Redshirt review

Captain's blog.

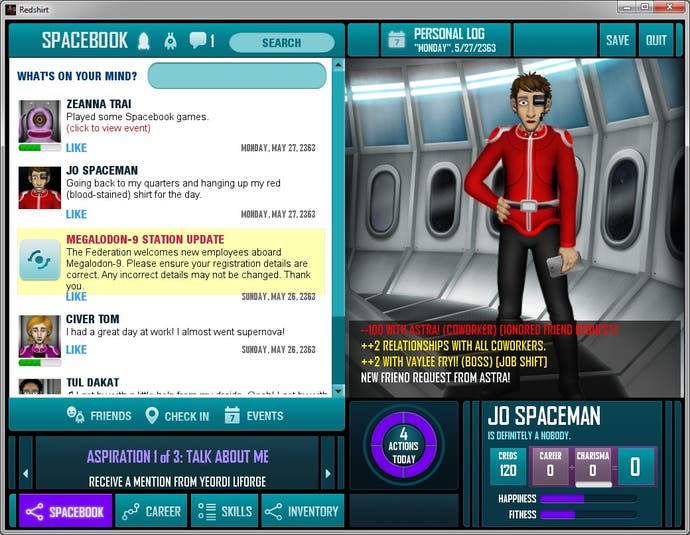

Jo Spaceman is depressed. Like, really depressed. Her happiness rating is at -100. This gloom isn't entirely a surprise. Not only has she just come out of a relationship, but she's also recently returned from a mission to an alien planet that resulted in the untimely death of several close friends. Oh, and she's also an Emoid, a species that has a natural tendency towards the morbid. Yet even by those standards, Jo is at rock bottom.

I decide that maybe it would help to share her feelings, via an update on her Spacebook profile. "Feeling strong enough to take on a Krongian today!" she gushes, rather unexpectedly.

This emotionally random outburst, sadly, illustrates the core problem with Redshirt, an otherwise ingenious combination of life simulator and sci-fi satire. Taking the role of a lowly bottom-rung employee on the Megalodon-9 space station, your goal is to ascend through the social order while maintaining health and happiness. The more successful and popular you are, the greater your chances are of escaping from the station before it's destroyed in an imminent catastrophe.

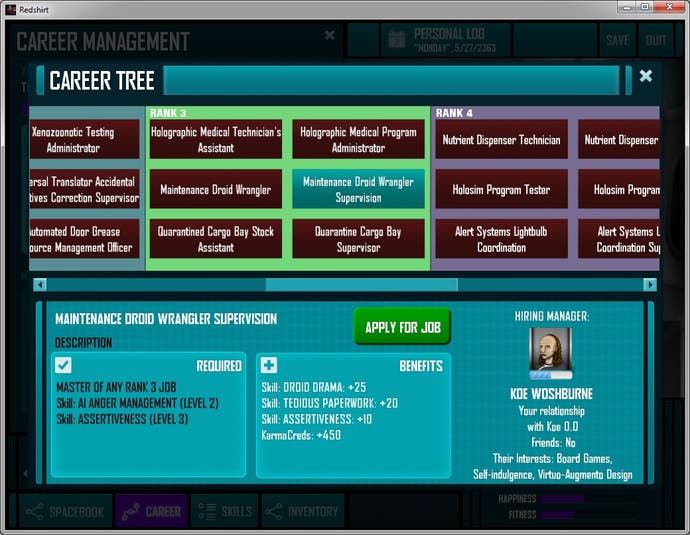

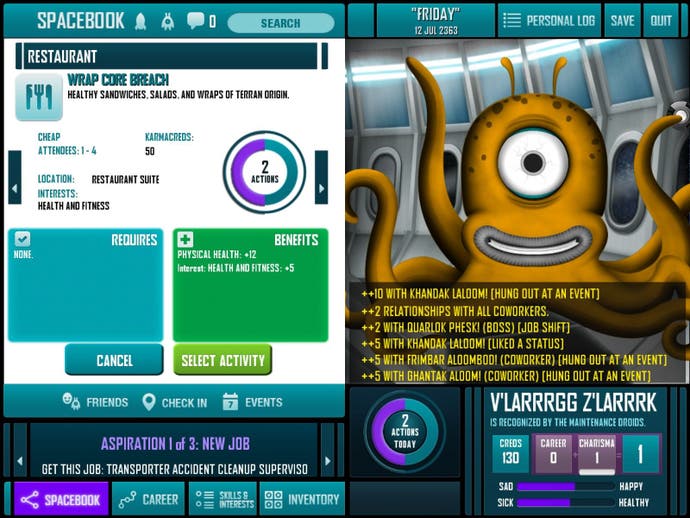

This task is accomplished through Spacebook, the station's social network, use of which is mandatory for all staff. Spacebook not only lets you make friends and send messages, but it's also where you'll organise events, do your shopping and plan your career. Each day you have a specific number of actions that can be performed - six seems to the maximum - with work and sleep as non-negotiable interruptions along the way. Posting a simple update or 'liking' someone else's post takes up one action. Going out for a meal or some other social occasion uses more.

"It's an ambitiously ingenious concept."

It's an ambitiously ingenious concept, and the game is witty enough to suggest it might actually be able to pull it off. The skills you can build up to aid your career come under fun categories such as "schmoozing" and "pandering to authority", and there's a strong seam of satire aimed at both the more arcane corners of sci-fi fandom as well as the meaningless management-speak of the corporate world.

To begin with, Redshirt's world is strongly defined and compelling to poke around in, even through the limited and somewhat garbled interface that Spacebook offers. It doesn't take long for the boundaries to close in, however. This is as indie as games get, and it quickly becomes clear that the ideas far outstrip the resources available.

For a game that is almost entirely driven by text, there's an unforgivable amount of repetition. The same randomly generated updates fill your in-game news feed, with different characters even posting the same phrases right after each other. Your own updates are completely out of your hands, meanwhile, with icons that automatically generate an update for you. You can opt to say something positive or negative about your job, but must then scroll through your virtual wall to find out what you just posted.

You can also send direct messages to your friends and co-workers, but only from a handful of stock sentences that must be stuck together, Madlibs-style. There are only three choices for each line of your message, meaning your interaction with the world and the people who inhabit it is always maddeningly abstract. At no point do you feel like you're engaged with an actual social network.

The reason is pretty clear: simulating realistic interactions is incredibly hard. To play as intended, Redshirt would have to pass the Turing Test dozens of times over, and that's clearly not going to happen. Instead, you're left to project personalities and consistent emotional states onto characters that are frustratingly hard to pin down from one turn to the next. A character may ask to start a relationship, only to dump you in the next turn. Or they may nag you in messages to spend time with them, when you've just been to a restaurant together. When they do turn against you, it's impossible to work out why, or how you're supposed to win them back over.

It's tempting, at first, to imagine that this mercurial nature is some sort of commentary on the shallowness of social networking, but as the turns tick by and you find yourself clicking on things at random, unsure as to what impact you're having, it's hard to avoid the realisation that the game has simply bitten off more than it can chew.

"It's hard to avoid the realisation that the game has simply bitten off more than it can chew."

Not that it's worth getting too attached to any of the characters anyway, since at any point you can be summoned to take part in an away mission, where you're reminded of the short life expectancy of the titular redshirts. It seems to be impossible for the player character to die during these expeditions, but you will see characters you've worked hard to butter up and romance wiped out in the blink of an eye, plunging your avatar into a spiral of depression. As with too many other features, there doesn't seem to be any trigger for these events, nor any way to impact the outcome. That works as a wry statement on the cavalier body counts of supporting players on sci-fi TV shows, but makes for a very irritating gameplay feature.

In the end, Jo Spaceman's tenure on Megalodon-9 came to an abrupt and rather anti-climactic end. After discovering I could buy a shuttle ticket to freedom for 30,000 credits, I set about saving up the required amount. Then, out of the blue, I was offered the chance to buy a ticket for 5000. Which I did. Game over. I'd won, apparently, with almost 100 in-game days still on the clock.

It's easy to admire what Redshirt is trying to do, and at a surface level it gets a lot right. Science fiction fans will love the genuinely funny writing, which is crammed with in-jokes and solid satirical jabs, and there's amusement to be had in the early going as you first explore this odd little universe. It's a game you want to like.

The game just can't sustain or build on its core ideas, though, because to do so would require a feat of programming that would likely be beyond even the most advanced AI engineers on the planet. A game like this needs to simulate dozens of reasonably realistic personalities at the same time, while allowing the player to interact with them in myriad ways.

For all its charm and ambition, Redshirt can't even come close to realising that goal, and inevitably ends up as a fairly flat and repetitive exercise in meaningless random text and mindless icon clicking. In that sense, it's arguably a perfect simulation of real-life social media, but it unfortunately doesn't make for an edifying game experience.