The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess

Deserves a spotlight.

Rob's take

Ask someone to define videogames - to explain what makes games tick, what the genetic code is that makes them distinct from any other pastime or medium - and at some point in the explanation, most people will probably mention Zelda. Quite rightly so; along with a handful of other games, the Zelda series boasts a history of design decisions and inspired moments which redefined how we play with broad, sweeping brushstrokes. From its simple yet perfectly balanced mechanism for upgrading your abilities as you play, opening up new possibilities in old areas as it does so, to its stoic and silent - yet eminently sympathetic - hero, Link, countless aspects of Zelda's design have influenced the very basis of hundreds if not thousands of other games.

Like its stablemate Mario, Zelda evolves in a slow and measured fashion. Key aspects of the franchise which simply work well are retained from game to game,and new gameplay mechanics or elements are often treated as experimental. However, also like Mario, Zelda underwent a revolution with the introduction of 3D; along with the groundbreaking Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time set a bar for adventure and action in a free-roaming 3D world which remarkably few rival games have managed to vault, even now.

Once again mimicking Mario's strategy, Zelda took a controversial side-trip on the GameCube - although while Super Mario Sunshine is widely considered to have simply been a weak title, The Wind Waker provokes more debate. A divisive graphical style and some slightly disappointing padding later in the game are enough to render it deeply unpopular in some quarters; others, myself included, consider it to be different but nonetheless brilliant, standing proudly alongside Ocarina of Time (and its darker sibling, Majora's Mask), albeit wearing funnier clothes.

And so, to the Wii. For the first time ever, Nintendo is launching a Zelda game alongside the release of a new console - its most risky and innovative console ever, at that. So then, the most risky and innovative Zelda ever, too?

Key of the Twilight

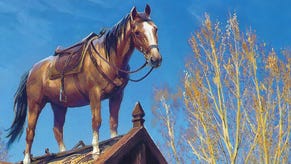

At first glance... No. In fact, Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess seems a little disappointing on that front, at least initially. The game was designed for the GameCube - and will be launched on that platform a week after the Wii version emerges - and it shows, not only graphically, but also in terms of the gameplay. The Wiimote is used, essentially, as a targeting pointer - you fire arrows, pellets from your slingshot and so on with it, or use it to spin the view around in free look mode. In combat, you swing your sword by slashing with the Wiimote, and perform a spin attack by shaking the nunchuck - it feels good, but it's quickly apparent that you're not actually controlling the sword; instead, the slashing movement is interpreted as a button press, and Link swings his sword just how he would if you'd pressed a button, regardless of how you held or moved the Wiimote.

In effect, then, the Wiimote isn't used for anything that you couldn't do with a control pad - but it's arguable that that doesn't actually detract from the game in the long run. The simple fact is that pointing at the thing you want to grapple is more fun than moving around a cursor with an analogue stick, and thrusting forward the nunchuck to bash an enemy with your shield is more fun than pressing a button. The final effect is the same, of course, and some have argued that it makes combat more imprecise, but in a game where precision combat is hardly the order of the day in the first place, that's not going to be a concern for the majority of players - who will instead find that replacing button presses with gestures is at best, something of a plus point, and at worst, merely no better than the old system.

However, for those seeking a new game which fully exploits the potential of the motion sensing controller and puts the player into Link's leather boots in a more immersive way than ever before; sorry. This isn't the Zelda you're looking for.

And once you get a few hours into it, I challenge you to give a damn about any of that.

Everything Changes, But Nothing is Lost

Just because Twilight Princess doesn't innovate in terms of control doesn't mean that it doesn't innovate, you see - and more importantly, and more obviously, it doesn't mean that the game doesn't evolve. It does both of those things, taking the firm foundations established by Ocarina of Time and - crucially - the darker, sadder world of Majora's Mask, and building upon them a game which is beautiful and finely balanced, both intriguing and rewarding in equal measure.

Link, this time, is a young man on the cusp of adulthood - a humble goat-herder in a remote but friendly village, where unlike the troubled or isolated Link of previous games, he is widely liked and cared for. Many key story elements return from earlier games - but nothing remains quite the same. The kingdom of Hyrule is still here, but it has grown and matured, and bears the scars of that maturity as well as being enriched by it; Princess Zelda, too, is older, a sad figure who is nonetheless a brave and passionate leader of her besieged people.

As the game begins, Link's relatively humble adventures around his home town - somewhat menial but wonderfully designed introductions to your various abilities, and to the game's fantastically balanced chains of cause and effect - gradually bring him into contact with a lurking darkness beneath the surface of the world. This darkness forces its way into his life when some of the children of the village are kidnapped, and the nearby woods descend into an artificial and haunting twilight - an eternal twilight which has settled over the entire kingdom of Hyrule, and which Link must save it from.

Along the way, players familiar with Zelda will find that many things have changed under the skin of the game. Link, while still a silent figure, is a more endearing character than ever before, driven initially by his desire to find his kidnapped friends and far more expressive and affected by some of the terrible things he encounters along the way. The animation of his facial expressions is relatively simple but used in a perfect and understated manner - through a combination of this, and the reaction of other characters to him, he develops a sympathetic and complex character without ever uttering a word, while simultaneously allowing enough of a blank slate for players to project themselves into the game.

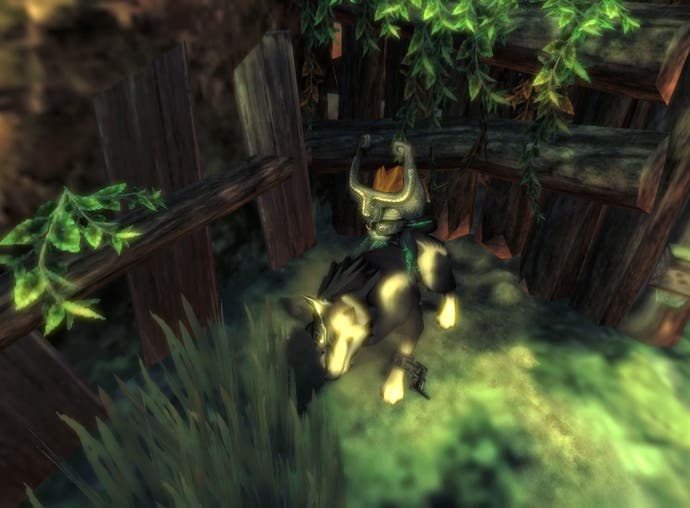

This updated, adult Link, no longer the lonely outsider he was in previous games, is offset by his second physical form - that of a dark-furred, blue-eyed wolf, which he takes on when he enters the twilight world. In this form, even his friends don't recognise him - and moving through the spooky, discordant twilight, humans appear only as small floating lights, whose thoughts Link can discover using his heightened animal sense, but who cannot perceive his presence. Strange, sad moments when he stands next to his closest friends but cannot be seen by them, or is recognised only as a beast, abound in the game, and the overriding theme is one of loss and rejection, as Link's adventures and heroic feats perversely seem to make him more distant from those he cares for, not closer.

All of which is beautiful, stirring narrative stuff, and represents a truly wonderful leap forward for Zelda and its protagonist. While sticking firmly with the it-ain't-broken game structure of having Link move through a world divided into overworld areas and challenging, intricate temples with bosses at the end, Twilight Princess manages to deepen the experience and the emotional connection at each point, building a richer and more compelling chronicle to tie together the locations and puzzles and keep driving the player forward.