Rise of the Argonauts

Fleeced.

Away from battle, the story becomes rather more endearing as you deal with the problems facing the people you encounter, each of whom is suffering at the hands of some local evil you need to uncover, and here the game is relatively successful at marrying its ancient inspiration to basic detective work. On the apparently cursed island of Kythra, for example, you find yourself seeking evidence to save the life of a condemned criminal, before exercising your judgement to decide the fate of his rather more tainted companion, and as you consider the failings of Medusa and Perseus you find yourself caught up in an absorbing, interactive debate with Phaedon over the right of the Golden Fleece to exist at all.

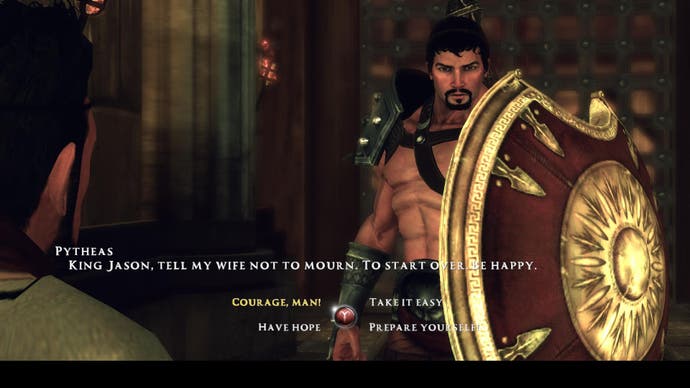

But these relative successes are marred. Phaedon's philosophical jousting, for example, is the other side of a crude memory game, and followed by a dull boss fight, while decisions about how to treat the people you encounter are often trivial. You simply pick the response that serves whichever god you're currently trying to get some powers out of, aware by this stage that the structure of the game is rather more linear than it lets on. Choice is generally an illusion, if it's even offered, as it isn't when you're invited to either bludgeon your wife's murderer to death, watching on from his perspective after ten minutes of playing, or stand there motionless and not play the game any longer.

Argonauts' illusion of scope is initially more successful, as Unreal Engine 3 is used to conjure a vast game-world, but this is also shattered, and quickly, by narrow corridors of movement, barricaded arbitrarily, and the lifelessness of the places you visit. Iolcus, Kythra and Saria are galleries of motionless non-player characters, only some of whom have things to say, and even the more invigorated Mycenae is stunted by its own immobile NPCs and the obligatory minutes of jogging around it to reach points marked on your map.

In the absence of an on-screen guide, it's necessary to dive into the pause menu's map screen wherever you go, and regularly, to find the NPCs and locations of relevance marked along its prescribed pathways. Like the combat and conversation systems, it leaves you in no doubt where you need to go, and in no doubt of the superficiality of your orienteering between people and places designed to shunt the game into its next phase, despite the fact you often have more than one thing to achieve at a time.

For all this, Argonauts' premise might have been its redemption. Combat, exploration and conversation may be processional, but there's something intriguing about Jason's apparently unwitting selfishness, upon which the game builds its masks of virtues inspired by its principle gods. Were the game to realise this, it might make up for all the hours spent wading through long-winded, often incidental conversations, grimacing at the pauses between speech (even in spite of the ability to preload your chosen responses) and the vacant expressions of the stony-faced cast.

Given what a large number of Greek myths were meant to symbolise, Argonauts' cultural inspiration cries out for a measure of narrative justice. Surely Jason must pay for the decision he has made - to save himself from the certainty of grief and solitude - however noble the acts it has driven him to perform in service to that quest?

But if this is a cautionary tale, it's one of this player's misplaced, increasingly desperate hope to derive some greater meaning. There is only one path, and while you meet a few interesting people and solve a few worthy problems on the way, the fundamental paradox at the heart of Rise of the Argonauts is never explored or resolved. Instead, the game concludes disagreeably, as virtually everyone Jason is supposed to protect is left tortured and dead by his original departure, and he simply has a party because he got what he wanted. For an action RPG elevated beyond its serviceable components by the allure of rich mythology to end in such a desperate contradiction is comprehensively self-destructive.