Retrospective: Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas

How Rockstar's ambitious ghetto fable captures a blockbuster series in mid-evolution.

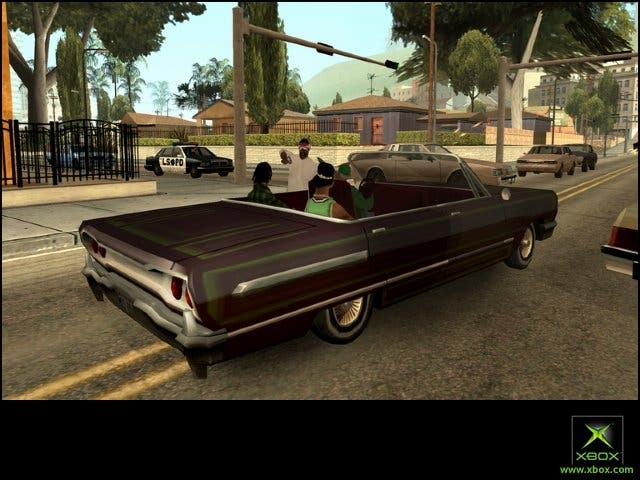

It starts with that high-pitched G-funk siren wail. Even before you've set foot on the streets of Los Santos, Rockstar's obsessive attention to cultural detail has already got you in a West Coast frame of mind, a world of sneaker-clad feet squeaking on tarmac as they run from the five-oh; of helicopters in the night and the snap, crackle and pop of distant gunshots; of sipping a forty with friends, waiting for the noon heat haze to lift.

Like the previous Grand Theft Auto games, San Andreas is a cartoon version of a world filtered through pop media. It's just that where Vice City splashed around in the garish neon-pink world of Miami Vice and MTV, a fantasy within a fantasy, San Andreas starts from a more tangible real-world source. The South Central projects immortalised on wax by NWA and Ice T may be exaggerated, but they existed - and still exist.

It's fitting that these mid-period GTA games took their titles from the cities they created. Although it may be CJ Johnson's story, it's San Andreas itself that draws us in. Stepping back into his world eight years later, I'm struck by how real it still feels. Gaming has offered up dozens of urban sandboxes since 2004, but few match - or even understand - what Rockstar brings to the table. Lots of rivals copied the Theft and the Auto, but missed out the Grand. There's a reason why architectural trade magazine Blueprint chose to profile Rockstar as a pioneer of virtual urban design.

The characters are boxy, the textures crude and the draw distance is often shocking, but there's a sense of place that still impresses. Even more so when you consider the sheer scale and ambition of what Rockstar attempted with San Andreas. With competitors snapping at their heels, clearly there was a need to keep forging ahead, pushing back the boundaries of the sandbox to see how much world we could take.

From those early missions in the neighbourhoods of Los Santos, San Andreas widens the scope to draw in the rest of that city, then keeps going. Vast tracts of countryside, hills and forests surround the looming bulk of Mount Chiliad. Then comes San Fierro, the city by the bay, and deeper still into the game you can head to Las Venturas, the gambling mecca in the desert. Each is its own place, with its own feel. And that's crucial. These are places that you can feel, more than just rearranged assets or a new gameplay stage. The devil is in the details, and Rockstar's intricate web makes these cities feel lived in, as if they were always there, not just conjured up from ones and zeroes stored on a disc.

In hindsight, however, there's a sense that San Andreas saw Rockstar doing too much. This is a game that sprawls, both geographically and narratively, and CJ often gets lost against such a vast backdrop. In that sense, knowing what came next with GTA 4, it's easier to see where Rockstar's experiments were leading.

Not least with CJ himself, who marks a definite break from the traditional Grand Theft Auto protagonist. Both Claude, the mute thug of GTA 3, and Tommy Vercetti, the larger than life career criminal of Vice City, were purposefully amoral cartoons. They existed mostly as a gateway avatar, giving the player tacit permission to live out their own vicarious fantasies, rather than compelling characters with unique tales to tell.

CJ isn't like that. He has depth and conflict, soul even. Forged in tragedy, and forced to compromise his own sense of honour by cruel circumstances, he's very much the forerunner of Niko Bellic. Neither character feels like the sort to launch a rocket launcher rampage in a crowded shopping mall. The very thing that once defined the GTA series was suddenly rendered uncomfortable and weird by the power of good writing.

Yet the rampages are still there, along with a bunch of other wacky distractions. That same depth of character is what makes San Andreas such an incongruous experience. One moment CJ is a tragic figure, sucked back into a toxic lifestyle by personal trauma, the next he's flying a jetpack off Chiliad's peak, chasing Bigfoot in the forests or hijacking a combine harvester for no reason. The intimate world of the character grinds against the lunacy of the wider game world, creating a distracting narrative dissonance.

As great as San Andreas is as a pure gameplay experience - even allowing for the lumpy checkpointing and stiff control - it's a deeply weird game, as if somebody took Boyz n the Hood and randomly spliced in reels from various James Bond movies and episodes of Jackass. Rockstar was clearly aware of this curious contradiction, leading to the tighter focus and greater narrative depth of GTA 4. Gone were the wacky vehicles and more outlandish distractions, and in came Niko's mournful immigrant saga.

To play San Andreas in 2012 is to see Grand Theft Auto in transition, struggling to find a way to bridge the gap between the knockabout stunts of old and the more high-minded ambitions the studio had for the sandbox format. The ridiculous Hot Coffee scandal, in which an excised sex mini-game was found amidst the unused files on the PC disc, actually showed that Rockstar was growing up and moving away from adolescent concerns.

Red Dead Redemption showed that the studio has mastered the art of tying a vast landscape to a personal story without breaking the mood with silliness, and if GTA 4 represented the series reining in some of the wider excesses of San Andreas, what does that mean for the upcoming GTA 5, which finds an older and clearly wiser Rockstar returning to its west coast playground? At the very least, it would be nice to drop in on CJ, to see if he's grown up as well.