Pathologic

Broken and beautiful.

There's a term currently bandied around in gaming discussion with wilful abandon. "Living city". It's something of a misnomer. If anything, the term is used to describe the most static of towns, where NPCs amble around with no fixed agenda, perhaps occasional unscripted scuffles of no consequence are used as set decoration. These cities aren't living. The reality is, the city only ever lives when you start changing it.

Pathologic offers a dying city. It's Oblivion with cancer. A pustule encrusted town where events carry on regardless of your presence, slowly wasting away despite you. This is a fascinating game. And a very broken one. And as such, I'm in something of a pickle.

Cards on the table: I really don't know what to do. Everyone sensible hates the stupid blue numbers at the bottom of the page, that the awful people skip to before stamping their feet in ill-informed puff-chested fury. This is why. There's no reasonable mark here. If Kieron hadn't already used EG's Joker Card when giving multiple scores to Boiling Point, it would happen now. But he has, so instead it's compromise, and a desperate plea that you bloody well read the following.

In Two Minds

Pathologic looks terrible. It's a Russian game from 2005, looking like it's from 2000 at the best. But I love how it looks. The FPS controls are awkward, the side-step idiotically slow... like, er, stepping sideways is. Traipsing around the medium-sized city is slow and frequently dull. But there's a reason for that dull journey, and I keep walking. The translation is often extremely poor, descending into unintelligible gibberish. But it contains some of the best writing I've ever seen in a game. Following the plot is often impossible. It's the most interesting and deeply clever plot in years. My poor little head.

Premise: You play one of three characters (the third unlocked on successful completion), each of whom arrives in a strange, anaemic town to meet someone, to find that they have been murdered. And that they can't leave. Or won't. Something's very, very wrong here. I played the fellow known as the Bachelor, Dankovskiy. He's a doctor, researching methods to prevent death. On the promise of meeting a man who claims to be immortal, discovering that he is dead is something of a disappointment. But there's more to it, and people are telling you to talk to people. You begin to explore, walking the peculiarly washed-out streets, and then bump into the Masks.

Two figures, one seemingly a mime with a white mask, the other a large-beaked bird creature, looking as though it's made of wood, but for the breathing. And they talk to you. Not your character. You. And your character gets confused, but they ignore him. This town, they inform you, exists only because of you. You are an actor, the rest are characters. You will know who is important, as they will stand out from the crowd. The rest will blend in.

But you already knew that. Large town with NPCs? Of course the generic clone skins are the unimportant cast, those with specific faces being of consequence. That's Oblivion, that's Deus Ex, it's every damn game. Talk to someone of significance and they have a real-world photograph. Talk to a generic and their representative photograph is a rag doll.

The Masks We Wear

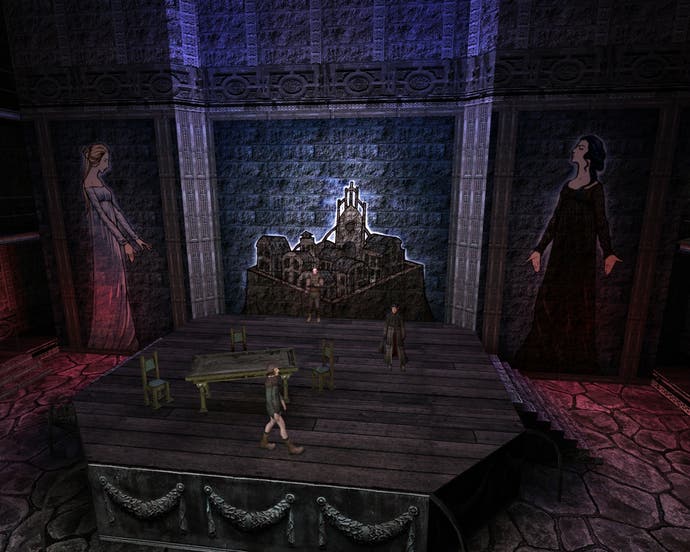

You have twelve days in the town, you are told. There's no pretence that it's not defined. The people don't know, but they only exist because of you, you're told. But you knew that too. You're the player. And this is no one-off smug reference at the start. Every night, after midnight, your quest log clears, and the Masks at the local theatre puts on a play based on your day, and your internal turmoil.

Each day lasts a few hours of real time, with key events occurring when they occur, whether you're there or not. If you're not, someone important might not survive. The ten most important are the Adherents, and you're told early on by a Mistress - a psychic - that these ten must survive, because there are the ten that would die for you. These are the characters of the main story. There are seventeen more with whom you interact on a more voluntary basis. Side quests. But all integral to the plot. Which is, to give as little away as possible, the real reason why people are dying. Something so serious that even the buildings are dying from it.

Quick anecdote: It's Day 2 and my landlady suggests that perhaps escaping the town might be a better idea than trying to save it. I figure, if I could help her get out, that would be for the best. She gives me a contact the other side of town. On the way I stop in at the shelter, having received a note from the lady who runs it. The town is cut off, and food is scarce, prices exorbitant. She asks me to visit a few people who have offered to donate money to her shelter, and use it to buy supplies. So, on the way to the contact's house, I drop in to collect from others and pop into shops en route. The contact needs me to persuade his twin brother, and that requires proof of the severity of the situation. More work, more shops, drop the food off at the planned shelter building. Which is pulsing green inside, smoke coming from the walls, dead bodies, crying, and stood in the middle is the bird-Mask, named the Executor. Bad. More work. She and I change the shelter plans, and I've got the proof to enlist the brothers. We arrange to meet at the train station at 10pm.

I busy myself until then, visit some areas I'd not yet checked out. It's 9.30pm so I head over to the overgrown train yard. No one's at the entrance, so I walk around the back of the vast building, to where a couple of carriages sit on a track leading out of town. And from out of the mist, three patrolmen and... the Executor. Silently shaking his beaky head at me. My heart sank. "Oh shit," came out my mouth. And I told them I'd not try to leave again.

That's Pathologic.

Estranged Alienation

It's really broken. It's far too broken to justify the £25 price, and certainly too broken for me to recommend you buy it. But oh my goodness, I'd love for you to experience this. This is a really intelligent game, suffering from a terrible engine and a struggling translation. But both earn respect. Give a great artist some thick wax crayons and scrap paper and she'll still make something impressive. Despite being very primitive, the town visually portrays all that is necessary to communicate with you. The textures may be incredibly low quality, but a building can still look wretched, covered in blisters and sores. The ludicrous short draw-distance becomes incredibly effective fog. The ridiculous weather effects... well, they're fairly ridiculous.

A very few lines are spoken aloud by European and American actors, perfectly translated. But the majority are written, and swim in and out of consciousness. It's not excusable to release games poorly localised, and Pathologic falls short of the 7/10 I so desperately want to give it because of this. But when it works, it works so beautifully. And when it doesn't, it's occasionally, accidentally, amazingly poetic. It's just so full of ideas, and ideas on which it delivers.

The understanding of the theatrical works of Bertolt Brecht is so very clear. This is a game that wants to create critical self-reflection in its player. It's always a game, and you're not allowed to forget that. It wasn't a mysterious bird-figure blocking my exit at the train station. It was the Game, telling me no, this was an edge, a literal and metaphorical invisible wall past which I could not cross. This is a game of metaphor made literal, that hopes you'll listen and explore the metaphor in your own world. It's Brecht's Verfremdungseffekt. (Yes, twice in a week. Random events segregate non-randomly). And it does this not to try and look clever, but because it is clever. Explore the South West of the town and you'll find the Polyhedron - an impossibly contorted geometric building where the town's children live. (The children are another 1000 words' worth of intrigue). Look closely and you'll see this building is literally made out of its own blueprint designs. The walls are graph paper, the designs sketched across its stretching staircases and tilted walls. It's the construction of its own design - it represents the game itself.

Open Ending

There's so much more to talk about. The midnight theatre, the constant sense of doom, the apocalyptic presence, that when you kill someone innocent an invisible child sobs, the music... Ok, I further ramble over my word limit, despite wrapping the review up 500 words ago, because of the music. It's just amazing. Broken, as is everything here, but changing with the mood, and indeed changing the mood. Swirling background ambience develops tribal drumbeats, evolving a crescendo of threatening intensity, before diminishing into gentle strums.

It's a 6 out of 10 game. I've come to a sort of peace with that in writing this. But it's probably the most interesting and brilliant 6 out of 10 game you'll find. £25 is far too much for a poorly translated, dated game. But at the same time, there's a reason this won every Russian Game of the Year award in 2005. It's the result of extremely clever writers not being married with extremely talented game developers. To think what this would have been in the hands of a funded team is too depressing. As it stands, it's a wonderful obscurity to explore, a thousand caveats accepted and understood, but when it appears on the bargain shelves.