Beyond Good & Evil

Michel Ancel returns in style.

Hear ye, hear ye! From this day forth, Michel Ancel is no longer "the creator of Rayman". From now on, he is "the genius that brought us Beyond Good & Evil". In his latest game, the veteran designer's skills as storyteller shine like never before, as he introduces us to a cast of memorable and endearing characters, binds them to a gripping narrative and, most importantly, throws them into a compelling and open-ended adventure that satisfyingly blends a potentially incoherent mix of gaming styles without ever frustrating the player. Cast out amongst a slew of Christmas blockbusters, BG&E rises above them all and leaves an indelible impression.

Above and Beyond

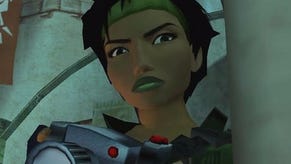

It all starts out innocently and unassumingly as the player takes control of Jade, a young freelance photographer living on Hillys, a planet caught in the grip of a war between the menacing DomZ and the elite troops of the government-backed Alpha Sections, a mysteriously helmeted force tasked with protecting the people from the DomZ' frequent attacks. Raised almost from birth by her half-pig, half-human uncle Pey'j, these days Jade looks after a group of war orphans at her lighthouse home, longing for the war to come to an end so they can all live happily and in safety.

Not long after surviving a direct DomZ attack on the lighthouse, Jade is recruited to help the IRIS network, an underground resistance force trying to prove that the Alpha Sections are using the DomZ invasion as a smokescreen to kidnap Hillyans for purposes unknown. Although initially unconvinced by IRIS' claims, Jade is keen to put an end to the hostilities for the sake of the orphans at home and Hillys in general, and so decides to heed the call, quickly finding herself caught up in a massive conspiracy, working to prove whatever she can in the face of a corrupt media saturated with propaganda and the harsh restrictions placed on the Hillyans under the guise of safety measures. Hrm, sounds familiar...

However Jade is no warrior, and can't simply walk up to the nearest Alpha Section guard, beat him to a pulp and force him to answer questions. Nor can she race all-guns blazing into a suspect area and uncover the truth that way. Instead, with the help of uncle Pey'j and later fellow resistance fighter Double-H, Jade has to infiltrate various key facilities, snap pictures of conspiratorial goings-on and send the photos back to IRIS, who publish an underground paper aimed at raising awareness that all is not as it seems.

Legendary?

Her adventure takes many forms in a game that shares many common elements with the latest Zelda adventure, The Wind Waker - incorporating stealth and puzzle-based elements into dungeon-style environments, simplifying things like combat and platforming so they don't become frustrating and stem the flow of the narrative, adopting a simple heart-based health system (which allows you to juggle health boosting heart slots between Jade, Pey'j and Double-H), and offering all manner of sub-quests and self-contained challenges just off the beaten track, all of which have some relevance to the main, binding narrative but many of which are optional. Furthermore, Jade makes her way around Hillys on a hovercraft (and later another more impressive vehicle), moving between docks in town, at various abandoned and not-so-abandoned facilities, at trading posts and on seemingly innocuous beaches and small islands.

But unlike The Wind Waker, navigating the seas of Hillys is never tedious. The actual playing environment is surprisingly small, but densely populated, thoroughly detailed and well laid out. It also helps that many of the game's hugely varied challenges involve the hovercraft in some way, even integrating it into dungeon design, and that the game's most prized collectible - the pearl, of which there are a large number to uncover - can be used to buy useful and sometimes crucial upgrades for the hovercraft at a memorable local vendor's outpost in the bay area next to the lighthouse.

And unlike Zelda's notorious and repetitive 'fetch quests', BG&E's sub-quests are engaging, from the Looters Cavern sections, in which Jade and companion have to chase down a looter in the hovercraft as he races off with a wodge of dinero, to Vorax Lair, where Jade has to battle through a group of enemies and figure out how to carve a path to a rogue flying creature holding onto a pearl. Indeed, sub-quests are even important right at the start of the game, when you agree with a local science researcher that you'll document animal life on Hillys, and for every roll of film you submit documenting individual species, she not only pays you handsomely but also rewards you first with a digital zoom for your camera, and from then on with a pearl per film.

Shoot-'em-up!

The digital zoom proves especially useful, as Jade's camera plays a big role in Beyond Good & Evil. When you press R1, the game switches to a first person camera view, allowing you to point and zoom with the two analogue sticks, scanning objects for weak points and clues (without an annoying pause ala Metroid Prime), centring on indigenous creatures (which can't just be snapped oafishly, but have to be centred and framed properly) and collecting proof for IRIS - and for the conflicted Hillyan governor, who will happily give you secure access codes if you can convince her it's worthwhile. Although it soon pales in significance compared to her work for IRIS, Jade can continue to collect animal snaps and make extra money throughout the game - and I never thought I'd find myself enjoying the task of sitting on the edge of a bay waiting to try and snap a gigantic whale as it arches out of the water every 15 seconds or thereabouts, so chalk up another point for Ubisoft's cunning designers.

That said, any good photographer will tell you that the basis of a good picture is being in the right place, and Jade certainly has to go through plenty of trials and tribulations to find those ideal vantage points to snap her proof of conspiracy. Along the way, she'll have to stealthily avoid the attentions of Alpha Section guards, whose only weak points are the respirators strapped to their backs, leap, duck and circumnavigate a lot of punishing laser beams, and occasionally work in tandem with Pey'j and Double-H to overcome common obstacles.

To continue the Zelda comparison, BG&E manages some truly magnificent 'dungeons'. Although you won't spend as much time trying to get your head round the layout by pouring over the map (which, ingeniously, you only obtain when you find a copy of it somewhere in the level and manage to snap a picture of it) thanks to a more straightforward, linear style of level design, there are still elements of exploration required to unearth bonus pearls, and it's never less than satisfying to get past a room and onto the next.

Hand-rolled with the finest leaves

Part of this is simply the way Ubisoft has blended so many disparate elements together cohesively, and part of it is that BG&E's puzzle design is so perfectly balanced. In-between and often while you're sleuthing past guards (using L1 to crouch and the camera to make sure you're not poking out from behind a bit of scenery), clobbering indigenous nasties (hackandslash with X, dodge with square), jumping between platforms automagically ala Zelda and jetting around on the hovercraft, you'll have to consider a number of ingenious puzzles, often having to think slightly laterally or scour your inventory to get past a particular obstacle. I don't want to use too many examples, because every puzzle is relatively simple yet extremely gratifying to overcome, but don't be too surprised if you find yourself having to find ways to bash obscured switches from afar when you get hold of a disc-launcher, take advantage of a crane lifting suspiciously graspable crates over a number of impassable lasers, or find a way to divert thrashing cables to power an elevator.

But perhaps the best thing about playing BG&E is that you never feel like you're just ticking off boxes on the way to an end sequence. The game is masterfully constructed, evenly paced, rarely predictable and almost never frustrating - even text input for the occasional lock-breaking code, so often the bane of console gamers, is handled beautifully with a spiralling on-screen keyboard that makes full use of the analogue stick and proves once and for all that sticking a qwerty layout on the screen is lazy and thoughtless.

Then again... Scratch that, the best thing about BG&E is the storytelling. Seamlessly integrated in-game cut sequences, emotive, endearing and well developed characters that... no, who deliver warm, friendly and entertaining dialogue, a sequence of events that genuinely affect and interest you, and the biggest boon of all, a satisfying conclusion. Although there will be those who sit back and gasp with disappointment when it all comes to a close after ten or so hours, with little prospect of replay value, it's disappointment borne out of a desire to share more experiences with the characters. But if you ask me, it ends in the right place, and puts all the key characters safely to bed. Finishing BG&E is like turning the last page on a good book, and for me that's far more of a recommendation than a criticism, and a rare thing for a game, even in these days of heavily scripted and supposedly narrative-driven adventures.

Technique

Complementing the storytelling is a luscious and vividly realised game world that recalls the visual style seen in Rayman but still manages to look stylish and individual. The seas of Hillys are beautifully rendered with a reflective water effect that you don't normally see on the PS2, dungeon design is imaginative and thoughtful - from the sparkling and almost aquatic vision of an ancient mine to the moody brown pipes and endless brickwork of the factory area - and character designs are emotive and precisely animated. Likewise, the voice acting is fluid and fitting - and the soundtrack is everything from moody and sombre to lively and excited, and every flavour in-between (our favourite bit is probably the music from the Akuda bar, where the IRIS network holds secret meetings). BG&E even has an answer to Zelda's twinkling eight-note 'discovery' tune, which hits you like a pat on the back whenever you uncover something useful. Truly, there is love and passion behind this game, right down to the NPCs who serve merely to justify little sub-games, like the air hockey-style task in the Akuda bar, or bit-parts like the Jamaican-sounding rhino-men who sell vehicle upgrades - all of whom are comfortable on the eyes and endearingly childish. The art style is distinctly Rayman-like, and at times that does mean muddy, underdeveloped textures and sharp edges, but it's matured a lot and sustains a consistently high standard throughout.

However the game's graphical sheen is also the bedrock of a number of technical flaws which conspire to shave a point off the final score. Apart from the absence of a 60Hz mode, which I can live with, the game also suffers from regular bouts of slowdown. To be fair it doesn't upset the gameplay all that much, but it's certainly ever-present, and it's also disappointing (although unsurprising these days) to find myself battling with the camera from time to time. Fortunately though the game is extremely straightforward once you get your head round a particular problem, and forgiving in its attitude to restart points, so it isn't so much of a problem in the long run. In fact, although I often felt the camera was being unhelpful, I never yelled at the screen in anger or frustration because I'd just been slaughtered by unwieldy or ill-fitting mechanics. In fact, I never yelled at Beyond Good & Evil at all...

But were I to have burst into the familiar strains of unprintable obscenities, I would almost certainly have thrown in a few choice words for the developer's baffling decision to make the game letterbox only. Playing BG&E reminds me of the time I went out and rented a widescreen VHS of Braveheart, not really knowing what widescreen actually meant. I got over the fact that it had whopping two-and-a-half inch black chunks stuck to the top and bottom of the picture, but it certainly took a while. Quite frankly, doing this to BG&E is a ludicrous and inexplicable decision that mars to some extent the impact and brilliance of an otherwise superb game.

A new pinnacle for interactive storytelling

And it is, apart from a few choice technical hiccups, a marvellous game. It's a game that exhibits real personality and individuality. Ironically it doesn't really do anything particularly ground-breaking, but whereas a lot of games recently have left us revelling in the quality of the mechanics and almost mathematical precision of design, Michel Ancel's latest composition leaves you feeling warm and happy every time you finish playing it, and in this medium there can be no greater triumph than that.

-1-14-screenshot_Laf3S8u.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)