Retrospective: Okami

Dog day afternoon.

From StarTropics to Star Fox Adventures, many a Zelda clone has aimed for the stars. But only one brought the stars to us. Quite literally, in fact.

In Okami's opening moments our canine sun goddess Amaterasu summons a dragon deity in the form of a constellation by filling in the missing star with her 'celestial brush'. This godly device allows players to manipulate the environment and manifest objects. Fancy changing the time? Draw a sun or moon in the sky to switch between day and night. Want to blow up a cracked wall? Paint a cherry bomb beside it. Need to traverse hazardous liquid? Create a lily pad as a makeshift raft, then scribble a gust of wind for a gentle push.

It's impossible to ignore that all of these items and abilities were ripped straight from Nintendo's flagship series, but the difference is in their implementation. The magical effects of Link's ocarina or wind baton bare no sensible correlation to the player's interaction. You'd play a ditty, watch a cutscene, then poof - wind! Drawing with the celestial brush is a more tactile action and the results correspond directly with your input. This is one of those grand ideas, deserving to be as revered as Portal's titular gun.

Using the celestial brush is also much faster than Zelda's alternatives (although Skyward Sword's elegant radial menu pushed Nintendo's series a step in the right direction). Rather than pause, pull up a menu and painstakingly select an object or constantly reassign hotkeys, you tap one shoulder button to transform the scenery into a sepia-toned sheet of rice paper, then draw in the desired object or environmental effect. At face value this cut down time spent in menus. More importantly, it made you feel like an all powerful, rejuvenating goddess.

This is one area where Okami differed from its Hylian inspiration. You're not just saving a world; you're building it. Teasing trees into bloom, instigating gusts of wind and filling in bridges lends to the feeling that you're in control of this universe. It's not as open-ended as something like Scribblenauts, but it's remarkably consistent and functions near perfectly.

Years later Epic Mickey would borrow this concept of altering a painted environment with a magic brush, only it missed one key aspect. In Warren Spector's Disney tribute, areas would revert back to their original state upon being revisited - all of which made your impact on the world feel hollow.

Okami had more permanence. While chopped down trees would inexplicably reappear moments later, your positive influences on the world would remain throughout the entire game. The landscape you navigate at the end of the game is drastically different than the one you first encountered. That visual sense of progression is still lost in most open-world games to this day, wherein you merely trot back and forth through the same static terrain for hours on end.

Outside of the hugely inventive celestial brush, Okami's smooth controls surpass its green-garbed forebear. As much as I love Zelda, I could never entirely get behind Link not being able to manually jump. Pulling himself up a ledge or taking the long way around a ramp was just annoying enough to grate.

Amaterasu, however, does more than jump; she can double jump too. As Kieron Gillen so eloquently put it, "[double jumping] automatically improves anything." In the time since Okami's release Link has transformed into the teen wolf of Hyrule and gained a stamina meter for sprinting, but neither of these compared to Amaterasu lupine athleticism. Where Link's newest incarnation gets winded after a 100-metre dash, Amaterasu's speed only increases as she runs. Okami's rendition of feudal Japan is a large one and warp points are sparse, yet backtracking seldom feels like a chore due to such swift scurrying.

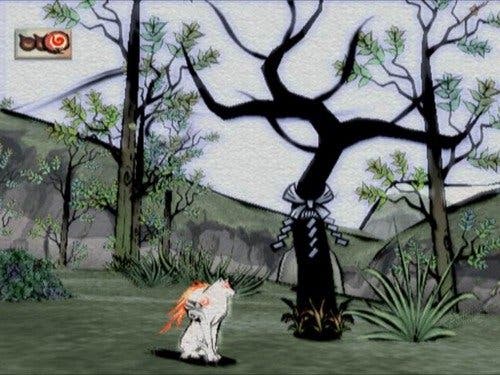

Even more astonishing than Okami's streamlined sensibilities is its striking art-style, a collision of watercolours, pastels and rice paper. For my money, no game since has been able to replicate Okami's pristine beauty, though El Shaddai, helmed by Okami's visual director Takeyasu Sawaki, came close. The splendid visual design isn't just for show either, as it's consistent with the premise of a celestial goddess maintaining control of the earth through art. (It's worth noting that the Wii version of Okami over-saturates the colour palette and downplays the parchment texture filter, making everything look glossier. While its richer colours look good in their own right, the Wii version reminds me of when George Lucas renovated the Star Wars trilogy, and I prefer the PS2 original's washed out look.)

While I'm as sick of anyone of the "are games art?" debate, Okami is clearly a game about art and its importance. In its bizarre logic, painting makes trees bloom, bridges form, and time slow down. The well-developed right-hand side of Okami's brain recognizes the importance of all art, not just painting. In an early scene a wise old man dances to summon the sun. In actuality it's Amaterasu and the player who pull the strings, but the old man thinks it's his dancing and that's what's important.

This difference of perception between the NPCs and the player is crucial. When we look at Amaterasu we see a fantastical being; a wolf adorned with tribal tattoos, spinning rosaries, and a brush in her tail. Every so often we see her from an NPC's point of view revealing her to be just a regular white wolf. By casting the player as an animal it wisely circumvents the silent protagonist conundrum. It's almost comical when Link goes for the silent treatment as his girlfriend bids him farewell at the beginning of Ocarina of Time. Amaterasu's one-sided conversations feel natural in comparison.

Much of this is due to its delightful cast of well-drawn (no pun intended) characters. Over the course of Okami's long and winding campaign, these NPCs develop and grow. Your sidekick Issun, a fairy-like miniature 'wandering artist', starts off an obnoxious chauvinist clown, but he matures significantly throughout the game (even if he still talks too much). Elsewhere, a cowardly drunk descended from a mighty hero is plagued by regret for a grievous mistake. Once his shame is revealed his drinking becomes a lot less comical. A scene where a bamboo salesman bids his granddaughter farewell is as nearly as moving as anything that's come out of Pixar.

So is Okami better than Zelda? I'm not so sure. In terms of control and visuals it leaves Link's adventures in the dust. However, there are some serious issues holding Okami back; chief among them being that 90 per cent of its collectibles are completely and utterly useless. Most are merely treasure that serves no purpose but to be sold off, yet there's seldom anything expensive worth buying. The rest of the items help in battle, but combat is so easy anyway that you'll barely need these. Also, I know Amaterasu's a dog and all, but even they can only play fetch so much before getting tired - and the proliferation of Okami's fetch-quests soon becomes a chore.

In terms of design, Zelda is still tighter and more efficient with sharper puzzles and more tightly conceived dungeons. But Okami succeeds its obvious inspiration in nearly every other way.

If the point of games is to transport us to another world or instill a sense of omnipotence, then Okami is winner. Its painterly aesthetic is more dazzling than the cel-shading employed by Wind Waker or Skyward Sword (despite the latter being half a decade newer on better hardware), the controls more responsive and empowering, and the script more sophisticated. Okami may not get the better of Zelda on the whole, but it shines just as brightly.