Playing Moby-Dick - the card game?

Sing out for new stars.

Calenture is a phenomenal word. It can only be medical, right? Is it medical - or maybe nautical?

In fact, it's both. Calenture: a delirium occurring from heat stroke or fever, in which a stricken sailor pictures the sea as grassy meadows and wishes to dive overboard onto them. Imagine that! A fundamental confusion between land and water. If you ever want to get a sense of how long whalers used to spend on their voyages back in the bad old days when leviathans lit the world with the lamps fuelled by their noble bulk, well, there's your answer. Sufficient time - and sufficient stop-overs in the tropics - for calenture to take hold. Sufficient time to leave you desperate to lie down on the bristling wilds of the ocean blue and nap in the bosom of the briney deep.

Calenture does not come up in Moby-Dick as far as I can remember, although, granted, it's a big book and I'm very forgetful these days. (For example: I'd forgotten the hyphen.) It's definitely the kind of thing Herman Melville would have loved, though: the sea's impact on the mind writ arrestingly large, the sea as status effect. Happily, for the flow of this article, it's the kind of thing that would work pretty well in Moby-Dick: the Card Game, too. I can imagine drawing Calenture from the sea deck and thinking: Oh hell. There goes another one.

I've wanted to play King Post's card game interpretation of Moby-Dick for a while, partly because Moby-Dick is just about my favourite book in the world, give or take Carter Beats the Devil, but largely because I was fascinated to see how such a maddening, maddened, uncontrollable novel could fit into a game played neatly with three special decks of cards, a few counters, and some dice. After all, it barely fits into the word novel. Sure enough, when I finally got the box in the mail, I shook the contents out onto my desk and felt distinctly disappointed. It formed a smart little pile. It all looked too tidy.

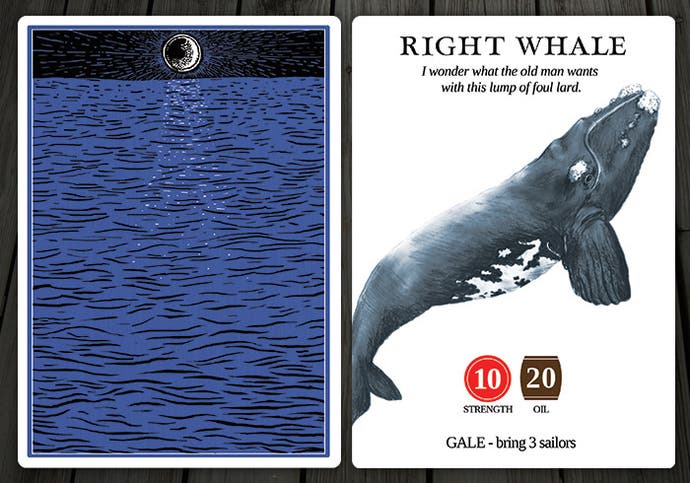

And on the surface, at least, the game is fairly tidy. It's about building a hand, in essence, and drafting a crew of sailors strong enough to give you a decent chance at surviving an encounter with Moby Dick (no hyphen) when he eventually appears. You start with just three tars, drawn at random from the sailor deck, and then you play through the game, taking turns to deal cards from the sea deck, which tell you how your tale unfolds. You stop off at islands and stumble across blobs of glorious ambergris, and occasionally you get to fight a whale.

When this happens, you choose how many sailors you're going to pit against the beast and then you lower for it. If you win - the fight plays out by rolling dice and dealing with attacks from the whale deck - you gain more of the oil you need to buy additional sailors, all of which come with their own quirks and skills. Eventually, you reach the point where Moby Dick can be summoned, and then everyone has at him at once - or rather he has at all of you. The last player standing wins - even if it doesn't really feel like winning. It doesn't really feel like standing, actually. For one red cherry ere we die!

This is all very nice and straightforward. The only problem is that Moby-Dick, the novel, is neither of those things. For a lot of the time, it isn't really about hunting whales, either. Moby-Dick's one of those books that seems to be fundamentally concerned with testing the boundaries of what a book can be. Maybe that's why it tanked so hard on its initial release.

Indeed. Herman Melville, one of the most famous writers in history, was once a best-selling author as well. And his best-sellers, inevitably, are a bunch of books nobody's ever heard of. Is there a lesson here? Anyway, I've read Typee and Omoo and a few of his other early crowd-pleasers, but they are not Moby-Dick, and in truth, I read them because you can only read Moby-Dick for the first time once. From rowdy acclaim to difficult brilliance: in some ways, Melville was a spiritual ancestor to the game developer who leaves behind the bland envelopment of the blockbuster studio - granted, I bet it isn't that bland when you're on the inside - for the hardscrabble life of the fiercely specialised Indie.

What a designer he would have been, too. I love Melville's aggrandising imagination, which, back at the start of his career, earned him a handy notoriety as the man who had lived amongst cannibals. (In reality, he had most likely spent around a fortnight with them, and they probably weren't cannibals anyway.) I love his unwillingness to allow his books' mysteries to be fully unravelled: I love that the whale in Moby-Dick is a symbol of many things, but that many of these things conflict with one another - and besides, it is also, unavoidably, a whale too. I love that Melville seems to resist the easy coherence - closure is the grim banality we use these days - that allows you to shut a book and then file it away forever. Puzzle solved. Next.

And I'll even admit this: somewhere along the line, I think I crossed over. I live in my current house because it reminded me of the house in Melville's I and My Chimney (I wish he had mentioned the leaky roof), and I send my daughter off to sleep each night by reading her the Moby-Dick board book and acting out the voices with a little too much enthusiasm. (I wish they did a board book of The Confidence Man, but you can't win them all.)

Mostly, though, I can control myself, and these days I think I love Melville in general and Moby-Dick in particular simply for that boundless ambition regarding what books can do. Melville's sea is a sea of ideas, of etymologies, of references, of threats, and of asides. Who needs closure when you're friends with the pale usher? Then, just when you expect the narrative to focus in, it fragments utterly, as only a certain kind of book's narrative really can.

So yes, how to fit so much splintered wonder into a card game?

A lot of it inevitably just doesn't fit. Sat in a meeting room with Tom Bramwell, playing a few rounds of King Post's game, I was not moved to think of the metaphysics of whaling very much, or the lurking evil of sheer whiteness, or even the fact that it was a mutual joint-stock world, in all meridians, and that us cannibals must help these Christians. That's not just because Tom insisted on humming the Jaws theme throughout, either. Melville's book can appear wonderfully chaotic in its endless allusions and tangents. The card game has to pick its battles - but at least the battles it picks, it tends to win.

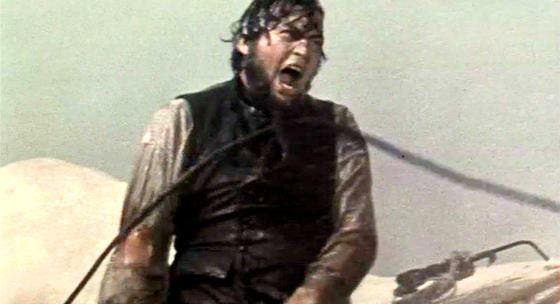

Crucially, it nails the wildness of the sea and the wildness of nature. The sea deck's always willing to do you a wrong-un, and it's also willing to throw deadly opportunity your way in the shape of those whales you can hunt as you tool up to tackle the big one himself. There are legendary whales in the deck, which come with their own special forms of brutality, but even the standard whales will really take it out of you. You roll dice and tot up your sailor strength to get fast to a whale - to land your harpoon in its flesh and become attached - and then you roll dice to finally finish it off, all the while fending off the whale's own attacks as it smashes you and rams you and knocks your sailors into the deep. Understandable behaviour, if you ask me.

This hectic business used to be called the Nantucket Sleighride, but only because the people of Nantucket had never found themselves chained to the back of a rampaging freight train while people on the train pelted them with spanners. I suspect it's nothing like a sleighride at all, in fact, and the card game manages to bring that to the surface, while also reminding you - and I had never really noticed this - that Moby-Dick's ultimately concerned with a bunch of people who do something terrifying for a living.

These battles are nothing compared to the final confrontation, however - and this, too, is handled with real elegance and wit. As you play Moby-Dick, you occasionally draw chapter cards from the sea deck. These serve to give the game a rather literary bent, but also lay on status effects - or more accurately the room feelings from Roguelikes - that remain in play until the next chapter card is drawn. When you reach the agreed number of chapter cards - I've played for a total of five chapters, by and large, which gives you about an hour of hunting - you can summon Moby Dick the next time you draw a Moby Dick card - a sinister white fellow, this one, with a menacing quote about what a nightmare that whale truly was written on one face.

Simple as this trick is, these cards really conjure menace, and they clear the decks for a final battle which you cannot actually win. Spoilers: Ahab and company don't get the whale, although Melville's enduringly vague about the whole thing. Accordingly, the fight against Moby Dick in the card game sees you competing with other players to merely survive for as long as possible. You can't attack, you can only defend. It isn't going to end well.

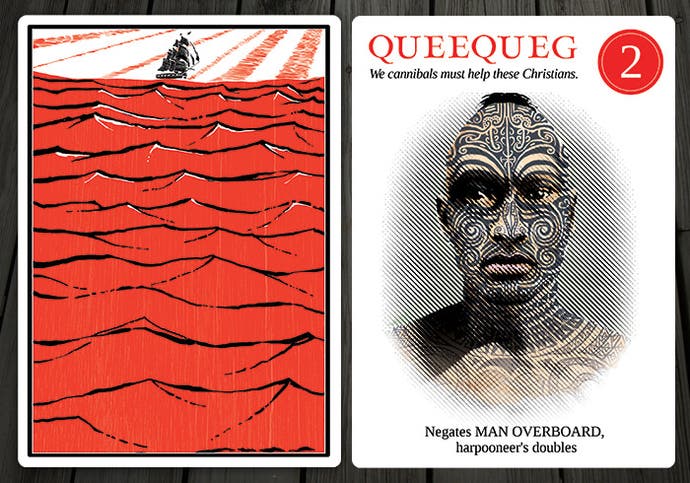

Finally, and most surprisingly, the card game captures much of the antic humanity squashed into Moby-Dick, and it does this by turning its characters into something people playing a game will actually pay attention to: modifiers. You'll learn to cherish members of your crew not through their brief descriptions or the illustrations on their cards, but through their perks and anti-perks. The way that Elijah is a cursed sailor, for example, who must be kept in your boat whenever you lower for a whale, even though he drags your attack power down. The way that The Handsome Sailor allows you to re-roll any dice roll, or that Queequeg negates Man Overboard cards.

The humanity! Oh, the humanity! At his worst as a writer - and Melville's genius is the kind where I would argue he is always chummily within reach of his worst at any moment - you get Melville the maxim-minter, ready to codify the world and lapse into drafty generalities. At his best, though, he is uncommonly brilliant at bringing his time to life with humour and with sheer human warmth - often before twisting what he has seen in sinister directions. The best bits in Moby-Dick are often when the metaphysics blurs out and you just get the crew, muttering on the forecastle - do people stand on that bit? - fretting and imploring, accidentally clasping each others palms as they pulp whatever it is that gets pulped when you're turning whales into oil.

Case in point: Bulkington. Bulkington's a sailor who makes a big entrance about 15 pages into Moby-Dick, and immediately seems destined for greatness. In chapter three, a bunch of whaling buddies come bounding into the Spouter Inn causing all kinds of mayhem, but one of them, Bulkington, stands a little apart. He's a huge, rugged, handsome man with tanned skin and bright white teeth and 'a chest like a coffer dam". He has noble shoulders, which is quite a thing to have, and even better, in his eyes float "some reminiscences that did not seem to give him much joy." This early on in a book this large, an entrance like Bulkington's suggests a character you're going to get to know a bit. Bulkington has promise. But then, he pretty much disappears, resurfacing briefly 20 chapters later so we can read about his startling moral stature, before he finally dives deep again for good.

What was Melville playing at? Theories abound. Some think Bulkington's there to hold up a mirror to mad, bad Captain Ahab - to balance his demonic presence with something a little more serene. Others suspect he's a reference to Hercules or to Melville's enduring love of Turner paintings, although I've never quite understood the thinking behind the whole Turner angle. My favourite theory is that Bulkington is a ghost from an earlier draft of the book - possibly even a literary bug or glitch of sorts - left to wander chapters three and 23 forever, his greater significance locked away in another dimension, an earlier plan, or otherwise consigned to the wastebasket.

Bulkington's my favourite character in Moby-Dick, and he's in the card game, too, where he comes with the ability to negate Charge, The Tail or Bite - at the cost of his life. He pinged back and forth between my crew and Tom's crew several times as we played before finally drowning with me when Tom won. As I stacked the cards and shoved them back into their box, I realised that the designers had given Bulkington a familiar face - a young Herman Melville, painted around 1846 by the gloriously named Asa Twitchell.

Perhaps the card game is another ghost in the great novel: devious-cruising, loose not fast, never entirely crossing paths. The mystery of Moby-Dick certainly deepened over the hour or so we played, which feels like the ultimate mark of success. And when it was over, I sat there for a minute and pondered my role in Bulkington's strange fate, while Tom eventually got tired of the Jaws theme and headed back to his desk.

And nobody - nobody! - got closure.