Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door

A worthy follow-up to Mario & Luigi.

Order yours now from Simply Games.

Traditionally, Japanese RPGs have been a serious business for all concerned. As a group they're renowned for tackling grand and often sombre themes, and weaving vast, intricate tales through sympathetic characters, believable (or rather, to make an important distinction, not unbelievable) scenarios, sweeping musical accompaniment, considerable exploration, questions of morality and humanity, and advancement through tactical proficiency, amongst a great many other things. And yet Paper Mario and its new sequel reject much of that, arguably proving that you don't have to join the choir to raise the rafters; all it takes is a bit of imagination and a lot of heart.

Or a bulbous retired actress with the ability to blow the paper off the walls.

Ink-redible

Nintendo's latest Mario role-player, designed by the phenomenally bankable Intelligent Systems, has a lot of both imagination and heart. It plays on its characters' origins in two dimensions, and the fact that traditional Mario storylines have been at best one-dimensional, through a mixture of stylistic, flourishing visuals and self-deprecation. It rejects the need for technical opulence, chess-like rules of engagement and a weighty narrative, and manages to concoct something closer to Finding Nemo than Final Fantasy, which is very much a compliment. Here screen wipes reminiscent of paper being scrumpled up, and 2D characters falling comically through gaps in the scenery, are more important than blitzing the player with mere polygons. Here battles are as much about timing and execution as they are about basic statistical superiority, and you would have to be a turtle-guzzling, double-crossing dragon to actually get yourself killed off and stripped from the overall yarn through your actions. And here, most significantly, the overarching drama is not the single most compelling factor.

In other words, the rub - that Princess Peach has been kidnapped while visiting Rogueport, and that Mario has to rescue her and retrieve seven Crystal Stars to open a magical door beneath the town - provides a path to tread, but in truth it's other things - the strength of the characters, their dialogue, the quality of the combat and the level design, and the little dabs of imagination and variety that sparkle in every nook and cranny, as though someone's loaded them onto a magical paintbrush and then flicked it incessantly at the game's papery veneer - that account for our unwillingness to hit the power button again at the end of the night. In fact, it's hard to break down which of its specific elements are the most enticing, because really it's the harmony that wins you over - and the way it never seems to settle into a predictable routine.

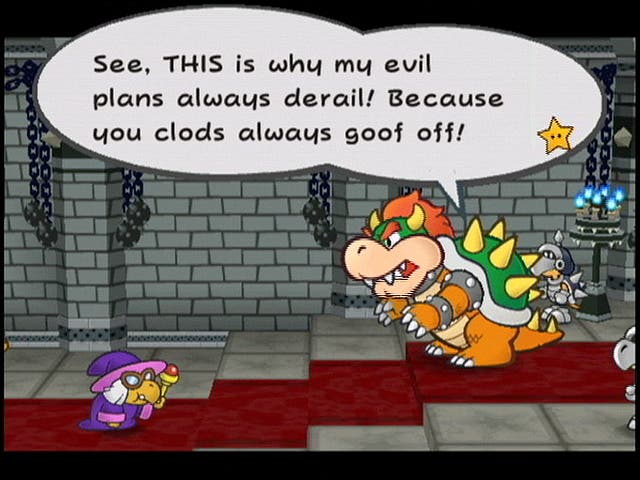

This despite the game's relatively rigid structure. You're meant to collect seven Crystal Stars and then open the Thousand-Year Door of the title, and you do this by taking the treasure map the Princess left for Mario down to the door where it'll show you the location of the next star on your list. After which you have to find a way to get to wherever it suggests, overcome whatever challenges await you, and then return to the door with your newfound star so that it'll light up the next location on your map. The game splits the quest neatly into chapters, and in-between these it rewards you by showing off little in-game cut-scenes that keep you up to date with the bad guys and their progress, and other relevant strands - most notably Bowser and the Princess, both of whom become playable in small enclosed scenarios that are as much about comic relief as they are about story development. Yet for all this it never feels regimented.

Paper sanction

The characters and dialogue are warm and likeable throughout, even when you're in the company of the forces of evil, who, in-keeping with the rest of the series, are as bumbling and incompetent as it takes to amuse, and the script rarely limps through anything, even managing to twist tutorials into wry jokes - like introducing us to the aforementioned bulbous actress and her bellyflop-style attack by promising she'll crush enemies with her "stage presence". As with Super Mario RPG (SNES), Mario & Luigi (GBA), and the original Paper Mario (N64) - all of which, along with PM2, you might consider to be part of the same series - the characters are a mixture of familiar Nintendo faces and new critters based on species from different corners of the game world, and every one of them has his or her own charm and personality, striking up a comfortably humorous tone between them. So much so that you'll actually want to explore towns and villages and talk to people, because you know that nine times out of ten they have something you'll feel better for hearing.

At this point, it would be impossible to get much further without talking about the graphics in some detail. As you can see from the screenshots, the idea is that the whole world is made up of paper - and a lot of the game's best ideas riff on that fact, while more or less every incidental bit of animation or environmental design can be traced back to it. Mario and his fellow residents of PM2 are all 2D, cel-shaded paper cut-outs, who flip round 180 degrees when they turn on their heel, and move and attack in a cartoonish, almost South Park-esque manner. When you enter a building, the side peels down so you can see inside. When you go down a pipe, Mario's papery model twirls round and round like he's being flushed down a toilet. Even your special abilities rely on the papery premise; after an encounter with a weirdo in a box, Mario can transform himself into a paper aeroplane whenever he finds a certain floor tile to stand on, allowing him to find hitherto unreachable items and doors, and a second such ability allows him to turn side on so that he can slip between bars, buildings and other gaps. When you're in battle, it's even possible for bits of the scenery behind you to fall down like stage props. Yet the whole game has a very clean look, despite the relative clutter, and environments have enough depth to them that they don't feel constrained by their limits and the side-on camera.

If anything, it's quite the opposite. Having such transparent limits to the environment means that you rarely feel you're missing anything, and Intelligent Systems has managed to make navigating the environment outside towns far from a chore, too, thanks to puzzles that tumble satisfyingly in the face of a bit of lateral thought, a system of abilities that has you consistently revising the way you look at the game world ("ooh, maybe I can get up to that Shine Sprite now", "maybe now I can peel back that wall in the sewers", etc.), and a battle mechanic that continues to refine the principles that made the other games in the series so popular - even with increasingly jaded role-players. Battling, first, is not random; enemies are plentiful, but you can see them as you explore and generally, with a quick turn of pace or a bit of forward-thinking, you can avoid them entirely, or at the very least make sure you strike first by whacking them with Mario's hammer or bouncing on their head.

Acting up

Once you enter a battle, the game switches you to a stage in front of an audience, where you indulge in some traditional turn-based combat with Mario and one chosen sidekick. Normal attacks include head-bopping, hammer smashes, shell tossing and the like, which can be used each turn at no cost (assuming you don't land on a spiked enemy's head, anyway), while there are also magical attacks (which use up your Flower Points) and special moves - and defensive variants on all. But while it is traditional turn-based combat, that's only in the tradition of the series, which means that normal attacks can involve timing button presses, filling an attack meter, pumping up a gauge, and even aligning a targeting reticule against the clock in order to inflict the maximum damage. Magical and special abilities often go even further; one of your first "special moves" has you tapping A in time with a series of rhythm-action-style progress bars to try and catch you out, while another involves angling Mario's throwing arm so he can knock as many bonuses out of the sky as possible.

Your capacity for Special Moves, though (for they are to be capitalised), can't simply be replenished by visiting an inn or applying some magical remedy bought from the item shop; instead you're reliant on the audience in front of you in the battle screen's auditorium. You're kept up to date with their numbers at all times, and as you pummel an opponent they'll express their gratitude by wafting their appreciation your way in the shape of stars, which gradually fill your special meter at the top of the screen. The better you do, the more people will watch, and the quicker your special meter will grow, and it's even possible - and sometimes advantageous - to sacrifice an attacking turn to appeal directly to them for support. For example, if you're facing a bunch of enemies close to death and your special meter's nearly topped out, you could use your secondary character to appeal and then use Mario to clobber them all in one fell swoop.

Audience involvement doesn't end there, either. Their numbers also include the occasional heckler, who, if left unchecked, will probably toss something damaging in your direction, or even knock over a section of background on top of you. Fortunately if you spot them in time you can press X to tackle them without losing your turn. Of course, given that this is a Mario RPG, even that's not quite the extent of the audience's involvement, but we're not going to spoil the surprise by telling you how else they come into play at various points in the adventure. They're like everything else in the game; they have hidden depths that deserve to be left to you to uncover.

Badge of reason

Like the badge system, for example. You can collect badges (more than 80 of which are dotted around the world) and equip them from the pause menu, and they have some bearing on your abilities, perhaps allowing you to bounce on multiple heads in battle, or enabling you to regenerate a bit of health every few turns. But they don't seem essential to begin with. If anything they feel a little bit superfluous; you can see their benefits, but why not just make these abilities part of the level-up process? As it turns out, because they're a very valid secondary layer of strategy. You won't find all the badges unless you're clever, and when you move between skill levels you'll have to decide whether you want to focus on increasing your capacity for equipping badges at the expense of health or magic, or vice versa. You'll also have to juggle them in your inventory, deciding which to equip and which not. Do you go for a handful of passive badges that help recover health and magic, or increase the likelihood of dodging attacks when critically injured? Or do you pile on the extra offensive abilities in order to make a harsh impression? Badges, then, play a key role, and there's much to discover about them.

What's more, besides mastering attack, badges and the audience, you'll also discover that blocking and countering play a significant role, as they have done in past Mario RPGs. Tap A just before you're struck and you can usually dodge or at least reduce the damage being done to you, while managing to hit B in the split-second before impact will counter and usually knock a point or two off your attacker.

All of which ought to kill them off out right. At the end of a fight, you walk off with a certain amount of experience in the shape of "Star Points", 100 of which will take Mario to the next level of development and allow him to improve his own hit points, or the pooled Flower and Badge points ratings that govern the whole party. Cleverly, Mario is the only character who changes in this way; levelling up other members of your party involves uncovering Shine Sprites and giving them to an old crone called Merlon in Rogueport. Clever because it forces you to keep an eye open. In fact, no; you already had your eyes wide open. Clever because it's a system that allows you to upgrade characters you may not even have been using - in order that they don't get left behind on a lower level like so many other bit-players do in rival role-playing games.

Vinyl Fantasy

Overall Paper Mario 2 benefits from the best of art and craftsmanship. There's very little that you could compare to the levelling treadmill in other RPGs, there's very little forced repetition, and it's the sort of game that smacks of a developer in control of every aspect of what it's doing. Everything's in the right place. And smiling. There are a few minor quibbles, which are sadly inherent to the way the adventure unfolds, but in our eyes they're forgivable - too much back and forth at times can break up the smiles, and there are certain sections where battles mount up rather rapidly and cut through your supplies rather unfairly. The only major stumbling block, potentially, is the volume of text. Most of the story is borne out in speech bubbles, so there's a lot of reading to do, but we've already doused the script in numerous superlatives; and if you don't like reading vast reams of text already then it seems improbable that you've made it this far into a Eurogamer review anyway...

At the very real risk of evoking anti-Nintendo sentiment amongst some of you, Paper Mario 2 isn't just a game for Nintendo fans; it's the sort of game that only Nintendo could make. It's funny without ever verging on crass or incendiary - happy to play on Mario's inability to speak by having him articulate everything through quirky grunts and guffaws, or express disbelief by literally falling flat on his face; assuming he's not busy snoring his way through the cameo-ing Luigi's lengthy description of his parallel adventure to save Princess Eclair in a neighbouring kingdom. And it takes up the sort of jigsaw approach to adventuring that's always served Zelda so well and bends it to its own whim - with each passing hour you'll find something new that radically influences the rest of your quest, so much so that we're simply bursting to talk about some of the things we've been doing, and the familiar faces we've come across. The 'dungeon' design also owes much to Link - take the Giant Tree in the Boggly Woods, for example, which features Pikmin-style minions and precise, Zelda-style puzzles that all eventually unite to reveal the solution. You can almost hear Link's eight-note twang of discovery gently pattering against your eardrum.

It also soaks up far more of Nintendo's recent output than Mario & Luigi, borrowing characters from games like WarioWare, Super Mario Sunshine and others and using them in such a way that you'll either notice, and it'll make you smile, or they'll just be another seamless quirk of the ever-peculiar Mushroom Kingdom. Likewise the audio - much of it is new, and so often brilliant (a special mention here for the Professor's main theme, which is possibly our favourite piece of original Nintendo music since, well, okay, it's got a lot of catchy competition), but there are still cameos for old and familiar tunes that are bound to evoke a reaction - like the jingle you'll hear whenever Mario receives a message through his email device.

And it'll soak up far more of you than Mario & Luigi or the other Mario RPGs ever did, too. It's easy to believe you could spend as long with this as you could a decent-length Final Fantasy title - and there is much to do off the beaten track, whether it's taking on basic side missions at the Trouble Centre, taking part in the lottery (having bought a number, every subsequent day - measured against the Cube's internal clock - you'll be able to check them against a board in Rogueport and win some prizes), creating new items by getting a once-wronged Toad to mix things together for you, playing the slots in Don Pianta's gaff, tackling enemies in a coliseum, or one of a host of other things.

A significant draw

Of course, you've long since realised how this was going to end. But we're trying. We're trying to put ourselves in the minds of people who would treat this game with prejudice and toss it back in our laps and say "No thanks", or just turn up on the comments thread and tell us it's crap, but quite honestly you would have to actually hate Mario, or Nintendo, in order for this not to entertain you. Whether you think you like role-playing games or not. Fair enough, if Mario has stolen your girlfriend, keyed your car, broken the lead in your pencil and signed you up to the Britannia Music Club, we don't expect you to buy this. But the only things we can say against it are specialised nit-pickings. We were honestly going to mention this one occasion when we had to redo something relatively straightforward five times due to our own cackhandedness. That's about as bad as it got for us. Otherwise our only feelings of concern stemmed from our fear that we might not get far enough in quick enough time to be able to tell you with any authority whether Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is every bit as good as Intelligent Systems could make it. Well, we did, so we can. And it is.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)