Retrospective: Robotron: 2084

The soul of a new machine.

How much trouble? Experimentation began, and it turned out that the whole thing was largely a numbers game. How many sprites could the chip handle on screen at any one time? What was the point at which it became fun? What was the point at which fun turned to bedlam? Hey, and where did it balance out? Where did slowdown kick in, and where did the AI suffer? And did any of that even matter?

Most games would give you a handful of enemies at any one time and that would be enough. Space Invaders amped things up a bit, granted, but most of those advancing crab monsters were actually just lumpen targets to whittle away at - bland nightmare machines who were born only to die at a distance. For the game that was becoming Robotron, a mere handful of enemies was actually pretty boring. You needed dozens and dozens of the little mofos, flocking towards you, racing in from all sides, and then, suddenly, you were under its spell.

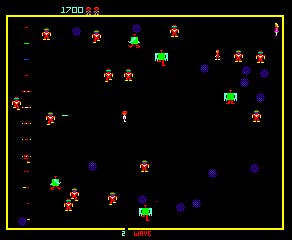

The game was most fun at the point when it was actually becoming slightly terrifying - it worked best as a deranged and entirely one-sided kind of warfare, with the player zapping into the middle of the screen to find himself totally surrounded by hordes of brightly-drawn killers. It's 2084: the robots have taken over, you've been deemed "inefficient", and they've got you cornered.

That was part of the magic - that energising claustrophobia, heightened by the simple colours and stark borders that hemmed in an otherwise completely empty screen. The other part was variation: the robots who were coming to get you were all coming to get you in their own way.

GRUNTs, the stylish little red ones with the bright green visors, were just caught up in a headlong dash to connect with your frail human body. They chugged after you wherever you moved and died by the half-dozen.

Hulks, meanwhile, pretty much ignored you, but couldn't be killed, only knocked gently off course by your shots. Spheroids buzzed around the screen in nasty, sweeping diagonals, inevitably winding up in the corners, and if you didn't get to them in time they would spawn Enforcers, who Hoovered around the place unpredictably and showered you with spiky little bullets. Brains could fire guided disco missiles at you and turn innocent humans into zombified Progs, while Quarks may have looked like the kind of harmless visions you get if you stand up too quickly after a long bath, but they spat out Tanks.

Tanks were probably the worst thing in the world that could ever happen to you, trundling back and forth in blocky clusters, and letting loose with squash balls that would bounce off walls, punching through your lives in no time at all. Finally, there were always Electrodes to take into account, too: the deadly little bits of furniture that Jarvis and DeMar pinched from another game and then scattered randomly across every room.

And all those pieces, obeying their own little rules, created something that was pretty fascinating - just as long as you weren't playing it, in which case it was a lot more emotional than that. Strange behaviours emerged, things that hadn't really been coded into the game, like the fact that Quarks would fling Tanks together in little nodes of death, or that Enforcers got themselves stuck on the edges of the screen, so their arcing shots would criss-cross the play area at 45-degree angles.

The addition of wandering family members - the last human family on Earth after the Robotrons took over - only added to the brilliant parade, giving you something to collect for points (which translated, naturally, into extra lives) and making you play in a murderously schizophrenic manner. Even when you knew you shouldn't, you would find yourself lured to your death again and again by Mommy, Daddy and little Mikey. They were like digital sirens, tempting you towards trouble.