Pixel Poetry review

Another video games documentary that doesn't talk about video games.

Games documentaries, it seems, are much like the proverbial buses. You wait years for one, and then loads turn up at once. Having had the doors kicked in by the likes of King of Kong and Indie Game: The Movie, we're now experiencing something of a glut of factual films about gaming, all seemingly intent on proving the artistic worth of the medium.

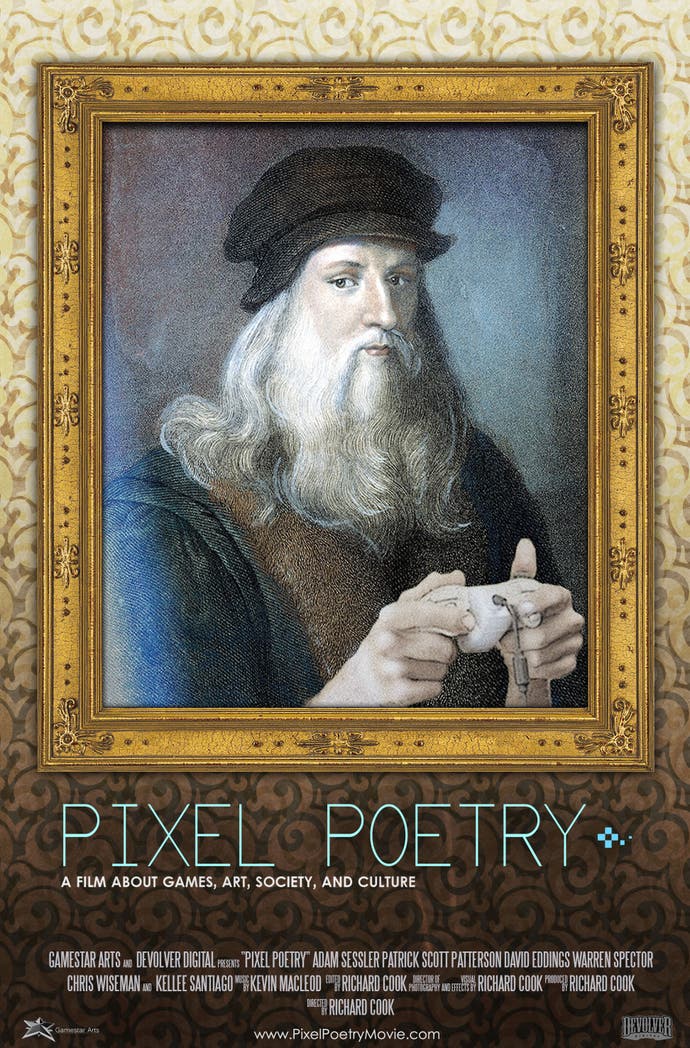

Pixel Poetry is the latest, and it would seem to have several advantages. Not least, distribution from Devolver Film, the video arm of games publisher Devolver Digital. From Hotline Miami and Gods Will Be Watching to Titan Souls and Hatoful Boyfriend, Devolver is to games as Warp Records is to music, curating a catalogue of interesting, genre-bending projects with an eye to the experimental and ingenious, while also branching out into other media like film.

The participants, too, promise great things from Pixel Poetry. Warren Spector has long been an outspoken commentator on both the value and potential of games. Kellee Santiago, formerly of thatgamecompany, helped to bring games like Flower and Journey to PlayStation, thus dragging the "games as art" debate into the console spotlight. Similarly, Jan Willem Nijman of Vlambeer and Ian Dallas of Giant Sparrow are both freshly minted stars of the indie scene who can speak from personal experience. The more corporate side of the equation is covered by EA's Gordon Walton and Feargus Urqhart from Obsidian.

Sadly, as with the boldly titled but lamentably shallow Video Games: The Movie, the same argument is framed and reframed over and over, but tangible, useful insight remains frustratingly out of reach.

Pixel Poetry does, at least, have some notable improvements over the saggy Video Games: The Movie. For one, it's much more compact and focused. There's no meandering history lesson through the evolution of interactive entertainment here. Rather than stretching itself thin to feature length, Pixel Poetry runs just over one hour, minus credits.

It's also much more coherently put together, with lines of argument that are followed through, and segues between topics that make sense. Both films share a weakness for using highbrow quotations as punctuation marks - in this case, Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln are among the luminaries to be invoked - but Pixel Poetry manages to present itself with enough dignity and grace that the quotes don't feel like they're propping up a sophomoric argument.

The argument may be better presented here, but it is still the same old f***ing argument: why games are art. It's hard not to sympathise with this ongoing search for wider cultural validation but, despite its superior presentation and more insightful talking heads, Pixel Poetry still doesn't advance the discussion in any meaningful way.

So we get the expected trawl through questions of artistic legitimacy, along with answers that supposedly show how games measure up to this bar. The obligatory tabloid controversies - games addiction and gaming violence - are dragged up again, only to be shot down with a few well-phrased rebuttals.

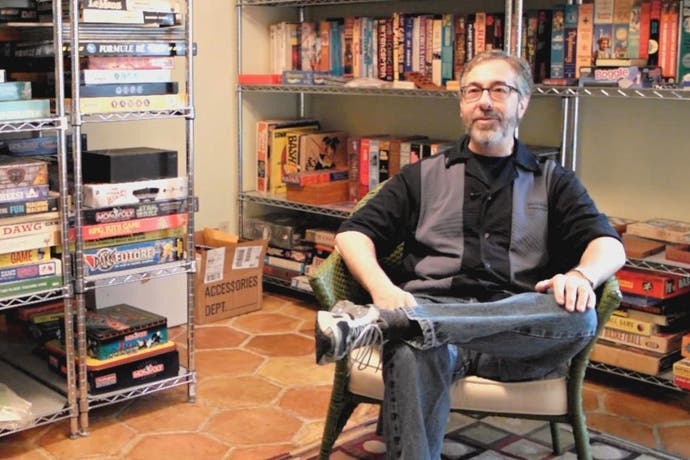

Former G4 host Adam Sessler is particularly insightful, pointing out that in centuries past the Vatican tried to suppress opera, fearing its secular nature and cultural popularity. His explanation - that games are just the latest medium to require a cultural vocabulary that the gatekeepers of mainstream power lack and therefore fear - is astute and compelling, so it's not that there are any real complaints about the way these topics are covered, more that in 2014 they really don't need any more coverage. It's time to move on.

Pixel Poetry, while stylishly made, ultimately fails to engage with its own argument. Instead, as with so many other attempts to cover gaming on film, it ends up repeating its thesis - games are art - in lieu providing any tangible evidence in support. The individual games are reduced to moving wallpaper, never directly addressed but called into service to provide generic accompaniment to the opinions being shared.

That's especially frustrating in this instance, since many of the interview subjects could easily provide that very insight. It makes no sense to have Kellee Santiago on camera, and to have numerous clips from Journey, yet never connect the two. Rather than asking Santiago to extrapolate on broad, well-trodden arguments, why wouldn't you instead ask her to actually talk specifically about Journey, about the creative processes, the thoughts and intentions that went into its construction, the emotional responses designer Jenova Chen was trying to evoke? I've seen Santiago and Chen talk on this very subject at press events, and nobody having seen them could deny that they were listening to artists talking about their art. It's an open goal, and Pixel Poetry doesn't even take a swing at it.

This is the hurdle documentary makers need to overcome, this inexplicable aversion to having game designers simply talk about their art, and explaining how those designers are able to use the cold clay of zeroes and ones to make us feel joy, sadness, guilt or fear. Despite having the balls to portray Da Vinci with a joypad on its poster, Pixel Poetry never dares to venture into the chewy core of game design where the art actually happens.

What's the point of showing Super Mario Bros in a documentary about the art of games, if you're not going to explain what makes it so wonderful, so timeless? This is where the argument will be won, and we can't shy away from attaching specifics to it. Enough with the generalities that try to make a coherent case for everything from Candy Crush to Call of Duty. If we're to convince the wider world that games deserve to be taken seriously, then we need to talk about them in a serious and specific way.

All the expected games are prominently included in Pixel Poetry, yet none are explored in terms of their artfulness. The playful clockwork precision of Miyamoto's design, the nursery rhyme dread of Limbo, the acidic romantic critique of Braid, the subtle emotional crescendo of Ueda's Shadow of the Colossus, the nerve-jangling moral role play of Papers, Please - all are reduced to montage wallpaper rather than in-depth examples that might actually add some muscle to the case for games as an artform. It's a waste.

Maybe the viewer is assumed to understand their significance, in which case Pixel Poetry is just another film made by gamers, for gamers, safely preaching to the long-since converted. Or maybe there's a worry that the non-gaming audience might turn off if we get too deep into the guts of how games are made. Yet what does that lack of confidence say about our faith in the medium?

There's beauty in the primal call and response of a well-crafted gameplay loop that packs an emotional punch, just as surely as there's beauty in the well-turned phrase of a sonnet, so why not explain that using identifiable examples? If Sessler's point about the cultural vocabulary of gaming acting as a barrier to wider understanding is true, then any film tackling games as a serious subject must first provide a translation - not in broad, vague terms, but by breaking down what makes games special into the equivalent verbs and adjectives, and getting the artists in question to explain why they used them.

Pixel Poetry has its moments of insight, but it still speaks the language of games to an audience already fluent. It's better than Video Games: The Movie in a lot of ways, but also falls into the exact same trap of leaving the viewers who most need to be convinced out in the cold, no closer to understanding games than before.