighter and Devil May Cry onto Xbox when they'd previously been Sony exclusives; others, like Beautiful Katamari and Saints Row, became Xbox-only when the developers gave up on porting them to the idiosyncrasies of the Cell processor. Even Xbox 360's shocking reliability record couldn't hold it back.

The first Age of Xbox 360 peaked in 2007. The year that PS3 finally arrived in Europe was the year that Microsoft took its medicine for the Red Ring of Death, taking a billion-dollar hit to make all its reliability problems go away, and the year in which its investment in third-party exclusives paid off with a software lineup never beaten before or since. The year began with Lost Planet and continued with Crackdown, Bioshock, Forza 2, Halo 3 and Mass Effect, supported by quirkier fare like Lost Odyssey and Catan. The intoxicating multiplayer beta of Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare was exclusive to Xbox 360, and Sony's troublesome processor meant even multiplatform releases like Valve's Orange Box ran better on Xbox than PlayStation.

The Xbox 360 in 2007 was the zenith of the pure-games console, a high that will never come again. The dawn of the HD age was killing off the third-party exclusives; the development and marketing costs were so high that going single-platform wasn't financially sustainable, and even multiplatform wouldn't save Midway or THQ. The remaining exclusives were the weirdos or the waylaid; titles like Alan Wake, Too Human and Splinter Cell: Conviction; games out of time with the rise of the annualised mega-franchises.

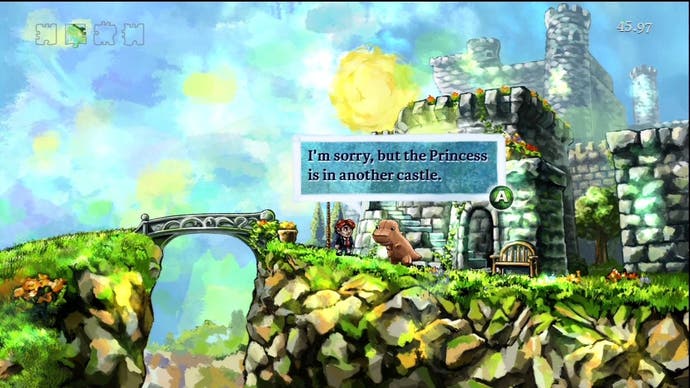

2008 was different. It was another massive year for lime-green boxes: GTA 4 finally arrived on next-gen, followed by Mirror's Edge, Dead Space, Fallout 3 and Rock Band, all of which took the boxed-game market to its high-water mark. It was big for the digital marketplace that would supplant it, too: the first Summer of Arcade delivered Braid, Castle Crashers and Geometry Wars 2, and Microsoft rolled out Xbox Live Community Games - a revolutionary initiative that brought independent creators into the closed console marketplace for the first time.

At the same time, Xbox went casual. That year's E3 mic-drop was Final Fantasy coming to Xbox, but the jaw-drop was watching Don Mattrick and the rest of the Microsoft top brass caper their way through You're In The Movies: a knockabout collection of minigames for the Vision Camera, an unloved peripheral previously only used by people who wanted to expose themselves while playing Uno.

This was another PS2 play, following in the footsteps, arm-waves and Journey singalongs of DDR, Eyetoy and Singstar. But the phenomenal success of the Wii had changed everything: the market wasn't just people who'd bought a PS2, but people who'd never bought a console before. Previously this would have necessitated a new hardware release, but with no obvious competition on the horizon and most of its consoles online, Microsoft didn't have to - it could just push out an update to re-tune the box it already had. Thus was born the New Xbox Experience, which junked the old blades system in favour of an infinitely-extending Rolodex fronted by smiling, wipe-clean Avatars: a cheery welcome for all those Wii owners who'd rocketed Nintendo to the top of the sales charts.

This was the dawning of the second age of Xbox 360, a have-it-all hybrid that saw Avatars and fitness instructors rubbing shoulders with Marcus Fenix and amnesiac Call of Duty protagonists. It was not uniformly welcomed by the players who'd signed up for the post-PS2 games machine, but Microsoft reckoned it could have it both ways. As long as E3 opened with Call of Duty, the thinking went, and closed with another big-name post-Sony signing - Final Fantasy, Tekken, Metal Gear - it could pack the interim with NeoGAF-enraging family nonsense and get away with it.

The thing was, it did get away with it, thus laying the groundwork for the doomed hubris of the Xbox One launch. The great contradiction of Avatars proved to be that having been built for those Wii-playing grandmothers, they were embraced most keenly by the "core" players, who then thwarted Microsoft's subsequent attempts to back away from digital dress-up. People were only too happy to invest in Gears of War-themed attire for their character, it turned out, and they're still spending on the Avatar Store even today - Microsoft having been forced to reintroduce Avatars after attempting to do away with them on Xbox One. Xbox Live Primetime, intended as a new programming strand, enjoyed a similar paradox: it didn't attract a huge casual audience, but the same people who chased Achievements were only too happy to play 1vs100. Even when it was trying to be cuddly, the Xbox 360 was a gamer's machine.

The age of Xbox 360 as everyman entertainer was cemented at E3 2009. Xbox 360 now had dedicated apps for Facebook, Twitter and Last.fm; the coveted third-party game slots went to Beatles Rock Band and Tony Hawk RIDE. The grand reveal promised to be truly transformational: forget motion controllers: you were the controller, and you'd not only be playing conspicuously Wii-derived sports games but interacting in carefully unspecified ways with virtual children. The future is coming, and it's coming to that box under your TV that you're going to play Black Ops on.

We know where this ended, of course, but that debut was genuinely exciting, and the whopping sales of that first Christmas proved it. 2011 was then a long, slow realisation that the future was not as bright as we'd hoped. The promise was Star Trek's holodeck, seasoned with Star Wars Force powers; the reality was Star Wars Kinect, a collection of minigames fitted into the handful of functions that the device could reliably support. There are some genuinely commendable Kinect games - Harmonix, Rare and Double Fine worked miracles - but it was too imprecise, needed too much space, and was rapidly swamped with the same half-baked shovelware that had failed to sell on Wii.

Kinect burned bright and surprisingly quickly; the peripherals craze was fading alongside it and even the Wii's incredible success was tapering off. Microsoft quietly switched its attentions to Xbox One, the purple-box section vanished from shops as quickly as it arrived, and the Xbox 360 entered its final, twilight form. Wii was out, iPhone - and more specifically, the iTunes Store - was in. The future wasn't quirky marionettes, but the Connected Entertainment Experience. That year's dashboard update made this clear: Avatars were swept off the front page, indie games were relegated again, and the top level was all about games and movies.

This was not a cherished decision, and it fostered the for-the-players rhetoric that Sony was able to deploy so successfully a year or two later, but it was a successful one. The world was going digital, and those Sky Movies and Netflix apps were getting regular and extended use. The Xbox 360's final form was the console as it is today: digital games, digital movies, digital music services, video chat: the blade-fronted box that was built for, and consumed an unprecedented volume of, boxed games transformed to the front-end for a thriving digital marketplace of everything you'd care to have on your TV.

Microsoft went ahead and designed the Xbox One to follow suit and actually, so did Sony: Netflix and music services were part of the PS4 from the beginning. That's just what consoles are now, although Sony grasped better than Microsoft that this is not something you should hang your launch campaign on, and it had already learned that you shouldn't include expensive hardware, either. Emboldened by its market position and knowing that it had once again spent a fortune on platform exclusives, Microsoft thought it could have it all (in one). The Xbox stumbled, and spectacularly, in those three months in the first half of 2013, and it has been chasing its old throne ever since.

Microsoft choked on its Kool-Aid come the end, seduced by its own phenomenal success, but the modern console is its own creation. The Xbox 360 was the connected box under your TV that gave you blockbuster games and arresting indie titles and on-demand video, that connected to your friends online. It brought indie developers onto consoles and championed digital distribution, and it gave us a controller that's become the world's default, a design used for everything from the Wii U to drone warfare.

The original plan was to follow the PS2 into a long and profitable retirement, but the world has moved on now: smartphones and tablets now occupy the kid's bedroom space that previously held a PS2 slim, and Microsoft's commendable decision to bring backwards compatibility to Xbox One means that the 360's vast software library no longer needs the console that spawned it. After almost eleven years, the green ring of light is going dark, on an industry that's changed out of all recognition: that it kept up for so long and delivered so much is an unprecedented achievement. Goodbye, Xbox 360. You'll be missed.