Resident Evil Zero review

Murder on the Disorient Express.

It's an ignoble death for the passengers of the Ecliptic Express as their train and, soon enough, their brains are breached by a plague of leeches. Still, there are less distinguished surroundings in which to die. Resident Evil has always presented a hotchpotch of locales in its jittery tour of Victorian mansions, small town American police stations, industrial factories and Renaissance churches. The Ecliptic Express, however, with its pre-war luxury - the feathery lampshades, the forest of mahogany, the tinkling bottles of Scotch - is new, a scene that could have been lifted from any number of Agatha Christie novels. Puking zombies aside, it's a delightful place to be.

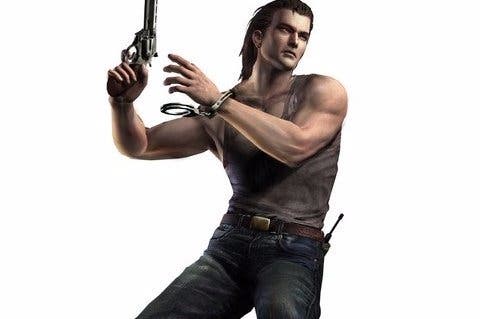

The nostalgia comes in two hits. There's the familiar ambiance of the murder mystery-cum-buddy movie, which follows rookie cop, Becky, and a haggard convict, Billy, as they work together through and, eventually, out of disaster. And then there's the style: the polygonal characters placed amidst detailed static backdrops, like dolls in front of a fine painting. Pixel art has been mined to the point it no longer has a wistful effect. Here, by contrast, is a rare jolt of graphical nostalgia, heightened by the fact that the style, favoured by so many games between 1995 and the turn of the century, has never looked quite this good. Character models bed into the backdrops, which fizz with incidental animations - the frantic bubbles of a panoramic fish tank, for example, or the lazy chopper blade of a ceiling fan. This remake, with its widescreen rendering and dynamic lighting is, exquisite.

Elsewhere, Zero is typical of early-era Resident Evil. There are the grumbling zombies, the obnoxious crows and those intrepid, window-shattering Doberman, so desperately in need of a hanky. There are the bosses (usually overgrown creatures such as giant bats, spiders and centipedes), which soak up your valuable ammunition and, with every swipe, infect your character with a limp that can be fixed by eating a fistful of coriander, naturally. There are the knotted buildings with their insanity layouts: locks that require a lit candle, or the correct time to be set on a grandfather clock or, more weirdly still, a leech to be pressed into the relevant indentation. There are the ponderous door animations, those intermissions that once covered load times as you moved from one room to the next but now exist merely to provide a rhythmic ramping of tension. And there are the safe rooms, with their comforting lullabies and progress-saving typewriters. Finally, there is the enduring question of luggage.

About a third of your time will be spent managing your excruciatingly limited inventory, now split between two characters, who are only able to swap items while standing next to one another. You'll need to ensure that ammunition goes to the character holding the relevant weapon, and, as only Becky is able to combine herbs into more powerful powders (freeing up a valuable slot in the inventory) every glinting object carries with it the gravity of consequence. It's a minor joy every time the game tells you you're able to discard a key. Often you end up littering the floor with precious items that you simply cannot accommodate.

Billy and Rebecca are hardly Resident Evil's most striking characters, but the bond they build through the course of this meandering adventure is nevertheless strong and memorable. This is, in the main, a function of the game design, which enables you to switch control between the two in order to solve its puzzles. Capcom's designers make full use of the conceit. They gleefully force the couple apart and invent ever more convoluted ways that they are able to send one another key items. There's a certain degree of ingenuity involved, but the pay-off when you finally ensure the correct items reach the correct destination is rarely worth the pain.

Every Resident Evil game is an intricate contraption, a series of nested puzzles that require concerted busywork as you find the relevant lock (be it literal or metaphorical) and then hunt for the appropriate key. The game assumes its own weird logic in which such tasks and distractions begin to seem reasonable. In the game's final stages, when the designers make their tallest demands (mix the chemicals in order to create acid to power a battery, to operate machinery, to enable you to collect a key-card from a ledge) you've become so inured to the nonsense it feels reasonable. No audience would stand for such obscurity in the context of a film or novel, but set within the context of a video game, where we are used to our progress being impeded and gated in mysterious and often-preposterous ways, it somehow works.

For contemporary players there are the usual mundane complaints from early-era Resident Evil games. It's difficult to pick up items unless you're positioned in exactly the right spot, a task made all the more irksome when interactive objects are clustered together. The notorious control scheme (albeit improved greatly here) adds the wrong sort of terror to encounters with zombies. So too does the crude aiming scheme - although, arguably, anything more sophisticated would be unworkable thanks to the game's wayward camera angles. The b-movie dialogue is devoid of subtlety. Then there's the numbing predictability of the jump scares: every time you pass a body slumped seemingly boneless against a wall, you can be sure it'll groan to life next time you come by.

Other than its delightful new lighting and pin-sharp textures, the re-master's most substantial addition, Wesker Mode, is only accessible when you complete the game. This allows you to play as the titular Wesker in place of Billy (although Billy still acts in the game's movie scenes). The character has a different set of abilities including Shadow Dash, which allows him to dart forward in a skidding lunge, and Death Stare, a long distance attack. It's silly, knockabout fun, but will surely only attract the most devoted fans as, for most players, a single run through the game will be quite enough.

This leads to the question of for whom this re-master is for, exactly. By 2003 Resident Evil was an acquired taste. Today this style of game design has vanished. In part, that's because the tangled, repetitive design was probably too divisive to sustain a sufficient audience. It's still possible to perceive, however, the kernel of the series' early, glimmering appeal, which made the games such notable peaks in the medium's landscape for a time. Of all the early Resident Evil games, there is none better to showcase its idiosyncratic charm than this one, an accolade owed to the ingenuity of its dual-protagonist design, and the melancholic allure of its forsaken locales.