Rez Infinite: VR's first and best?

Mizuguchi's masterpiece assumes its final, perfect form.

Tetsuya Mizuguchi sits in a swivel chair under a lamp in the middle of a dark, empty room inside an office complex by Aoyama Park in Tokyo. A totem of projectors beams footage from the director's masterwork, Rez, on three of the four walls around him while a polished Sony VR headset warms his feet. Miz, as his friends know the director, has always shown a talent for theatrics. Years earlier, while promoting Child of Eden, another game that splices music, light, and play using emerging technology, he stood before an audience at BAFTA's headquarters in London and conducted the Kinect camera like he was playing the Royal Philharmonic. A day before we meet, he appeared on stage at the sweltering Tokyo Game Show dressed in a jet-black onesie, performing the game that has, in recent months, brought him out of his retreat into academia. Squint and it could have been a member of Daft Punk grinning beneath the helmet.

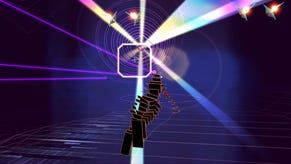

"This is the version of the game that I originally conceived" is the go-to phrase of the film or game director on the PR trail for a remaster (or, in the case of George Lucas, a tic he'd repeat to the beleaguered Star Wars CG staff before he'd finished his breakfast pancake). In Mizuguchi's case, the words have a different, weighty resonance. Sure, Rez Infinite is, when viewed from one angle, little more than a repeat of the same game, re-forged in 4K-resolution (the game can be played, it must be noted, on a television screen; VR is optional). But view the game through the PSVR headset, particularly the new, expansive, freeform Area X, and it's nothing short of revolutionary, the kind of mind-wrecking euphoric dive through another dimension that video games, even in their earliest forms, always promised.

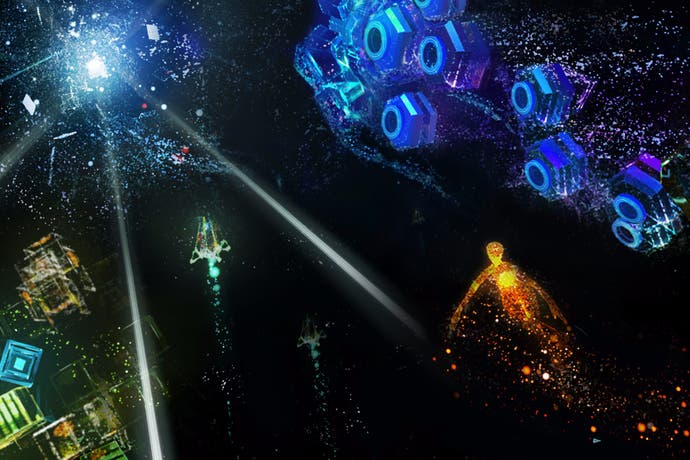

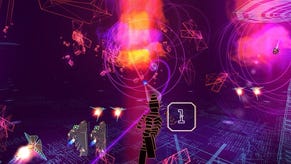

Area X's trick is to free you from Rez's invisible rails which, in the original game, guided your character through its glitchy firework displays as if you were riding a rollercoaster to the centre of the earth. Now you're able to fly through space in whichever direction you choose to look, wheeling in great loop-de-loops through the stars, while firing off fistfuls of neon-tracing homing lasers to light up the murk and keep your path free of foes. What should be disorientating feels effortlessly navigable. What should be nauseating feels clear-headed and sturdy. "Pretty much from the very beginning, when Rez was floating around my head as an idea, its world already existed in a virtual reality-like form," Mizuguchi admits. In 2001, however, VR was an old joke, a futuristic tech that, like Concorde, had been consigned to history. Miz and his team had to settle for flat-screens and rails. "There was a lot of frustration for me," he says. "Maybe even stress in having to squeeze the world into that format. So I made myself a promise: when the time came, this would be the game I'd recreate in virtual reality. I owe it to Rez to make a complete version of that game."

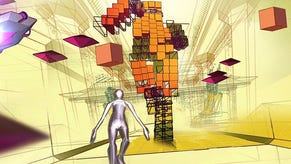

Rez Infinite is a re-visitation, then, but also, in Area X, a re-imagination. "We started from the idea: if we were making the game from scratch today, if we were given that second chance, what would it look like?" For Mizuguchi, its not been a task he's had to face alone. There are old comrades among the twelve team members including Osamu Kodera, one of the programmers on the original, Dreamcast version of Rez (Kodera was also lead programmer on Lumines and Child of Eden). Mizuguchi says that he feels an unusual creative affinity with Kodera, particularly when it comes to recreating the effects of synaesthesia on screen, the mental condition whereby some humans are able to see sound as colour, or other sensual blends. "He and I talked at length over the years about synaesthesia, and how we try to put that into our games," says Mizuguchi. "We have very few words we need to exchange. He can interpret what I say with ease. He's my soul mate in game development."

This affinity, together with that the pair enjoy with art director, Takashi Ishihara (who first played Rez while he was in still high school and was so affected that he applied for a job to work at Sega alongside Mizuguchi) is abundantly evident on screen. Area X, a galactic joyride that lasts for around 30 minutes, before a concluding battle against a giant and handsome spectral woman, melds seamlessly with the rest of the game, as if it was a hidden room that had always been there, now joyfully unlocked. The new soundtrack manages to mesh with that the of the 15 year old original (itself somehow immune to dating) too -although Mizuguchi says that he feels the new material is more "organic" and "emotional" than the frostily robotic pips and snares of the original.

At the Tokyo Game Show, Rez Infinite, which appeared on Sony's booth as part of its PSVR launch line-up, stood almost alone in the halls which were otherwise largely filled with lascivious virtual reality demos, grubby shooters and hyperactive RPGs. It's a game that seems to come from a different tradition, one that traces its lineage back to Kandinsky, not Rambo. "I agree with you in that, when you just walk around TGS for a day, it feels like we lack some diversity in the games being offered at the moment," says Mizuguchi, softly. "Independent developers are bringing in other kinds of voices, but they don't currently receive the kind of they need to stand out, or to be supported in a way they can fuel more creative ideas. Maybe that's just the reality we're looking at right now."

Regardless, for Mizuguchi, returning to Rez has had an invigorating effect in terms of his artistic energy. "A lot of folks probably thought I retired from games when I joined Keio University," he says. "It wasn't exactly that. I just needed to recharge my batteries after Child of Eden. Changing your environment and surroundings and adding other things to your own experiences is crucial when it comes to inspiration." Even while teaching media design (which Mizuguchi still does) he continued to work as a designer. "I was working on Area X in my head, on and off for about two years," he says. "Figuring out how it would all work, how I wanted it to feel and so on. So when the time finally came to go into production, it was all fairly quick. I've been waiting for this moment. In the 25 years I've been making games this is the most exciting time for me. And now I have new ideas that, who knows, will maybe fuel me for the next five or ten years."