Retrospective: Grand Theft Auto 4

Prior convictions.

I'm back in Liberty City again. It doesn't feel like five years since Grand Theft Auto 4, but while other games have been traded in or loaned out, that disc has remained beneath the TV, a passport waiting to be used.

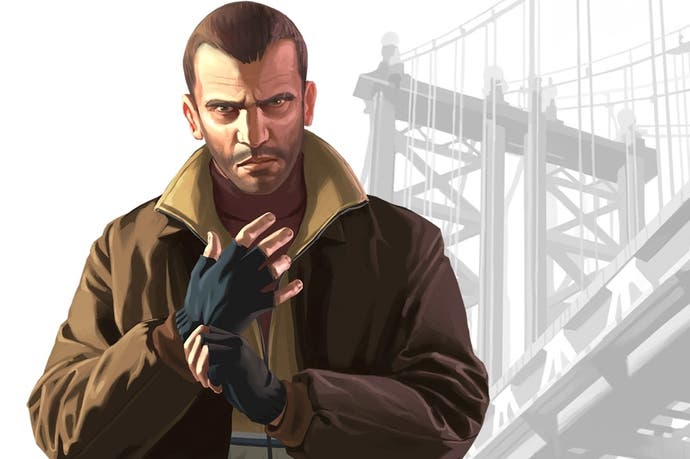

I'm back in Liberty City again, and I'm amazed at how tangible it is. I've mostly forgotten where things are, but I've not forgotten how it feels to walk these streets in Niko Bellic's scuffed shoes. This, I think, is the Rockstar difference. Plenty of other openworld games present you with a city, but none go to such lengths to make it feel like a place. I start a new game, but immediately ignore the mission marker that will lead me to Roman and the start of the game proper. Instead, I just walk. Ambling through neighbourhoods, drinking in the sights as dawn breaks over Liberty.

At an intersection, a car narrowly misses me as I cross the street. I stop and glare. The car stops and the driver gets out, all bravado and threats. I'm about to square up to him, when I notice a cop car waiting at the lights. I turn and walk away, stop at the corner and watch as the jerk gets back in his car and drives off. Niko rubs his close-cropped hair pensively. A scruffy-looking guy shuffles past, eating a hot dog. He looks homeless. Frankly, so does Niko. Time for breakfast.

I'm back in Liberty City again, and all of this all happens within minutes of setting foot on the street for the first time. It's not the most gripping story ever told, but it is a story, and one that emerged naturally from Liberty's grimy milieu. This is how Grand Theft Auto 4 impresses - not with the big showy missions or outrageously wacky stunts, but with a quiet procession of interactions that combine to form an experience that is richer and deeper than those offered by its peers.

For openworld games, I've come to realise, it's a constant battle between content and context. Missions tend to boil down to "go to this place and shoot people and/or collect something" so what makes the difference is the context the game world places around those actions. In the early GTA games, that context was one of cartoonish transgression - the thrill of being the guy who skids into a line of Hare Krishna, who fires a rocket launcher at a police helicopter, who takes a tank for a spin along the Miami coastline.

Grand Theft Auto 4 offers a different kind of context. Yes, those surface thrills are still there - if muted slightly by the game's melancholy undercurrents. The game is still incredibly funny, just in a more deadpan way than previous titles. But the greater realism of Liberty City, the mournful arc of Niko and his ill-fated attempt to leave violence behind, all add a more interesting texture - a richer context - to what would otherwise be simple tasks.

The most potent example, for me, is Have A Heart, the 34th story mission of the game. Niko is working for drug queenpin Elizabeta Torres, and with one of her bodyguards in custody about to turn state's evidence, she's on a hair trigger. Enter Manny Escuela, a fellow Puerto Rican immigrant and ex-con, who has turned his back on crime to become a crusader for inner-city peace. To this end, he's making a documentary and turns up in Elizabeta's apartment with cameraman Jay for an interview. In her paranoid state, Elizabeta shoots them both dead.

It's a twist that I should have seen coming. It's certainly nothing particularly surprising, given GTA's history of sudden violence and disposable supporting characters, yet for some reason this one really caught me off-guard. Maybe it's because I liked Manny. He was an idiot and a blowhard - claiming at one point to have invented rap music - but also a rare glimpse of hope and redemption in an otherwise murky tale.

And now I'm responsible for disposing of his body - and that of Jay, his cameraman. The mission is, in terms of mechanics, ridiculously basic. Drive from the apartment to a doctor's office, and offload the corpses without alerting the cops. It's as simple as openworld mission design gets - an A to B journey where the only complications are the ones you make for yourself through recklessness.

Yet this mission really stuck with me. Why? Context. I'd just seen two men shot dead. Their bodies were right behind me, in the trunk of the car. Call it a moment of clarity. Taken together, the simplicity of the task and the richness of the world allowed me the space and perspective to really consider what Niko - and by extension myself - were doing. If I'd had to run 10 roadblocks and shoot 50 more cops to get there, that realisation would have been lost in the noise.

It's true that GTA 4 suffers from some of the worst narrative dissonance of the series, and that's entirely down to this depth. In terms of bodycount, Niko would be one of most notorious killers in American history - hunted down by the FBI long before the end of the game. That disconnect between the wanton bloodshed demanded by games design and the more human tale Rockstar is trying to tell is what makes GTA 4 so interesting to me.

Of course, not everybody sees it that way. The backlash was as inevitable as it was vocal, as contrarians lined up to let the world know that they weren't impressed by Rockstar's newfound maturity. Where was the silliness? Where was the fun?

Such complaints are understandable, but also misguided. Grand Theft Auto 4 shows growth. Not just the technical improvement the industry expects and demands, but actual artistic evolution, a willingness to explore more challenging emotional terrain without offering the comfortable refuge of cartoon irony. It doesn't always pull it off, but it succeeds as much as it fails and for that I'm glad.

Writing off GTA 4 as the "boring" openworld crime game is like wishing the Beastie Boys had continued making dumb party rhymes rather than reaching out and creating Paul's Boutique. It's like wishing Tarantino had kept remaking Reservoir Dogs, rather than stretching himself with the soulful middle-aged paean of Jackie Brown. We need to change in order to grow. That's not only Niko's journey, it's the journey of Grand Theft Auto itself. Here's to the next chapter.