Retrospective: Planescape Torment

What can change the nature of a fan?

Take the introduction of Ignus, a pyromaniac wizard, channel to the realm of fire and former student of the cruelest incarnation of the Nameless One, who can be persuaded, gingerly, to join your party. You first encounter him in a bar named, eponymously, The Smouldering Corpse. His sprite hangs in the middle of the foyer, impressively flaming, but not really enlightening. It's in the text that you interact with him, seeing him hissing with idiot malice and insanity from his decades of agonising imprisonment. The game even gives you the option to sacrifice parts of yourself to his flames in return for permanent weakness, increasing disability, and access to his unique spellbook.

Whilst talking about Ignus, it's worth noting the number of purely optional, totally bizarre and entirely bypassable party members. The entire game can be completed without comrades (indeed, for a speed run it's pretty much necessary) and half the party members are extremely difficult to access. Save for Ignus and the puzzle of extinguishing his eternal flames, there's the Nordom the Modron, a corrupted minion of the computer-like realm of logic Mechanus. You can only encounter him by buying a puzzle box from a particularly strange store, which opens up into a whole procedurally-generated dungeon floating in limbo, and it's both one of the most challenging parts of the game and a bluntly comic parody of D&D and role-playing computer games altogether (the puzzle box itself can, incidentally be swapped later for the most powerful evil weapon in the game, as long as you don't mind dooming the universe to eternal war). Then there's Vhailor (an empty suit of armour motivated only by justice) who's walled-up underground somewhere, the intellectual succubus Fall-From-Grace, and the half-demon thief Annah.

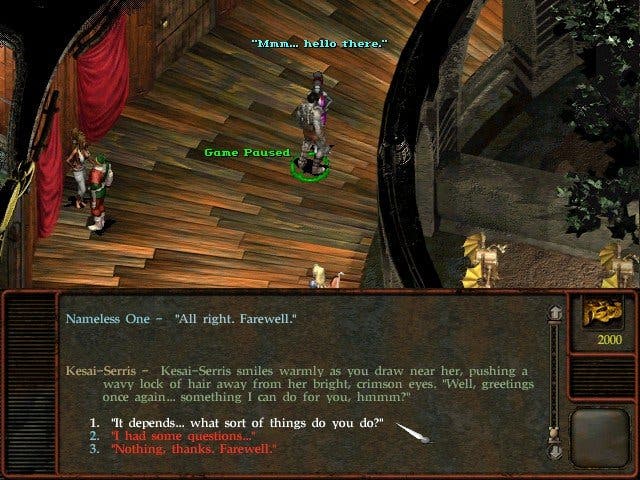

The party members you do take on board are developed almost entirely through dialogue, which allows you to unlock more of their story the longer you play with them. Your first potential party member, the endlessly gabbling Morte, is a cheeky flying skull whose bite is as bad as his bark. His levelling up is done partly by learning horrible new insults. Meanwhile, the ancient Githzerai Dak'kon is a particularly strange example - interacting with a puzzle item he gives you results in more of his story being revealed, new combat buffs for your character and more dialogue choices with him, which unlock more abilities and a greater story about the planes themselves and his race in particular, a story that's ambiguous and leaves him both a hero and a villain (and one of your former incarnations either a villain or misanthropically pragmatic).

There's even characters mentioned in passing who demand stories of their own - a former companion of yours, the blind archer, whose zombie you find, or the Lady of Pain herself (the godlike overlord of Sigil) whose name cannot be mentioned (but about whom theories abound that she's in fact six squirrels with a headress, robe and ring of levitation). It's emphasised throughout the game that you are, and always have been, doom for those lost souls who tread your path, and that all these who walk with you are fated to die, soon.

Planescape's deliberate weirdness doesn't finish with the characters, or the world. The contrary design decisions continue throughout the game. The language of the game is close to Chaucer or Iain Banks' Feersum Enjinn, relying heavily on old east London "cant", a mixture of the lingo used by cony-catchers, pick-pockets and bawdy-baskets. A typical sentence might be, "It's a right berk who thinks a blood or cutter will spill the chant without some jink." There are almost no swords, despite you starting as a fighter character (the Nameless One can shift classes between thief, fighter and mage repeatedly as he remembers his previous lives). Rats can and do beat you up, especially in large numbers, though your main character can never die.