Passively Multiplayer Online Game

Putting the mines in data-mining?

A trawl through the comments section of the missions page suggests that the game's community has a slight tendency towards the sharp retort, which can presumably be rather painful when you've just stitched together a trail of your favourite things to show people. "It's still pretty friendly, but comments are always where people are the most out of character," says Gough, who admits that trying to keep PMOG pleasant is one of the team's main objectives. "We encourage a degree of rivalry and revenge within the game itself, but that's not allowed to spill over into outright rude behaviour. However, it's been easy to identify those people who have a positive effect on our community, and we give them the tools to keep things that way."

Beyond the slight in-fighting, PMOG has been met with a fair share of understandable suspicion due to the web-tracking at its core, with some alleging that the game is little more than self-inflicted spyware, and playing it not far removed from knowingly giving yourself tetanus. The game's privacy policy states that while PMOG tracks URLs, it does not track secure sites, or monitor what you type into web windows. The use of your data appears largely limited to sharing it with contractors working on the game itself. And while PMOG "may disclose player data in limited circumstances if we believe in good faith that doing so would: comply with legal process, prevent fraud or imminent harm, and/or help ensure the integrity of PMOG," this presumably has more to do with the war on terror than giving Jeff Bezos and the Russian mafia a direct insight into your shopping predilections and bank account numbers.

"We remember the early 'sponsored browsing' tools and we don't want to replicate that," adds Gough, who's clearly used to discussing privacy issues. "One of the earliest versions of PMOG was built for the BBC so we're acutely aware of the implications of web tracking. There's already a number of extensions that track where you go on the web, like StumbleUpon and the Google Toolbar, and neither of those companies have sold data for profit, so I think the standard is already set. We only store data that makes the game fun. On top of that we have a number of privacy settings for players, including the ability to delete all of your data."

Nor are PMOG's creators planning on funding the game by selling your data to third-parties - at least, not any time soon. "At this early stage we're looking at advertising, but now that we have the initial gameplay nailed down, I think it'll be exciting to look at other ways of making money from a passive game such as PMOG," says Gough. "Since we're a mix of web, games and social networking, we have a broad range of business models to consider."

That may sound ominous, but such fears aren't keeping people away. Gough describes the player base of PMOG as "moderately large," and also adds that a lot of people are sticking with the game over time.

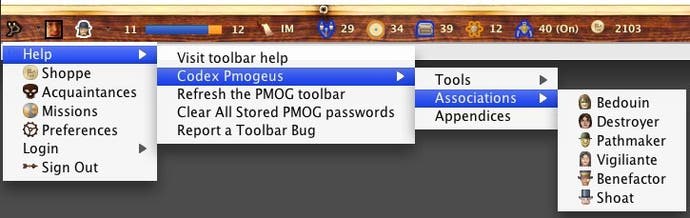

Inevitably, passive gaming may be too strange and inconsequential for many, and might even be a little mean-spirited at times for others. But overall, PMOG's a testament to the way that game mechanics can subtly alter the way you approach everyday life, whether it's in-game items revealing a secret landscape within familiar web-pages, or user-generated missions bringing back the early days of exploration that categorised internet activity before the rise of Google. And although you rarely directly interact with other players, you'll still see their footsteps everywhere, in the missions they've left, the portals they've constructed, and the mines and loot they've laid in their wake.

Ultimately, then, PMOG is the internet, and while it may share many of its worst traits, it also shares some of its best, too. At the very least, the game provides a new perspective on things: familiarity may have tamed the web somewhat, but by giving its players an insight into one another's online lives, PMOG is already helping to bring back a little of its original strangeness.