When the arcade came home: a short oral history of the Neo Geo

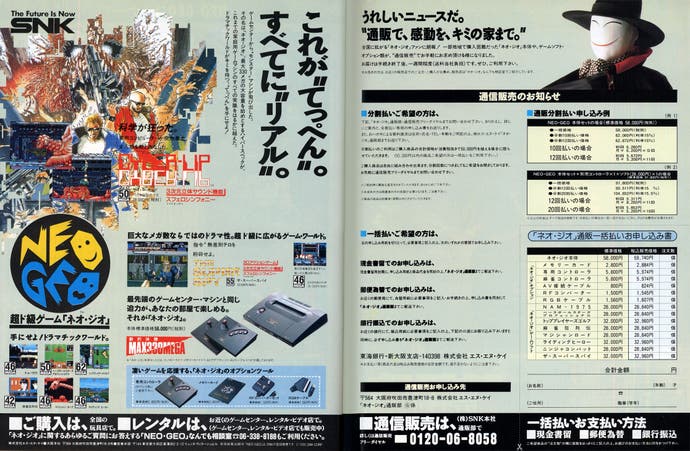

The future is now.

Sega and Nintendo stole the headlines in the 90s, but SNK stole the imaginations of a generation with its exquisite Neo Geo machine, a console that fully delivered on the promise of arcade quality video games in your own home: it was, after all, an arcade machine you could effectively put under your own TV.

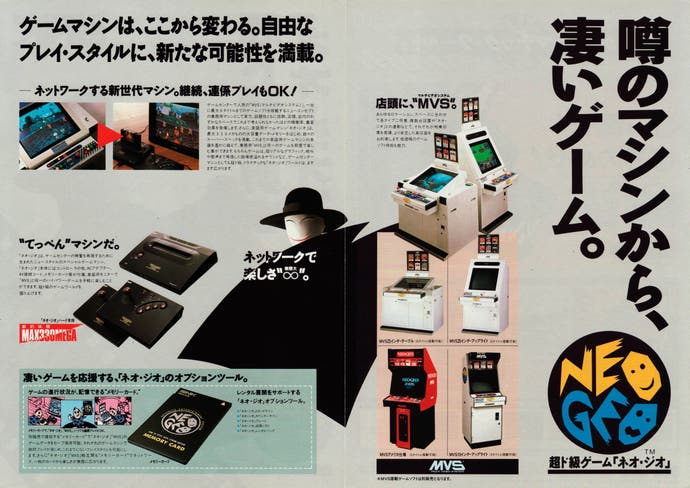

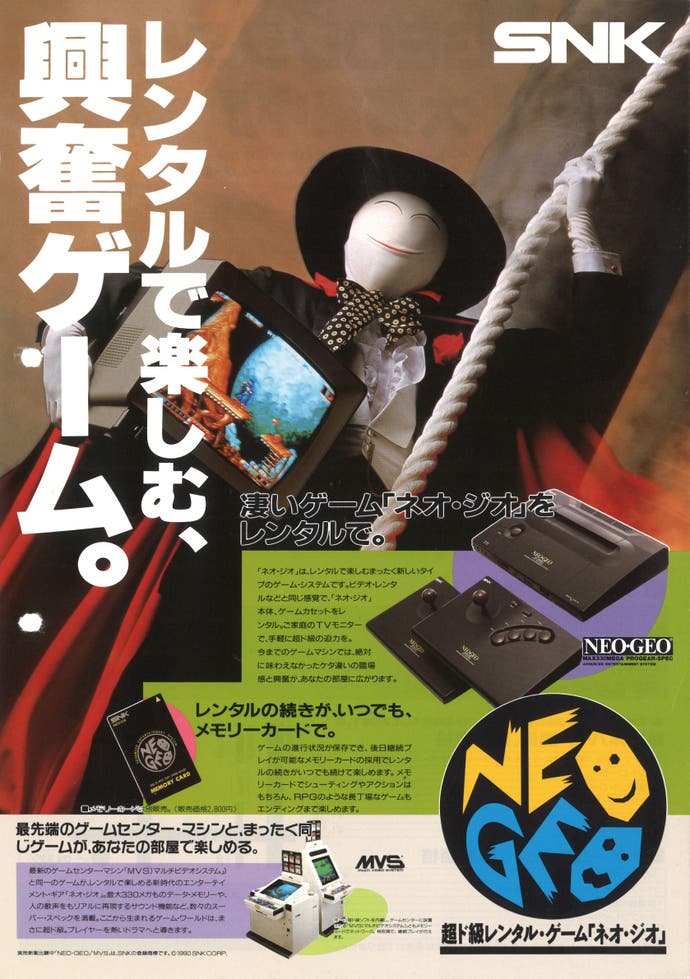

First released in its full-spec MVS arcade cabinet before the home version - dubbed the AES, or Advanced Entertainment System - followed early in 1990, the Neo Geo still stands out as a console with an allure all of its own. Maybe it's how relatively unobtainable they were to contemporary audiences - the console came in at around £500 while games would cost up to £200 a piece - or maybe it's how it arrived just before 3D gaming took hold, its 2D action titles still standing out as a high watermark for the form, but the Neo Geo's appeal hasn't dulled in all the years since.

SNK slipped into the shadows at the turn of the century, the collapse of the fighting genre which was its main trade as well as the commercial failure of the Neo Geo leading to its bankruptcy in 2001. The company changed hands over the years, and changed its strategy in the process, moving from pachinko machines to compilations and new takes on established properties, but it wasn't until 2016 that fully glory was restored, the SNK name being retained alongside that iconic tagline 'The Future is Now'.

Momentum has been gathering ever since, with key members from SNK's past returning to help forge the next chapter in the company's history. After 2019's successful Samurai Shodown reboot, a new King of the Fighters is due later this year, with a new Metal Slug and even word of an all-new console imminent. Before all that, though, we got together some of those who helped make the SNK name so revered to give us an insight into its 90s heyday, and into what made these games so special.

Joining us are vice director of SNK studio Naoto Abe, who previously worked on titles such as Three Bount Count (or Fire Suplex, as it was known in Japan), King of the Monsters and Fatal Fury; Nobuyuki Kuroki, game designer at SNK who previously worked on Garou: Mark of the Wolves before returning to help the most recent Samurai Shodown; and finally Kazuhiro Tanaka, who worked under the name Max D as one of the main artists on Metal Slug 1, 3 and X.

SNK was formed in 1973, going on to make its name in the arcades of the early 80s with the likes of Ikari Warriors, Athena and Alpha Mission (a period wonderfully chronicled in 2018's excellent SNK 40th Anniversary Collection that shines a light on the company's earlier work). It was with the invention of the MVS, though, that SNK entered what many see as its golden era, the modular arcade cabinet that allowed operators to swap cartridges in and out proving remarkably successful.

Naoto Abe: In the 80s, you had the bubble economy in Japan, and all industry was riding really high on that. But in the 90s, it crashed. A lot of people were suddenly out of a job, and the economy tanked. They didn't really have much money. And so a lot of people found themselves instead investing a lot more time into games, going to arcade centres. Even though Japan experienced the end of the bubble economy, the games industry was actually doing really, really well. It didn't experience that kind of implosion, like what happened with the States and the game crash in 1983.

[The games industry in Japan] didn't experience that. And so that led to this rapid expansion, especially in the fighting game scene, and arcades in general. That led to people at SNK - producers, directors - getting more ambitious and making more games because they were experiencing this big rise. There's a lot of motivation to make these big bombastic games as well.

The masterstroke would come when SNK decided to bring the arcade home with the Advanced Entertainment System. When it launched in 1990, the Neo Geo AES was several leagues ahead of the competition in terms of sheer grunt, its cutting edge visuals making some of the most iconic games of the era possible.

Nobuyuki Kuroki: Before the Neo Geo came it was never as if we were going to directly compete [with Sega and Nintendo]. We had this idea that we were going to make these arcade cabinets - but it was about bringing that entertainment home. We were in the same market as other competitors, but we had two ways of getting capital. It wasn't about going directly to beat other competitors, and more about seeing if there's room for us here.

Kazuhiro Tanaka: In terms of specifics, the Neo Geo was meant to be more powerful, stronger and faster than any other competitor out there. And so we already had this really powerful machine in place - now we've got to fill it up with detail and do what we can.

The Neo Geo was a premium piece of kit but it also came with a premium price tag, with AES cartridges costing around four times as much as their competitors, while the console itself carrying a $649 price tag when it released in the US.

Naoto Abe: It was extremely expensive for one game, and the actual system was around 50,000 yen, which was a lot of money at that time. It was a premium experience, obviously. The CEO at that time wanted the arcade quality, but in the comfort of your own home. This wasn't a kid's toy - this was kind of different. It had to be really strong, it was black so it was more premium, it has this real feel to it. There definitely was that adult quality to it at that time.

Nobuyuki Kuroki: Of course everyone's initial reaction was 'jeez that's expensive!' You know, they were really shocked and it was just ridiculous at that time. But for some players, the hardcore gamers - when you factor in how many times they go to the arcade, how many hundres of dollars you're actually putting into keep playing those games, it actually made sense to buy a Neo Geo, you'd actually save money.

At that time there were even super hardcore players that would buy the actual arcade cabinet of a game that they really wanted and actually have that at home now they would pay almost three times the price of the Neo Geo at that time, but you have these extremely devoted hardcore people that went and did that.

To the average consumer, sure it was expensive, but to a hardcore gamer and somebody actually went to the arcade and was all about that lifestyle it was pretty good. And at SNK we had employee discounts, so I was able to get a pretty nice pretty nice percentage taken off of my Neo Geo when I bought it at that time! I bought one when I joined SNK!

Naoto Abe: I was against the idea and didn't buy one! But if you're out there in the arcades - it definitely made sense to our main market.

With headquarters in Osaka - a city whose bawdy spirit puts it in contrast to the more sedate neighbouring Kyoto - SNK was a boisterous, lively place in the 90s, with that energy finding its way into the company's staggering output of games at the time.

Naoto Abe: Back then we were all very young and energetic - we had a lot of power to go! Of course there was a lot of work, and we worked a lot - and we worked until late. But it was fun! We were in our prime, so it didn't really bother us that much.

A lot of the people coming into SNK at that time, especially from different colleges and schools, were very unique. They had really unique, bombastic, interesting personalities. But of course they were also new to the game as well. You did the work you had to do - there wasn't really a slacking off mentality. What was common back then is the work that you've got, you would actually give back a lot more than what was requested of you. You can see that a lot of the games weren't cut and paste type affairs. These games, you get that a lot was put into them.

Nobuyuki Kuroki: Compared to now, whenever you want to make a fighting game or any game in general - indies aside - even when just making one character you need so many modellers and so many animators, you need people to look at the different types of industries in China and America, you need financial planners and all that stuff. But back then, as long as you got an artist, a planner, and a programmer, that was basically all you needed. You could make a game with a really small amount of people, and so as long as the people in that team had that uniqueness to themselves, and really bombastic personalities, you could crank out some really memorable titles.

It's that punky ethos that ensured that these games weren't just memorable - they were iconic. The Neo Geo hosted all-time classics such as King of Fighters '98, Last Blade 2 and the achingly beautiful swansong Garou: Mark of the Wolves. Picking any one title out for particular attention seems a bit unfair, but seeing as we're in the presence of one of the key talents behind Metal Slug, it seemed only right to dig into what made the muscular run and gun series - still a high watermark for 2D visuals, in my own opinion - so special.

Kazuhiro Tanaka: On Metal Slug, I would get something from the planner and then I'd be like 'how about this' and send it back. Of course that would require more work, but that finds itself in the final product of the game. That's why those games are so refined and unique as well.

It was tough. There was a lot of going back and forth. At the very beginning of Metal Slug, it was just going to be tanks - though we realised that was kind of boring. And so they decided to add the first two characters, Marco and Tarma. You could jump into the tank and get out and shoot and all that fun stuff - that made it a little bit more fun.

In terms of the worldview and the world design of Metal Slug, we were instructed to give it this slightly darker tone. When you play the game, it's supposed to not feel super clean, you're supposed to feel dirty and it's this dirty look to it. It's a world that's actually been lived in.

We worked really hard on that aspect and, but also the way that the tanks move. The machines in that world move aren't like the traditional ones. They're made out of metal, of course, but the metal doesn't really move that way and it's more like a living animal in the sense that those movements are more biological, which you can see if you look at the actual Metal Slug itself, it bends in ways that it shouldn't actually bend.

Of course there's that pride in your work that you want to beat other competitors. You have other people in the industry and you want to be better than them! You want to make the best product and show all the other competitors out there that you guys are top dog. So you have that aspect! We looked at our competitors and thought that's really good, and we learned from that, but we also wanted to improve and go beyond what they're able to do.

When it comes to the sprite work and the animations of the characters, you only have a limited amount of pixels. So what do you do with that limited amount? You have to really work hard on making the most of what you had. And that came in the form of making movements - how do you show that movement? The way that we were able to achieve it was by altering the gradiation variation on some of the colours.

One of the tests that we'd give to new animators and pixel artists was to make this extremely small object - like half of a pixel - show some movement, some animation. It was that kind of attention to detail, trying to fill up as much of the space that you can in those games, that really made them really pop out and made them look really good.

Nothing lasts forever, sadly, and with the fighting game boom coming to an end - and numerous other factors - SNK filed for bankruptcy in October 2001. It wasn't a full-stop as such, though the intervening years felt like a limbo period until, with the help of outside investment and a restoration of the old SNK name and slogan 'The Future is Now' in 2016, the company marked its proper return. In the years since we've seen impressive new entries in the King of Fighters series as well as Samurai Shodown, with a new Metal Slug on the horizon as well as murmurings of a new console from the company. They're not plans SNK is able to share more on at present, but as it stands it's steadily retaining its past status, with the old generation returning to help guide the new.

Kazuhiro Tanaka: Of course all three of us are creators, artists, and SNK is a place where we started. At the very heart we're creators, and here we can make what we want to make. And so a lot of people return here with their own conditions - I want to do this, I want to do that. And somebody said 'Well, sure, you know, you guys were here before, why not?' When I returned to SNK, having previously worked on Metal Slug games, I was able to return doing pixel art for the mobile games as well. It's something I really enjoy, and I find a lot of fun in it. It's worked out in everyone's favour at the end.

Nobuyuki Kuroki: The way that games are made greatly differs now. At the old SNK it was small teams, you could kind of make what you want as long as you got it done at the end of the day. There was a lot of freedom. Nowadays there's a lot more planning, and that planning needs to be with a lot stricter measures and you need a lot more people working together, so there's less room for error. But that doesn't mean it's any less fun compared to you know, older SNK. There's still a lot of enjoyment that people get out of working here. It's just the way we make the games that's different.