Prisoner of War

Review - Codemasters reinvents stealth gaming

Ve have vays of making you buy zis game

It's clear from the off that most of the characters and events in Codemasters' Prisoner of War have drawn inspiration from the various icons of war film drama. It's a game full of angry German guards, unpleasant camp commandants and wily prisoners, who range from the eager and comical to the cold and cynical, and their loyalties waver almost as much as your trembling fingers when you're poised to race between two inattentive guards.

The game's star is Captain Lewis Stone, who finds himself shot down and separated from his co-pilot during an important surveillance mission over the German lines, before being remanded into the custody of a holding camp, awaiting transfer to Stalag Luft 1. With the premise never in any doubt, I was able to wrap myself up in the events of the story, but even at this early stage the game's lack of polish caught my eye. The opening cinematic sets the tone for dialogue throughout the game - candid lines spoken well but without the flow of a conversation. For a game that will be remembered for the strength of its period portrayal, irritating gaps in speech set the wrong tone.

Once inside the holding camp though, with some dialogue behind you and a handful of prisoners to mingle with, it's a different story entirely. Your mind immediately leaps to the prospect of escape, and you are given the chance to explore the mechanics of the game and the lovingly recreated POW camps, carefully designed and realised by the game's developer. Some of them - Colditz being the best example - are immense, and the flow of prisoners back and forth in large numbers really does recreate the feeling of films like The Great Escape. Naturally you aren't the only POW with a desire to escape, and in the larger levels you often have to impress the escape committee to have them sanction and fund your actions.

Role Call

Captain Stone's adventure is viewed from the third person, with L1 switching to a first person perspective and the left analogue stick controlling movement. The various face buttons serve a number of different functions. You can duck down, pick up and drop items, clamber over wire mesh fences, and you can also save your game when you're standing next to your bunk, or deposit and retrieve items from your safe box. Smaller objects, such as camp currency (virtually anything that shines), rocks and keys are collected by walking over them - you collect a variety of objects on your travels, and stashing them away is often the only way to keep hold of them until they are needed.

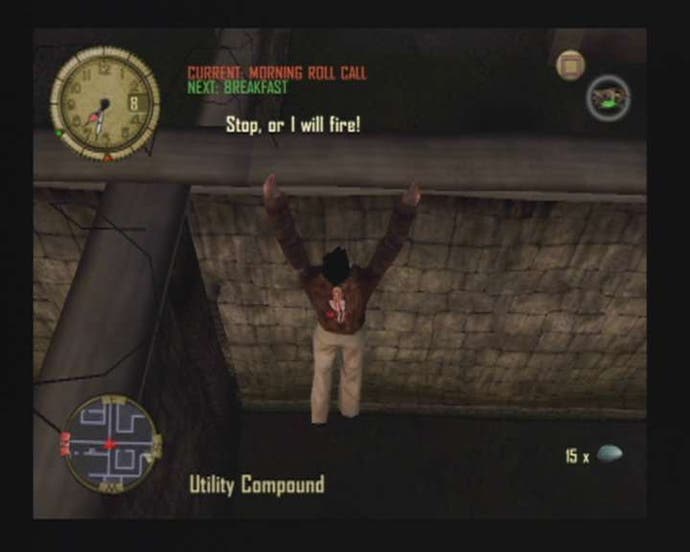

Stone's day-to-day routine is detailed in his notebook, which he keeps in his bunk. If he were to act like a model prisoner, he would attend meals, exercise sessions and so-called 'free time' as well as roll call, which is obligatory, pretty much on pain of death. A clock in the top right of the screen shows the passing of minutes and hours, and making sure you show up for your next appointment can ease the guards' suspicion and allow you to sneak around with greater ease when their backs are turned.

Stone's handy radar shows the guards from above with cones representing their fields of vision, and evasion is his primary concern. Although sneaking around will set them off, simply obstructing their duties or walking too close to the fence can have an unhelpful effect, and don't think that just because you can climb a flagpole they will put up with it… [Don't laugh, this is actually the first thing I did on arriving at the holding camp, thanks to an unfortunate misinterpretation of an on-screen icon. The guard's weren't amused - Ed]

The Plan

Stone's fixation is on escaping, and from the very outset it's a complicated undertaking. After making the acquaintance of his fellow prisoners, he has to steal a small amount of currency from the camp's equivalent of a hospital, before half-inching a key from the guards' quarters and sneaking into a tool shed to remove a crowbar. The tool shed is on the other side of the camp, and provides Stone's best lesson yet in escape etiquette.

Creeping along behind his sleeping quarters, preferably after dark, Stone has to pay attention to guard patterns and jump the fence at the right instant. Thereafter, he has to duck through a hole in the masonry on the other side of the road, the location of which he paid good currency for. On the other side he crouches next to some sandbags and observes the patterns of two guards on the ground and two in opposing watchtowers, and at precisely the right moment he makes a break for some logs stacked near the foot of a watchtower. From then on, it's a simple matter of negotiating the open ground between the stacked wood and the tool shed, unlocking the door and slipping inside. Oh, and then working his way back to his bunk before sun-up and roll call.

Should Stone come unstuck, perhaps slipping into a guard's field of vision, that guard's cone will gradually change colour reflecting his alarm, and Stone's actions will be met with a terse outburst of his vernacular. If Stone can't conceal himself before the guard comes running - perhaps in one of the many bushes strewn around the camp, or amongst some crates - then he runs the risk of ending up in solitary confinement, or worse, being shot. At this point, you either reload your last save or keep going, but being caught or shot shows up as a black mark on your camp report - the end of level screen - so completists will want to retrace their steps.

Corporal Punishment

One issue here is that getting caught after collecting the crowbar is still enough to retain it. One of your fellow prisoners with a thick Irish accent can bribe the odd guard into returning confiscated contraband in exchange for some currency, and for some reason the crowbar falls under this banner. As it happens, the overzealous guards will often search you and uncover your various pocket items as a matter of course, so the retrieval does serve a function, but with plentiful currency it also removes some of the challenge, and it's a fixture of levels beyond the holding camp as well.

Stone's actions grow bolder and more interesting as the game wears on, and camps grow in size, population and guard quotient. His objectives vary from picking locks and stealing more equipment to sabotaging vehicles or hiding away in them, all the while trying to evade the clumsy guards by crouching beneath raised huts, nipping behind objects and throwing rocks to distract them. And as objectives become more elaborate, the tension becomes more and more tangible and the experience is extremely engrossing. Although you can save any time you like, midway through a complicated mission you can't just hotfoot it back to your bunk and do so - gaining ground by negotiating guard routines is an intangible reward and leaves you without the option of easily turning back.

Sadly, while Prisoner of War succeeds in freeing itself from the shackles of stealth templates like Metal Gear Solid, it doesn't share their greater production values and feels very glitchy. The graphics are PS2 standard, with lots of detail but a fair amount of angles and jaggies, and a lot of transition animations are also missing, which spoils the illusion at times. Coupled with the dialogue imperfections mentioned earlier and the perhaps unresponsive and occasionally unintuitive control system, frustration often stems from the game and not your actions. If it's a pill you think you can swallow, however, then POW will quickly become one of your favourite games. Unrestrained by the traditional boundaries of the stealth genre, it executes a neat concept with some grace, and manages to make a decent-sized game out of it. A couple of months of extra polish wouldn't have gone amiss, but once you get used to it, the patient, rewarding experience of the game shines through, and you'll feel a bit like Steve McQueen. And that's almost worth the asking price alone.