The Da Vinci Code

Nto a cmoletpe dsisaetr.

Alright, hands up if you thought this would be awful. That looks like all of you. Let's continue.

Say what you like about The Da Vinci Code: that it was a hacked out book of religion-baiting hokum with enough bad prose to make even a six-year-old blush, or that it was a riveting thriller with an eye-opening tale of a centuries-old conspiracy of the church. It's tied up in one word: phenomenon. By some divine twist of popularity there'll shortly be enough copies of Dan Brown's novel in circulation to put a giant mosaic beard on the moon.

Suffice to say, with as many books as there are wobbly-legged tables in Eastern Europe, and Tom Hanks flying the flag in the movie adaptation, if you were ever going to make a game of said novel, you'd pretty much put every ounce of effort and investment into the quality of its design, wouldn't you? Well, in some bizarre alternate dimension to this one you would, sure, where capturing the maximum possible sales of a mass-market cultural trend would involve making the game look and play as good as it possibly can.

The truth is, this Da Vinci Code (which is really more the game of the film despite featuring none of the lead characters' voices or likeness), falls somewhere between those two truths. I wasn't expecting roses personally, but the news that Charles Cecil, the likeable chap behind the Broken Sword series, had a hand in the design, was encouraging. Like Michel Ancel doing King Kong, it meant we could at least put some level of faith in it. But forget about pleasing everybody, that's never going to work. With the pages of a book such as this flicked through by all walks of life, if I really wanted to make this game a big-seller, there's just one question I'd be asking in relation to its most relevant audience: would my mum like it?

Well, she wouldn't like the combat, that's for sure. Anything as incongruous as our hero and heroine, hunky symbology professor Robert Langdon and sexy snail-chomping cryptologist Sophie Neveu, beating down a congregation's worth of evil monks, mercenaries and policemen would get short shrift from her. Especially when it involves such a needlessly complex system: you're not just hitting them, you're involved in lengthy battles of attrition where the success or failure of an initial punch results in a grapple which then requires pressing the occurring face buttons in the correct sequence in order to elicit an attack or defence manoeuvre (phew). It's a little bit of mini-game fun at first, but one that takes so long to complete per enemy that you'll grow sick of it before you're even halfway through.

Nor would she enjoy the sneaking - the game's second attempt to bolster the traditional adventure plot with something extra. She'd probably question why you can never tell if you're hidden or in view, why the enemies act so stupidly, or why your character's third-person body blocks out most of your vision. And she'd probably take a little time to mention the huge black borders that occupy the top and bottom of the TV because she notices things like that.

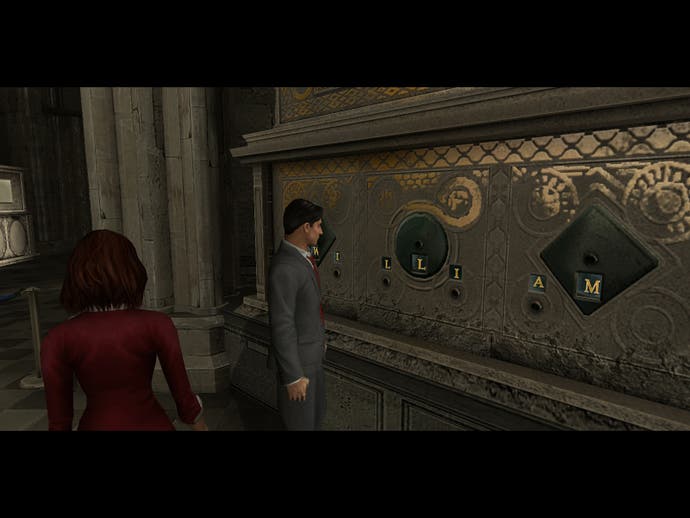

She would like the adventuring, though. Good, strong traditional stuff. The sort of thing you'd expect to derive from its source. Lots of simplistic code-breaking, easy sliding puzzles, polishing grime off paintings to reveal hidden messages, that kind of thing. Even - get this - a puzzle where you have to slide a piece of cardboard under the door in order catch a key dropped from the other side of the keyhole.

Hold on a second, mum, they're having a laugh, aren't they? Surely that old trick got thrown out in the same bag as the text adventure? Apparently not.

Taking those negatives into account, the real problem with The Da Vinci Code is that it doesn't really know who to appeal to. The fighting and sneaking are so inharmoniously overlaid as to render them an irritating chore for those who just want to solve puzzles, yet they're also so poorly done that they're hard to put up with even if you did want them. And the adventuring itself is so traditional that it gains no points for originality, with only the embrace of familiarity to recommend it.

On the other hand, taken on its merits as an adaptation, it does manage to salvage a certain charm. At those points where it remains faithful to the book, I'll admit to a guilty pleasure in vicariously experiencing the potboiler's grand locations and events for myself. When it does spin off into new territory in order to lengthen the experience, it may stretch slightly to the tenuous, but it still stays within the realms of Brown's vanilla-flavoured treasure hunt universe. (Well, apart from that one ridiculous bit in the mansion where you're told that the only way to defeat Silas, the book's evil albino monk, is by shooting him with a ballista down in the basement despite the fact you've just bludgeoned him repeatedly with heavy household objects for the last ten minutes while searching for the ballista's missing pieces. Oh, or the part where he chases you with a firearm down a long, straight corridor missing you repeatedly and illogically with every shot as you endlessly open gates. But, anyway...)

Like I said, when getting on with actual adventuring, it's a rudimentarily enjoyable experience. It puts to use a decent basic interface that allows your standard examining of clues and objects, but it also successfully cribs from Fahrenheit in its use of twiddling and twirling the joypad's sticks and buttons to replicate the minutiae of pulling levers, opening doors, etc. If we can really put all the praise in the overall design glue that just about manages to hold things together at Cecil's feet, I don't know. But the fact is the game's provision of a little more depth than you'd expect shows that at least some care's been applied.

That the expectations were so low in the first place may have contributed to the pleasant surprise that it wasn't quite as stone-cold awful as I'd imagined, yet, it's far from perfect either. The Collective appears to have over-egged the pudding a little, putting far too much needless emphasis on repetitive and increasingly tedious action elements to the detriment of the already unpolished adventuring. In trying to fulfil the needs of what gamers want as well as Da Vinci Code fans, The Collective has ended up with a game that ultimately proves only half satisfying to either and great to none.