Retrospective: Daikatana

Not-so-heavenly sword.

It was gaming's big millennium flop. John Romero, respected around the industry for his pioneering work on Doom and Quake, promised the world that he'd make it his bitch. Huge advertising campaigns, giddy first-look previews and excitable chatter spread around magazines, websites and message boards. Just how good would this newly announced shooter from awesome upstart developer Ion Storm be? In the wake of the frenzy, there seemed to be only two options - it would either be earth shattering or merely amazing.

Ion Storm was co-founded by Romero in 1997, along with former id Software creative director Tom Hall. It consisted of two studios: as Romero's Dallas team knuckled down to work on the super-hyped Daikatana, a sister office in neighbouring Austin scurried away in the background on its own game - one with a somewhat lower profile.

Eyebrows soon rose, though, and before long Daikatana's initial hype turned into concern. The game was repeatedly delayed, and Romero's rockstar public image wasn't doing him any favours. In April 2000, the team finally unleashed its baby into the wild. The gaming press was unanimous in its verdict, and in posing the same big question: just what were Ion Storm Dallas thinking?

A few months later, the Austin studio would release its own game, one that many would herald as the greatest PC game ever made. In the aftermath, it was understandably Deus Ex that received the magazine space, the features and awards and big-budget sequels. Its legacy grew and grew, while that of Daikatana fizzled out into nothing more than an industry-wide joke. 'Hey,' people would say, comforting themselves after dropping £35 on a sub-par computer game, 'At least it's not as bad as Daikatana.'

In reality, the legend of Daikatana paints it as a far more joyless game than it was. Released to middling rather than atrocious reviews, it fell victim to the hype machine more than anything else. It was a frequently miserable, turgid, over-long and frustrating shooter, but the gaming world has seen far worse, and its failures were often so surreal as to be brilliant.

Its biggest mistake, perhaps, was shooting for ambition in all the wrong places. When development began in 1997, Quake was the height of FPS gaming. Daikatana was to take its episodic structure and turn it into something epic: a globetrotting adventure of big bullets and whopping great robots, of time-travel and magical weaponry, in a universe that skipped between far-future Japan, ancient Greece, dark ages Norway, and a San Francisco of not far beyond the present day.

Add to that AI-controlled sidekicks with whom you had to co-operate in order to complete certain sections of the game and a dramatic story about an evil corporate overlord and a devastating global pandemic, and Ion Storm thought they were sitting on the recipe for success. There was just one problem: in the late '90s, the games industry moved fast.

After originally opting to use Quake's engine, Ion Storm ported the game to its sequel's tech - a partial cause of the delays. But it was still a short-sighted move. By the end of 1998, Half-Life had already bettered its graphical capabilities, and erased many of its technical limitations - not to mention revolutionizing how first-person shooters were designed. Two years later, Quake II and its engine were practically obsolete.

A return to the game now is ripe with opportunities for a laugh. Take the opening cut-scene as a prime example. Cameras swing and pan around huge mountaintops... constructed of about four polygons and plastered with low-definition textures. Majestic battles take place there... but the animations make it look like the characters are doing the robot rather than fighting for their lives.

Most absurdly, NPCs exchange lengthy, dramatic streams of dialogue, gesticulating wildly, their heads flailing to and fro while their lips, hilariously, remain zipped shut. Returning to Daikatana now unearths something quite ridiculous, but it was even something of a laughing stock back in 2000, by which time videogame animation had progressed a lot further.

Still, it's because of this ferocious, unintentional silliness that I continue to have a real soft spot for Daikatana. Even now - perhaps especially now - its flaws meld together into a bizarre B-movie of a game, one that flails wildly as it grasps at a hundred ideas that were always going to be beyond its reach. It's enormously frustrating, but still oddly playable, and it's fascinating to see Ion Storm's ambitions collapse under the strain of ageing technology and incomplete design. Somehow, for all its problems, Daikatana had something that so many shooters struggle to find: a personality.

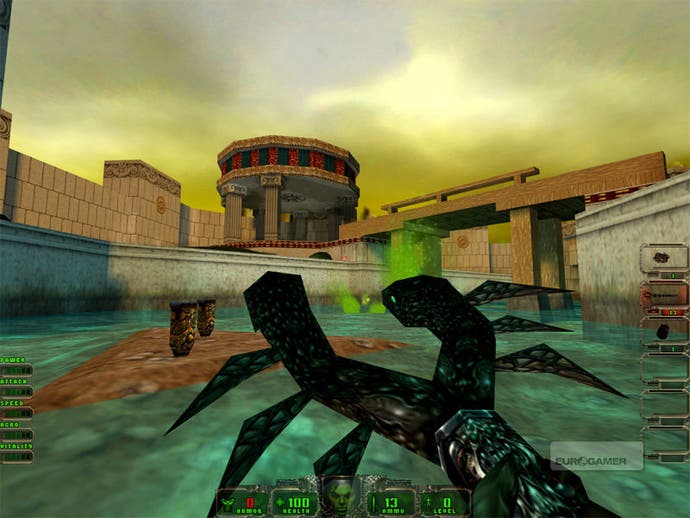

The game begins in a Kyoto swamp. You can imagine how the design document might have called for a huge, vividly colourful expanse of soggy land and toxic waters. Of course, the engine couldn't handle that, so what's left is a medium-sized room with a skybox, and a level that quickly finds a way of dragging you into the city's sewers. Yes, Daikatana begins with a sewer section. It might as well have started you off in the middle of a giant crate.

It's also a game with hideous AI, whose only setting seems to be 'charge at player until someone is dead'. It gets around this by populating half of its world with enemies whose goal is to charge at you until someone is dead. In the swamp, this means robotic mosquitoes: perhaps the most beautifully irritating videogame enemy there has ever been.

I love the mosquitoes. They're awful. They swarm, target you, and start prodding you in the face as your character emits the most unlikely of agonised screams. At the start of the game they're bloody everywhere, and every single one seems to be trying to annoy you to death. But when I'm not dying, I'm laughing.

Before too long, the game's found a way to introduce a pair of other characters, to whom you can issue light commands to help you in puzzles or in battle. A great idea in theory, and one that we've seen employed to great effect in the time since.

But in Daikatana, they're everything you'd hope they wouldn't be. Your partners ignore you. They get stuck in doorways. Sometimes, one of them will absolutely refuse to pick up a health pack, or stand directly in your line of fire, and die, which means game over. It's absolutely ridiculous. And also absolutely hilarious.

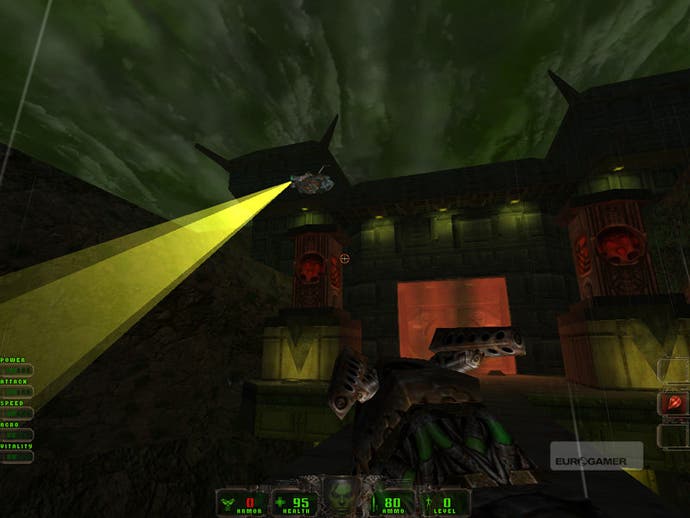

Then there's the huge canon of weaponry, which clearly strives so hard to avoid FPS convention but still manages to fall into the same traps as every rubbish videogame gun. Among your ever-changing arsenal are giant maces and venomous snakes, but almost everything is underpowered to the point where you might as well be wielding an inflatable hammer. One of Daikatana's most ingenious inventions is the first weapon you'll come across: a gun whose energy charge you can bounce off walls, but which in these closed-off environments usually does more damage to you than it does your enemies.

This is a rare breed of game: one that got so caught up in its own bigger picture, in its majestic sense of adventure and its individual design ideas, that it fluffed the basics quite spectacularly and failed to examine what other games were doing. Daikatana's biggest ideas simply didn't work, and those beneath them felt like an ode to first-person shooter cliché. It was both ahead of its time and stuck in the past.

It's not all bad, though. Beyond the atrocious opening chapter, the level design grows smarter and more involved, and the environments - while poorly rendered - become more evocative. The buddy system occasionally strays dangerously close to working, and some of those silly weapons are strangely satisfying to wield. Daikatana was never dreadful. It just made some pretty dreadful mistakes for a game that claimed it would make us all its bitch.

Crucially, some of those bizarre, bumbling missteps still raise a smile. The ridiculous enemies, with names like Thunderskeet and Robocroc. The absurd saving system that sees you fighting the same enemies again and again (you collect 'save gems', and on the hardest difficulty setting there's only one per huge level). The clumsiness of the AI, the hilarious voice acting, and the mountains of genre tropes that fill the gaps wherever a big idea couldn't be fulfilled.

No one could ever say that Daikatana was a good game. It was a cataclysmic failure for Ion Storm, years of development and marketing and celebrity poured into a sub-par experience that became a running joke. But I'm glad it exists. Had it been anything other than what it was, I don't think I'd look upon it so fondly.