Reality Crumbles: Whatever happened to VR?

From the archive: a look back at virtual reality from before the emergence of Oculus and Morpheus.

Most Sundays on Eurogamer, we dig an interesting article out of our extensive archive that we think you might enjoy reading again or may have missed at the time. In Reality Crumbles, written in April 2012 well before the emergence of either Oculus Rift or Project Morpheus, Damien McFerran looked back at the seemingly failed phenomenon of virtual reality. Little did we know how strongly it would come roaring back.

Located on a rather nondescript industrial estate in a suburb of Leicester you'll find an equally nondescript warehouse unit. Nestled amongst the usual glut of logistics companies and scrap metal merchants, the building in question once housed a firm that was poised to dramatically alter the world of interactive entertainment as we know it, and worked with such illustrious partners as Sega, Atari, Ford and IBM.

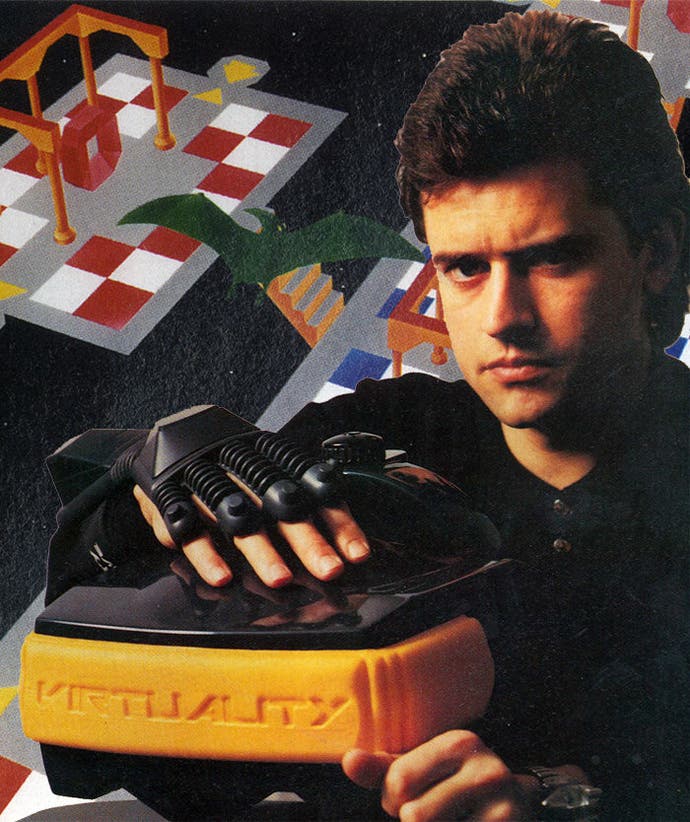

That company was Virtuality. Founded by a dashing and charismatic PhD graduate by the name of Jonathan D. Waldern, it placed the UK at the vanguard of a virtual reality revolution that captured the imagination of millions before collapsing spectacularly amid unfulfilled promises and public apathy.

The genesis of VR begins a few years prior to Virtuality's birth in its grey and uninspiring industrial surroundings. The technology was born outside of the entertainment industry, with NASA and the US Air Force cooking up what would prove to be the first VR systems, intended primarily for training and research. The late '80s and very early '90s saw much academic interest in the potential of VR, but typically it took a slice of Hollywood hokum to really jettison the concept into the global consciousness and create a new buzzword for the masses.

"The fundamental driver was public interest," says Kevin Williams, who worked at another UK-based VR company during this period, and has since become something of an expert on the topic. "The 1992 motion picture The Lawnmower Man boasted ground-breaking CG special effects that encapsulated what had been written and reported about VR, and drove imagination in a similar way to how Steven Spielberg's Minority Report recently fuelled perception of what augmented reality can offer."

It wasn't long before savvy developers saw potential applications in the sphere of interactive entertainment, and given the groundswell of interest in the tech, it was fairly easy for an energetic start-up like Virtuality to capitalise. "The company was the UK superstar of the VR concept," adds Williams. "They were willing to self-promote to publicise their vision of how VR worked, and took a route to adoption through the amusement sector - an industry that was at the time trapped in a downward spiral, in need of unique technology to distance itself from the erosion started by the home console revolution." VR was about to become huge news, and Virtuality had jumped on the bandwagon at precisely the right moment.

Anything is possible

"I started my career at Rare, writing games on the early Nintendo and Sega consoles," recounts former Virtuality staffer Matt Wilkinson. "I'd been making 2D games for about a decade at that point, and then Doom came out on the PC. All of a sudden you were wandering around in what felt, to all intents and purposes, like a real 3D environment. Shortly after that, I heard of a company called Virtuality, which wasn't too far away from Rare's Warwickshire HQ.

"One Saturday I knocked on the door and gave some guy my CV. Completely out of the blue, he showed me round the place, and I was immediately fascinated. There were large pods to stand and sit in, hardware boards lying around all over the place, cables and bits of PCs in various states of disarray. Despite the fact I was in a windowless building on a Leicester industrial estate, the whole place felt high-tech, and seemed to be a glimpse of where the future might lie. The guy let me have a go on Dactyl Nightmare, one of the company's early games. The game itself was terrible, but the experience of putting on a headset and being immersed in a world was incredible. I knew I wanted to be a part of this. The guy who opened the door turned out to be Jon Waldern. He offered me a job, and I accepted."

Virtuality's Midlands setup also impressed Scotsman Don McIntyre, who was fresh out of university clutching a MSc in Computer Science. "It was the scale of ambition that really struck me," he remembers. "From end to end, the operation was slick. The machines looked good and on the whole functioned very well, and the software was literally years ahead of its time." To budding development stars like Wilkinson and McIntyre, VR represented the next big thing in video gaming.

"Kids like us - who had grown up coding on machines like the ZX Spectrum, VIC-20 and BBC Micro - found their way into the games industry and brought with them a lot of ambition and energy," enthuses McIntyre. "The concept of 'immersion' within a fully 3D environment had been around since Philip K Dick and extended a little further with Disney's Tron, and we grew up reading those books and watching those films. It felt like anything was possible."

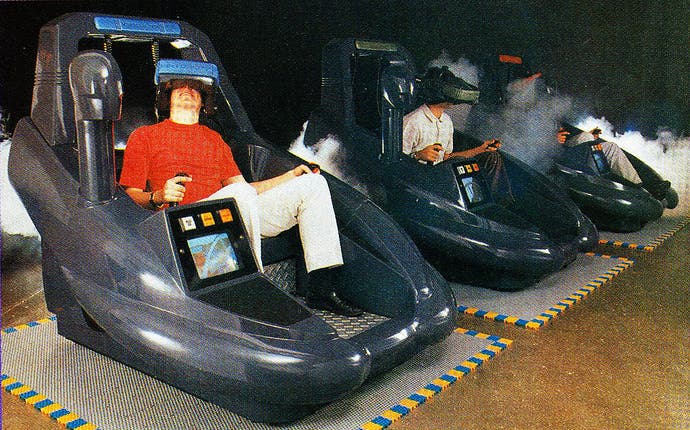

Virtuality's hardware was initially quite crude, with games like Legend Quest and the aforementioned Dactyl Nightmare sporting painfully simplistic polygon visuals and terrible frame-rates, but the underlying tech improved as time went on. "There were two generations of both stand-up and sit-down machines," elaborates McIntyre.

"The 1000 series, which featured the iconic bulky headset, and the 2000 series, which was far more advanced in terms of hardware and software capability. The 1000 series was essentially an Amiga 3000 with our own proprietary cards based on a Texas Instruments chipset. The 2000s were tricked-out 486 DX4 PCs." Virtuality's unique pods offered gamers their first real-world experience of VR, but due to the myriad problems the concept faced, it didn't always leave a positive impression.

"At the time, a top-of-the-range coin-op game would cost you 50p to play, or perhaps a quid for Sega's fancy G-LOC R360 cabinet," reveals Wilkinson. "But those games were ones that everybody knew how to play. VR machines, in contrast, were totally alien. Therefore, you needed an attendant to help you into it, persuade you to put on the sweaty headset, and talk to you via a microphone to stop you standing in a virtual corner, staring at a virtual wall for your entire three-minute experience.

"To cover the prohibitive cost of the hardware and the added expense of having an attendant on every single machine, the player would be charged on average four pounds to play for three minutes of not really knowing what they were doing. The VR experience is not something that can be quickly learned or mastered, so three minutes was never going to work. But these were amusement arcades, and the average arcade owner wants as many people in and out of the machines as they can in a day."

With VR struggling to find acceptance in the coin-op sector, inevitable attempts were made to introduce the concept into the lucrative domestic arena. Nintendo's VR-inspired Virtual Boy was a commercial disaster, while Atari created a VR headset for its ill-fated Atari Jaguar console, with Virtuality providing the expertise.

"We designed a very low-cost unit with head tracking," remembers Wilkinson. "The method we pioneered is actually what the Nintendo Wii uses to track the pointer, but in reverse; on our headset, the IR receivers were on your head and the transmitter sat on your desk in front of you. Bearing in mind the relatively low cost, it worked remarkably well, but of course it suffered from all the obvious problems - occlusion of the IR broke the tracking, turning your head too much would typically put one of the receivers out of sight of the transmitter and moving your head around could easily put you out of the ideal range, which impacted the smoothness of the tracking."

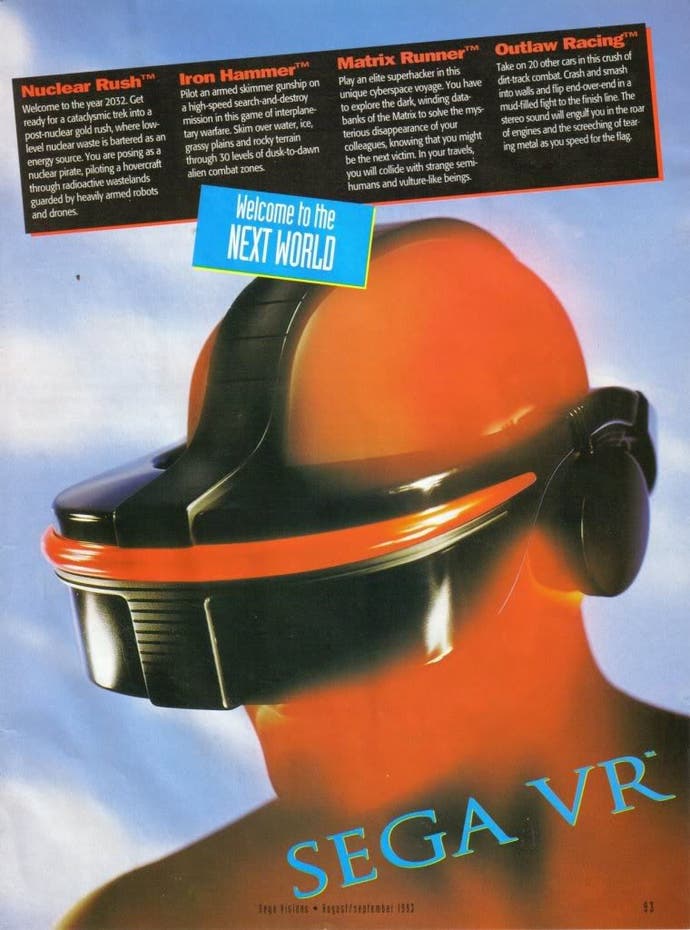

In addition to the Jaguar headset deal - which ultimately ended in tears as Atari began to backpedal in the face of crippling losses and increased competition from its next-gen rivals - Virtuality also assisted Japanese veteran Sega with its own pet project. Along with Atari, Sega was seemingly gripped with temporary VR fever in the mid '90s, and was tantalisingly close to releasing a headset for its ageing Mega Drive console.

"The company wasted a lot of time playing with a coin-op prototype that used technology licensed from Virtuality, while at the same time it also developed its own headset using licensed components," explains Williams. "The arcade prototype would fall by the wayside, though the hardware would be developed into the first VR theme park attraction - dubbed VR-1 - which was deployed in a number of Sega's Joypolis venues in Japan."

Thinking outside of the box

These projects were little more than flights of fancy for the established gaming giants; throwaway projects based more on curious speculation than serious business. But back in the UK, Virtuality's ailing coin-op business - its bread and butter - was in serious trouble. The company simply couldn't deliver on the sky-high desires of the public, which were fuelled by laughably unrealistic depictions of VR in movies - ironic when you consider that Hollywood played a massive part in creating awareness and initial demand for the tech in the first place.

"When the movie Disclosure came out in 1994, it boasted a VR segment which really put a huge dent in what Virtuality was doing," recalls Wilkinson. "Up until that point, we'd been happily telling the people that were paying us huge sums of money for their VR experiences that this was as good as they were going to get with the technology available at the time. Disclosure then puts a fresh Hollywood spin on VR, and suddenly all you need is a pair of lightweight glasses and you're wandering around a photo-realistic version of the world; this was what people now wanted, not a simplified, polygonal environment."

To shore up its crumbling business, Virtuality had no choice but to diversify and take on commercial projects unrelated to the entertainment sector. "Jon asked me to join what was known as the Advanced Applications Group," Wilkinson explains. "We did everything from putting the user on an oil rig that was blowing up to creating a VR experience that - intentionally, I might add - simulated a migraine. It was at that moment that I finally saw VR for something beyond just gaming; I realised that it had huge potential in all manner of other areas.

"Another AAG group worked on a project that was a simulation for anaesthesiologists; the user would be by the operating table of a patient, with an accurate representation of the controls and array of things available to a real anaesthesiologist, and their job was to make sure the patient was calm, stable and basically didn't die. The instructor could suddenly cause all sorts of things to go wrong that the user would have to deal with and keep the patient alive. This wasn't a game; this was going to save somebody's life one day. Similarly, the oil rig simulation was designed to test layouts and signage within a rig to see whether people would be able to follow the emergency instructions and get to the lifeboats in a very intense situation. Once again, that may have saved somebody's life, and that was serious potential."

Born from a desire to expand the horizons of science but appropriated by the games industry for entertainment purposes, VR had ironically now come full circle. Another delicious irony is that Virtuality finally found its gaming mojo around this period - although sadly, it was too late to reverse its fortunes, or the damaged perception of VR in the public eye. The game in question was Buggy Ball.

"Four players played simultaneously, and each was in a vehicle of their choosing, ranging from a heavy monster truck to a light and nippy buggy," explains Wilkinson, who is still visibly excited by the premise. "You were all placed in a huge bowl with a gigantic beach ball, and the aim was to score goals by being the person to knock the ball out of the bowl. We used a sit-down machine and a joystick to drive the vehicles, and all the while you need to be looking around you to find the ball and see who was about to ram you.

"Finally, we had a game that could only be played in a VR environment, and it was tremendous fun. It's such a shame that this wasn't the game that Virtuality began life with, because it might still be around today if it had." McIntyre was involved with another promising project which lamentably came too late - a VR interpretation of Namco's seminal Pac-Man. "We tested an unfinished version of the game at the nearby DeMontfort University," he remembers. "There was almost a riot. Students were queuing around the building at one point, which proves to me that it worked."

Sadly, by the time the 32-bit PlayStation and Sega Saturn arrived on the market, the writing was on the wall not only for Virtuality, but the concept of game-focused VR in general. "The firm's success was based on the shock and awe factor," explains McIntyre. "Up until that point users had only really experienced games which featured bitmap graphics, and to be immersed in a 3D world was fabulous. But the emergence of new console hardware was the death knell for Virtuality. The experience lost its novelty, its appeal and ultimately its USP."

After treading water for months, the company was finally declared insolvent in 1997, by which point the average gamer's interest in the tech had dwindled away to nothing. Players were being wowed by shiny new home consoles that supplied immersion without the need for a cumbersome, sweat-drenched headset. "I think Virtuality's biggest mistake was thinking that games were what was going to make the company successful," laments Wilkinson. "At that time, it was just never going to happen. VR was a gimmick that the company desperately tried to shoehorn a gaming experience on to."

Don't believe the hype

"It is well documented that if you over-hype a product and fail to deliver on the promise then the public will abandon you in droves," says Williams. "VR provided novelty value for the majority of arcades that deployed it, but an amusement venue cannot depend wholly on novelty; it demands a level of repeat visitation and no one wanted to play the original VR systems more than once. A level of unreliability, poor performance, substandard presentation, complicated operation - not to mention the discomfort of wearing an overly heavy head-mounted display - are just some of the litany of issues that plagued the early concept, and spelt its extinction as a viable platform. All this was not helped by manufacturers over-publicising their system's capabilities and ignoring their limitations."

The significant transition from 2D to 3D gaming in the mid '90s also stymied VR's chances. "The term 'virtual reality' became confused as a result," admits McIntyre, who now works as a Creative Technologist and gives lectures at Glasgow School of Art and Strathclyde University - the latter venue being where he obtained his MSc. "Many of the early 3D games - such as Doom, Duke Nukem, Heretic and Descent - all met the needs and imagination of users. 3D graphics and the entertainment software associated with it improved at a tremendous rate, and I think manufacturers felt that users could have an immersive 3D experience without actually being 'immersed' in the VR sense."

Despite fading from the public eye in the past decade, VR's influence can still be felt in gaming today. "The whole motion-tracking and motion capture explosion in consumer gaming, from the Wii to Kinect, can be traced back to the VR," says Williams. "If it were not for the need for sophisticated motion tracking technology back in the '90s, then we would not have seen the cost-reduced applications that have been integrated into these consoles today." VR-inspired devices are still being produced, too - the most recent being Sony's HMZ-T1 Personal 3D Viewer. "The HMZ-T1 is the latest recreation of the head-mounted display, though it is marketed as a personal viewer, rather than being a window on a virtual environment," continues Williams. "It looks remarkably similar to previous VR head-mounted display designs from the late '90s."

Virtual reality rebirth?

During Virtuality's short time in the spotlight, some industry analysts commented that VR gaming was ahead of its time. Given that display technology has improved to the point where ultra-lightweight glasses are available, and motion tracking - such as that offered by Microsoft's Kinect - neatly removes the need for awkward controllers, could VR possibly be due for a comeback? "For the majority of games in the market today, it would actually make things worse," Wilkinson grimly replies.

"Driving games might see some benefit, but in terms of first- or third-person games, a VR headset would be of no use whatsoever. I can imagine that some people will be utterly convinced that Call of Duty would be better if you had a headset on and were looking around you, but it wouldn't. It would be very frustrating and far more difficult to play. For one thing, you'd lose the 'aim down sights' feature; instead, you'd have to actually aim the gun yourself - not an easy thing to do with a headset on - which takes far longer than pressing a shoulder button and having the game snap the sights onto an enemy. Players would suddenly discover that they're not as good of a shot as they thought they were.

"There's another issue with set-pieces, which most modern games rely on these days. I can pretty much guarantee that well over 50 per cent of the players in a game using VR would be looking the wrong way when a spectacular set-piece happened. You can't force the player to look in a certain direction, because that breaks the immersion. For our oil rig simulation, we went to the expense of going to a special effects studio and have them blow stuff up for us, which we recorded and streamed onto textures in the game. It was pretty impressive, but the problem we faced was that a typical user would be busy examining a section of pipe by their foot instead of looking where we wanted them to."

It would appear that any potential VR revival faces the same kind of issues that Microsoft's Kinect has experienced over the past year or so; it would require software that is built around its own unique strengths, rather than traditional games that have been shoehorned into a new and largely incompatible interface. "Bolting VR onto existing games isn't likely to be much of a success," states Wilkinson, who clearly knows his stuff as he is now employed at Activision as senior director of technology. "VR games need to be their own genre, with their own gameplay mechanics that the head-tracking either makes possible or, at the very least, enhances. If the headset can't do either of those two things, it simply becomes a gimmick that will die out very quickly."

Williams has similar misgivings, but also feels that emerging ideas in the realm of interactive entertainment may mean that VR as we traditionally know it - bulky headsets and all - may not be resurrected at all. "Many things that could not have been achieved with the technology of the '90s are now possible," explains Williams, who runs The Stinger Report, an E-newsletter catering for the Digital Out-of-Home interactive entertainment sector.

"While head-mounted displays were once seen as the only way to represent a virtual environment, the latest projection systems boast surrounding visual capabilities that render a headset superfluous. These systems are the new generation of 'immersive capsule', and combine body tracking, non-glasses 3D and a level of fidelity through 4D - otherwise known as physical entrainment effects - that surpass what a home console can ever dream of offering. Systems such as these could herald the rebirth of immersive entertainment far more than the return of VR."

Several months after this article was published, Oculus Rift's Kickstarter raised $2,437,429 to fund the release of prototype development kits. Earlier this week, Sony unveiled Project Morpheus, a PlayStation VR headset that it hopes will herald a new era of gaming.