Twine Games and the Trans People Who Love Them

Exploring how trans developers use interactive fiction.

Hello! All this week Eurogamer has been celebrating Pride with a series of stories examining the confluence of LGBT+ communities and play in its many different forms, from video games and tabletop games through to live-action role-play. Today, for the last of this year's Pride Week features, Eli Cugini explores the way trans creators have embraced Twine interactive fiction.

Last summer, I read a tweet telling me that Ronald Reagan can use they/them pronouns for you while ordering you to do war crimes in the new Call of Duty. This was, of course, a boon for me, seeing as the only thing keeping me from a £59.99-with-microtransactions, time-to-shoot-some-commies FPS was the lack of gender-neutral options.

Jokes aside, as a gay who has played a lot of games by straight people, including straight people who think they can write convincing lesbians, I've been thinking a lot about this kind of surface-level representation. Honestly, Cyberpunk and COD can put in cosmetic trans options if they like, but I don't really care. If I want to play a triple-A game in a trans or lesbianiacal fashion, I can probably make up a better way to do so than the developers can.

What I really care about is what queer and trans people can do with games, which is why I've been spending a lot of time on Twine. I came across Twine in 2020, eleven years after its launch and six or seven years after it was covered by every national newspaper in the US. (Being a 16-year-old Brit with a janky laptop during Twine's heyday, I somewhat missed the bus.) If you don't know what Twine is, it's free, open-source software for creating interactive fiction that doesn't require knowledge of a programming language. You might have heard of the Twine games Depression Quest or The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo, or watched Black Mirror's movie-length episode Bandersnatch, which was storyboarded in Twine. I've found most of my favourite Twine games on itch.io and the Electronic Literature Collection.

Twine is also one of the few places in gaming where trans people have a strong, visible presence: Porpentine, Anna Anthropy, and a host of other trans developers - particularly trans women - have gained acclaim and local prominence for their creations in Twine. This is partly due to Twine's accessibility to people without a lot of money or formal coding training, and partly because of how trans art works: Twine, and interactive fiction more generally, work really well for telling trans stories.

I got into IF as a teenager through the free app port of Frotz, an interpreter for old Infocom games, which I presumably downloaded because 13-year-old me thought its name was funny. Its effect on me was profound: I loved how these games played with power and perspective and information and choice, how their narrative turns hit harder and more intimately than in non-interactive fiction. But I was never that interested in the intricate, clever, fiendishly difficult ones. I just wanted to live and move in their worlds, to explore the spaces they had created. (My favourite was Stephen Granade's Child's Play, in which you play a determined toddler at playgroup trying to get your favourite toy back through various toddler-sized schemes).

I think teenage me spotted the same capacity in interactive fiction that has drawn queer and trans people to the form for years: here is a world you can build to your own dimensions, a house nobody can kick you out of. (Books work similarly, but you need a lot more money, time and power to publish a full-length book than to make a text game.) Plus, Twine works through hyperlinks and branching narratives, which works well for people whose stories may be fragmented and blurred. "It didn't demand [...] that I tell a linear story, one that was neat and made sense and contained some kind of resolution," writes developer Merritt Kopas in the anthology Videogames for Humans. "I felt free to just start writing fragments, each in their own passage. The connections could come later." If you get lost, that's often the point.

In these games, there's nothing to prove. If you've entered this world, it's because you want or need to be there, and if you want to stay, you can.

When I started playing trans Twine games, what struck me was how their tough content - violence, abuse, precarity, loss - intersected with a startling kindness towards the player. "Please remember: Nothing you can do is wrong," begins Porpentine's critically acclaimed With Those We Love Alive, which captures a central component of trans Twine games: it's very rare that you can 'fail' or 'lose' or do things wrong.

These games are designed to centre a kind of existence where your baseline reality is regularly denied by other people, where your whole life is like a series of minigames you play to keep yourself safe. (Anna Anthropy embodies this part of transness to great effect in her game Dys4ia.) So, for once, in these games, there's nothing to prove. If you've entered this world, it's because you want or need to be there, and if you want to stay, you can.

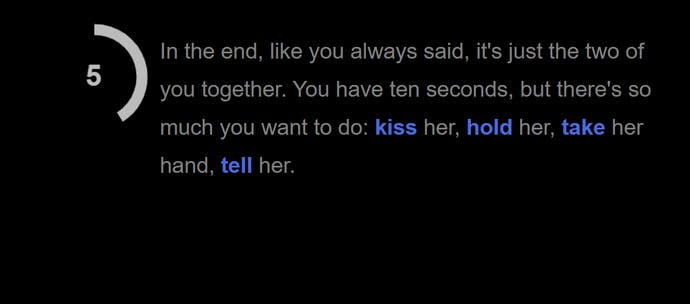

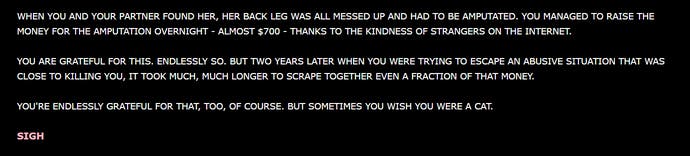

There are aspects of restorative wish-fulfilment in trans Twine games, and also of processing and transfiguring trauma. In Ira Prince's Queer Trans Mentally Ill Power Fantasy, you get up in the morning to find that your body has been replaced 'WITH A GLITTERING IRIDESCENT MECHA SUIT ENCRUSTED WITH EVERY NICE MESSAGE YOU'VE EVER BEEN SENT', which you use to do small, pleasant things that you might otherwise find difficult, like making a good breakfast and petting your cats. Meanwhile, Anna Anthropy's Queers in Love at the End of the World gives you ten seconds to do what you wish with your lover - kiss her, tell her you love her, hold her - before the timer ticks down and 'everything is wiped away.' No gods are toppled in these games: the winnings are survival, a good meal, fleeting moments of intimacy and warmth.

Trans Twine games usually aren't here to instruct and edify a cis player: instead, they land the player on a planet with a trans atmosphere and let them figure out that they can breathe. This Pride month, I've been thinking a lot about how games can facilitate connections that aren't a huge burden on vulnerable people. It's restorative to play games made by people who understand what you're going through, but there's also something lovely about playing games by, say, trans women when you're not a trans woman. You get to share in and find commonality with a different lived experience, you get to stay a while in someone's art, without risking taking up their oxygen. It's a profoundly gentle kind of correspondence.

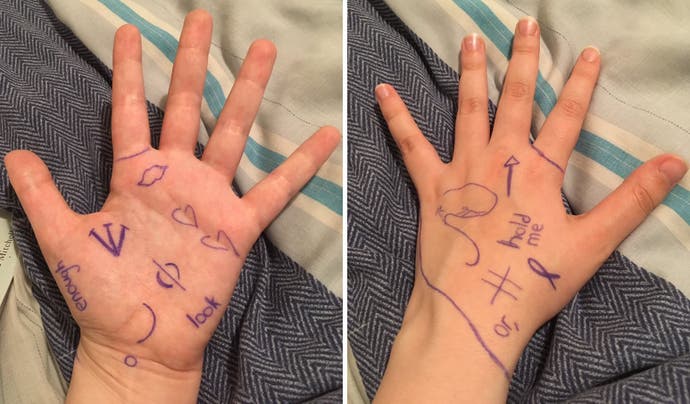

There's a humility and a curiosity required by these kinds of games, a willingness to be moved. As I write this piece, my left hand is covered in drawings. In Porpentine's With Those We Love Alive, the story asks you to draw sigils on your skin at points in the narrative: sigils of shame, of hope, of reaction to the game's events. The trans main character's hormones also take the form of sigils, and when your character looks at them, she thinks precious. Every time.

As in most distressing and transformative experiences, you don't get to choose to be marked, but those charged symbols also signal your human capacity to feel and to be changed. I hope people continue to open themselves up to games like With Those We Love Alive, but most of all, I'm glad for what Twine has given so many marginalised writers and players: a space to breathe, and an opportunity for us to reach across and stain each other.