Retrospective: Phil Harrison

Reflecting on Harrison's 15-year career at Sony.

Once the PS3 had launched and some - although not all - of the hardware questions were settled, Harrison could at least fall back on doing what he did best - software. His presentations no longer carried any hint of target renders or question marks over the abilities of the console. Instead, he has been responsible in no small part for rekindling interest in a console whose thunder, among hardcore fans, had been stolen by Microsoft - and while the PS3's software promise is still only partially fulfilled, Harrison's unveiling of titles such as Home and LittleBigPlanet have played a major role in igniting interest since the launch of the hardware.

However, recent months and years have also revealed a divide between Harrison and his compatriots at Sony - a divide which may have been even wider than the gulf which separates his measured, British presentations from their bombastic, immodest proclamations.

This is a divide which has its roots back in 2003, when Harrison really made his debut at Sony's E3 conference - not leading the presentation, a task which fell to Kaz Hirai, but as the executive whose backing had kept the green light lit for an intriguing new concept called Eye Toy.

Keeping Social

Eye Toy was the first of a series of concepts to emerge from SCEE's development offices (and their close third-party partners) which, slowly but surely, began to reinvent the PlayStation as a casual, social device that could be the life and soul of a party, rather than being a solitary, anti-social pursuit. While Microsoft chased the idea of playing together online, SCEE's development efforts went into getting people to play together on the same sofa, in the same living room, and with the whole household involved.

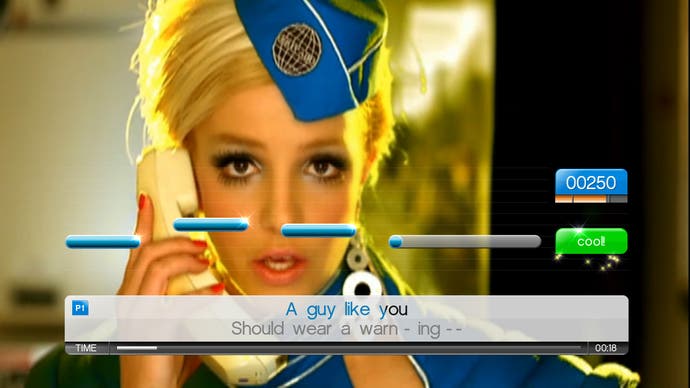

Although Kaz Hirai expressed great enthusiasm for Eye Toy on stage at E3 2003, however, the rest of Sony never quite understood the great social gaming experiment being undertaken at SCEE. Singstar followed Eye Toy, and quiz game Buzz followed Singstar - and in Europe, at least, incredibly strong sales of PlayStation 2 hardware and software, even late into the life of the console, followed those franchises. Just as Sony had reinvented the public perception of gaming when it put Tekken and WipEout into night clubs in the mid-nineties, so too did it reinvent public perception by putting Singstar and Buzz into living rooms across Europe.

Outside Europe, it was a different story. SCEA and SCEI simply never picked up on the products with the same enthusiasm as their European counterparts, and seemed all too ready to dismiss them as a quirky British phenomenon when less impressive sales inevitably followed half-hearted promotion efforts.

It's only in the past week, with the end of his tenure at Sony on the horizon, that Harrison has revealed a glimpse at the frustration he felt with the rest of Sony over this issue. Speaking at a lunch event during GDC, he recounted being told by Japanese colleagues that there was simply no such thing as social gaming in Japan, and that people do not sit around on each other's sofas to play games.

Despite these rebuffs, Harrison continued to pursue the idea of social gaming - putting online-enabled versions of Singstar and Buzz for the PS3 into development, driving the vision for PlayStation Home, and evangelising the power of user-generated content in LittleBigPlanet. Meanwhile, of course, he also oversaw the creation of the firm's hardcore portfolio - headline titles like Killzone 2, MotorStorm and their ilk - but it's social gaming that is Harrison's real legacy to Sony.

And yet it is a bittersweet legacy. While Sony's consoles are still the product of choice for social games of some types - karaoke and quizzes, especially - the fact that Harrison's exhortations fell on deaf ears in Japan has seen Sony lose huge amounts of ground to its oldest rival in the games business, Nintendo. The Wii has destroyed any notion that people don't sit on one another's sofas to play games, or at least stand in front of them - but a little too late for Sony, who must now play catch-up to position the PS3 as a desirable platform for casual gamers.

Harrison's tenure at Sony has, at least, given it the tools to do exactly that. While Microsoft struggles to come up with a response to the Wii, Sony has healthy franchises that could - in time - make the PS3 into a welcome part of every social living room. It will happen, however, without Harrison himself.

His resignation, like Peter Moore's last year, leaves the game console business without one of its best-known and most respected figureheads - but we don't believe for a second that Harrison's ambitions for social and connected gaming have been fully realised, nor that he is simply abandoning them. Those in the industry who are concerned with reaching the mass-market and building the social credibility of gaming will watch carefully to see where Phil Harrison reappears.