Retrospective: Virtua Striker 3 ver. 2002

"Rainbow! Fantastic! Wonderful goal!"

These days when the previews for the latest iterations of FIFA and PES emerge, I find myself wincing a little. Not because the improvements I read about aren't worthwhile, because they frequently are. But every year offers something extra to learn: new tricks, flicks, adjusted physics, an overhauled defensive model.

That's as it should be, of course, yet as my free time is at a premium, I never really have the time to truly get to grips with either game to be properly competitive. I'll play the odd game with friends, sure, but I'm increasingly avoiding matches with online players who I know can out-feint, outmanoeuvre and invariably outscore me. Part of me yearns for something simpler.

The apparent death of the arcade football game, then, is something I find particularly frustrating. I wasted many an hour in my youth on the likes of Sensible Soccer and Kick-Off 2, and, years later, ISS on the PlayStation. But there was another football game I'd always play given the opportunity, and that was Virtua Striker. Every time I visited an arcade, that'd be the game I'd make a beeline for. I'd never stay long enough to get really good at it - I'm not sure I ever got past the fourth match on the Version '98 cab in our local Namco Station - but I found it every bit as irresistible as any of the newer, flashier machines.

So when the GameCube launched in 2002, Super Monkey Ball wasn't the only launch window title from Amusement Vision to make it into my collection. Virtua Striker 3 ver.2002 was the first opportunity I'd had to play one of my all-time arcade favourites in the comfort of my own home and I wasn't about to pass it up. Those bright, crisp Sega graphics didn't look quite as good on the smaller screen, but otherwise it was pretty much as I remembered it (although I never quite got over the scandalous omission of an Arcade mode, especially as one was present in the Dreamcast port of Virtua Striker 2 ver. 2000.1.)

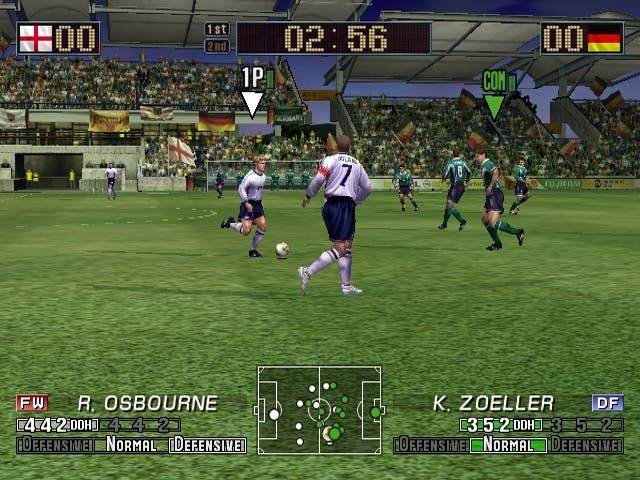

It certainly hadn't gained any extra complexities on its journey to console. Three buttons, no nonsense: short pass, long pass and shoot. The short pass button was used for sliding tackles, too (more on those shortly), but there was no sprint button, no finesse shot, no trick stick. It played nothing like real football - in Sega's vision of the beautiful game, possession changes hands every few seconds, and it's near-impossible to string more than four or five passes together - but once you were accustomed to such eccentricities, it became a surprisingly tactical game, albeit in a very different way from its peers.

Team strategy was more important than individual tactics. You could choose two formations at the start of a match (to be switched between using the Z button), while a squeeze of the right trigger allowed you to set your approach: attacking, balanced or defensive. While its play mechanics were simple, there was enough depth involved in finding the perfect strategy that Virtua Striker 4 introduced a feature whereby players could adjust team line-ups and tactics on their mobile phones.

That said, it was easy to understand why so many dismissed it. The automatic player switching was capricious, while the single camera perspective is so low and close to the action that you're often passing to players you can't see. The physics were odd, too. In certain positions, the ball would accelerate, rolling out of play or bouncing through to the goalkeeper at a faster pace than when it was struck. Defenders would regularly pull off bizarre scooped headers, somehow generating extra power and distance from a slow-moving ball to clear their lines.

Yet if the physics were unusual, they were also consistent. After a number of games you'd begin to anticipate when a ball was rolling too far, or when a tackle was about to come in. You'd learn when to slide in and when to hold back when defending, or the precise moment to release the ball before it was taken from you. In other words, it became predictable - and for once, that's not a criticism.

Indeed, in its literal sense, predictable isn't always a bad thing for a game to be. If something consistently behaves in a reliable manner, then it's something that can be truly mastered, a puzzle whose solution never changes. Virtua Striker may not have had the freeform feel of the real thing, but its predictability was precisely what made it a worthwhile alternative to Konami's more authentic simulations.

It helped, of course, that the presentation was so strong. The camera may not have offered the best tactical overview, but it made those wonderfully chunky player models stand out all the more. What's more, Sega expertly captured the pageantry of a big tournament, helped by what remains one of the liveliest crowds I've seen in a football game; roaring, jumping, swaying and waving flags, they offer more convincing support than the cardboard cut-outs of many footy games released since.

A neat touch in the game's career mode equivalent - Road to the International Cup - saw them spread more thinly during friendlies, but packed to the rafters for the finals. It helped create a sense of occasion that even FIFA could take a few pointers from. The visuals were certainly more attractive than the football, mind, a blend of wayward passes and vicious challenges that could make even the more cultured sides look like a team of Joey Bartons.

The frequency of slide tackles - accompanied by a sound akin to someone vigorously ripping up paper - turned games between lesser teams into attritional midfield battles; with no sprint button you were forced to play it about and really work for an opening. Even with a bit of practice it was difficult to thread more than a couple of consecutive passes together, and simply scoring was a tricky enough process unless you were playing as one of the very best teams.

That did, however, make each goal more satisfying, though your early strikes were never the prettiest. After a symphony of rips, you'd eventually win the battle of the sliding tackles with your forward on the edge of the box before jamming the stick against the upper-left or right of the analogue's octagonal gating (as close to the tactile pleasure of an eight-way stick as you'd get in that console generation) and watching as the ball fizzed into the top corner. The exquisite tension of that split-second before you released the button and your player's foot connected - more often than not hitting fresh air as the opponent made a last-ditch interception - made it a real explosion of joy when the net rippled, accompanied by the yell of the excitable announcer.

Amusement Vision made scoring in Virtua Striker a real event. You'd get a great replay of your strike soundtracked by the kind of bubbly, happy music that Sega doesn't seem to know quite how to make any more, and a range of celebrations from a thoroughly silly synchronised forward roll to your striker glugging a Sega-branded water bottle by the near post. And, crucially, you'd see a number in the top corner rating the quality of the strike. This was governed by a number of parameters: a shot from distance would generally earn more than a tap-in, while a scissor-kick volley was worth more than a header. But to get the biggest score, you'd need an uninterrupted build-up of passes.

Suddenly, the challenge changed. Scoring ugly was no longer an option. Instead, you'd attempt to score a team goal worthy of the Brazil side of the '70s, experimenting with formations and opponents to figure out where you could best work an opening and maximise the limited space afforded to you by the aggressive AI. Hearing the announcer delightedly herald "today's best goal!" was a moment of triumph even before the rainbow trail that followed the ball from its final assist to its resting place in the onion bag.

"Rainbow! Fantastic! Wonderful goal!" It may have been a slog to get there, but the reward was well worth it. I've sadly lost the memory card with the replay, but I vividly remember my best: a score of 649 as my Italy side carved apart Cote D'Ivoire before my number 10 swivelled to fire a crisp finish into the bottom corner.

Against a human player, it was never quite so simple. The predominance of tackles led to possession of the ball changing hands more often than a tennis rally unless you made a gentleman's agreement to refrain from sliding challenges. But why would you when fouling was such fun? Each card would bring about a comical animation, with the referee sternly flourishing cards at gesticulating players, furiously shaking their heads while standing on tiptoes as their victim rolled around, or hopped off clutching one knee.

After a while - I'm sure it's three red cards per side, possibly four - the ref won't book anyone else, which naturally led to a match between me and a friend where we competed to commit (and get away with) the worst possible foul. I lost, victim of a two-footed challenge launched from about five yards away that temporarily halted play while we dissolved into helpless laughter.

Despite AV's best efforts, a Virtua Striker career mode was never really going to work, and despite a few neat touches, Road to the International Cup proved something of a slog, throwing the game's shortcomings into sharper focus. There was, however, a brilliant unlockable in the form of a team comprising characters from the Sonic the Hedgehog universe. Watching Eggman fling himself to his right to palm away a fierce drive was quite something, while Sonic would arrogantly celebrate goals with his classic finger-wagging animation.

With console audiences moving onto the more sophisticated fare served up by Konami, Virtua Striker sold poorly, and though subsequent arcade instalments used the GameCube-based Triforce hardware, a home follow-up was not forthcoming. Virtua Striker 4 enjoyed some success in Japanese arcades for a time, but the updates dried up, and there hasn't been an entry since 2006.

Given Sega's recent fortunes, it's even more unlikely to ever see a revival, which is a shame for a game that in different circumstances might have been able to find a home on digital platforms. With PES and FIFA jostling for the affection of the serious football fan, there's surely a gap in the market for a decent arcade football game. If only Amusement Vision were given the opportunity to fill it with red cards, rainbows and wonderful goals.