Hunky Dads & Voxel Flags - Video Games and Our Queer Future

How games can help us imagine a queerer world.

Hello! All this week Eurogamer is celebrating Pride with a series of stories examining the confluence of LGBT+ communities and play in its many different forms, from video games and tabletop games through to live-action role-play. Next up, Sharang examines the way players are using video games to explore the potential of a queerer future.

When we talk about videogames as "escapism", we tend to focus on provenance: we're escaping from the humdrum of our jobs, our obligations, the petty horrors that fill modern life. Seldom do we focus on destination. Where are we escaping to? Is it actually a better world than the one we're attempting to leave behind? Videogames can offer us worlds we might like to live in; can they offer us worlds we can live in? And particularly for queer people, what does that world look like?

In Tracing Utopia, a documentary that premiered in the International Film Festival Rotterdam 2021, filmmakers Nick Tyson and Catarina de Sousa question a group of queer teenagers about their vision of a queer utopia. The responses are varied. Better access to mental healthcare, queer history in schools, desegregated bathrooms... "My idea of a perfect world is a forest," chimes in one teen.

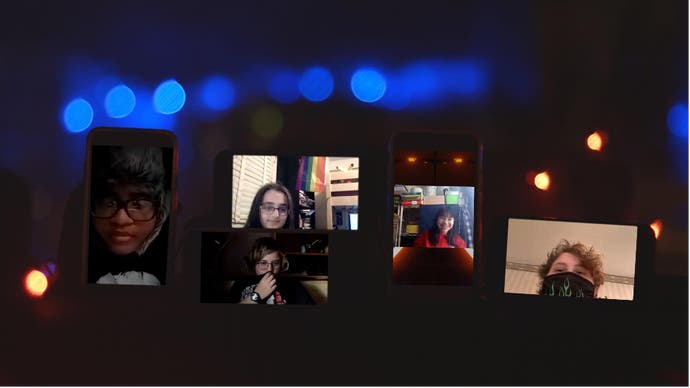

The teens' sentiments strike a particular chord since Tyson and de Sousa set much of the film within Minecraft, a game famed for allowing players to build, well, a "perfect" world of their own, block by block. The filmmakers superimpose videoconference footage directly onto the teens' private game server, juxtaposing the meatspace-the real, the tangible, the present-alongside the digital space-the potential, the virtual, the possible future.

"Queerness exists for us as an ideality," writes José Esteban Muñoz in his seminal book Cruising Utopía, "that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future...Queerness is essentially about the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world." And what a potentiality, what a possibility the teens imagine! Within the videogame, the teenagers can express whatever style, whatever gendered or non-gendered presentation of themselves they like ("Online, it's easier to be yourself," one of them states). They are free from the judgement and misunderstandings they face from their family and acquaintances. Displays that might not be safe outside of their real-world rooms ("Here's my 'tranny flaggy'," one trans teen proudly states, pointing their camera to their bedroom wall) are imbued into the very architecture of their Minecraft utopia, pride flags, banners, and rainbows ubiquitously built into their voxelated world. There are cats everywhere. In some sense, Tyson and Catarina tell us, the teens have built in Minecraft the queer paradise they envision for the future.

Building worlds, be they better "eutopias", worse "dystopias", or just different (sometimes referred to as "allotopias"), is a fundamental constituent of games. Even more abstract games like Checkers or Go involve the creation of a space within which ordinary rules are suspended and game rules dominate. Scholars refer to this concept as the "magic circle". To many of the educators at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, where I currently serve as Game Artist in Residence, world-building is the lens through which to view games. Adjacent to the fictional worlds of film and television, which to a large degree form the core of the MoMI's scholarly interest, game spaces are another way for people to navigate stories. And "navigable spaces", Janet Murray contends in Hamlet on the Holodeck, are one of the features that makes games games, that differentiates them from other forms of media.

Our ability to shape and gain meaning from these spaces-these worlds-is what interests Tyson and de Sousa, and what the teens in Tracing Utopia, consciously or not, seem to respond to. Minecraft allows the teens to very literally build another world, one free of judgement, queerphobia, and stifling tradition. "While play spaces are generally fantasy spaces," writes Mary Flanagan in Critical Play, "players often experience real stakes when inside them." The teens are under no delusion that their virtual play space reflects the real world; yet, their experience within that space is potent. Playing in a utopia allows the teens-allows people-to taste what that utopia feels like, to bring the utopia closer to reality.

"While play spaces are generally fantasy spaces," writes Mary Flanagan in Critical Play, "players often experience real stakes when inside them."

Such explanations demonstrate the importance of games like the highly lauded Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator by Game Grumps. Dream Daddy casts you in the role of a single father moving to new neighborhood with your daughter. The game focusses on two major plotlines: your changing relationship with your daughter and your dating life with the various handsome, eligible fathers who live in your quiet cul-de-sac. While conflict and drama abound in Dream Daddy, the world the developers build can be considered very much a queer utopia. Homophobia, transphobia, and the like are notably absent. Gay and trans identities are accepted without question. Your skin colour and body shape matter not a whit to the hunky dads that romantically pursue you. Laura Hudson at Wired magazine notes that the game has even attained a remarkable following from gamers outside the LGBTQIA community. She quotes Leighton Gray, one of Dream Daddy's creators: "I've never seen so many people who are straight or who never play videogames play it."

Acceptability from an oppressive majority is hardly the hallmark of good art, of course. Some argue that this rapid, widespread acceptance of Dream Daddy outside the queer community might portend that the game fails queerness itself, that in its attempts at mainstream palatability, it loses its essential queerness. Braidon Schaufert discusses many such critiques of Dream Daddy's essential optimism in his Game Studies paper Daddy's Play: Subversion and Normativity in Dream Daddy's Queer World. "Optimism, in the context of queer lives, serves those who are privileged by homonormativity, because they can disengage from the realities of social problems and avoid negativity," he writes, continuing, "the optimism in the game flattens differences and ignores social realities that inflect the lives of queer, racialized, or transgender people." This sentiment is not uncommon. Speaking about games more generally, scholars Tanja Sihvonen and Jaako Stenros summarize the thoughts of numerous game theorists when they write, "[Take] the removal of oppression, homophobia, and transphobia from the gameworld. While it is meant well, much of queer and trans history becomes nonsensical if such structures are removed during the design process."

This sort of argument has appeared time and time again regarding queer media. Recent films such as Call Me By Your Name and Love, Simon have faced similar critique. The world is too nice. Too mainstream. Too hetero. While compelling and valid, such arguments are nevertheless limiting. The richness of queer experience can make room both for art that grapples with the history of queer adversity and art that revels in saccharine "normalcy". There is no singular way to understand queerness-that would be a contradiction in terms, a normalizing of that which by definition is a rejection of the normalized. Media that delve into our struggles as queer people and the history of violence against us have a critical role in our consciousness; so do those that posit happy utopias. Evan Lambert, in the now-defunct website We Are Flagrant, rejoices in the fact that thoroughly mainstream and optimistic films like Love, Simon offers queer teens "the same lies about love that thrilled their straight peers since the advent of the first modern rom-com" and "a road map, albeit a fictional one, to happiness." Such road-maps need not be concrete, need not even be accurate; the point is for them to exist. As game designer Mattie Brice told Nina St Pierre for Bitch Media: "By performing utopia...the body gains memory of it". Playing at utopias makes us think about how to build these utopias.

Perhaps queer utopias are all lies. Perhaps we can never attain one, and attempting to do so amounts to futility incarnate. But "lies" are simply another way of saying "stories". To the teens in Tracing Utopia, to gamers everywhere who explore, build, and play within fictional queer joy, such stories hold power. We see that in how the teens talk to Tyson and de Sousa:

"Things can change over time."

"Nothing has to be the same."

"I started researching how to build a better world."