Saturday Soapbox: Guilt By Association

Putting the "You" into "You Bastard".

Games never have much difficulty making us feel like a hero. Cheerful psychopaths are the bread and butter of entire genres. Guilt? That's trickier. It's a rare game that even tries, and only a tiny fraction of those even come close to making it good to feel bad.

Spec Ops: The Line is one of them, and while I am about to be critical of one of its big scenes, make no mistake: it's a seriously impressive piece of narrative, blisteringly dark, and phenomenal in both storytelling and character development. I could enthuse about much of it, and almost certainly will at some point - when the big scenes no longer reside in Spoilerville and more than six people have actually bought a copy.

At heart though, it's the story of one man, Walker, with the best of intentions and the worst of luck. If Walker bought a starving man a chicken sandwich, that sandwich would turn out to be roast salmonella with mayonnaise. If he helped an old lady across the road, he'd suddenly realise he was in 1888 and just saved Hitler's mum. Walker, essentially, is you: buying into this adventure to be a hero, only to find tragedy waiting.

One scene though stands out for me as a great example of how even with superb narrative staging and a spectacularly brutal outcome, guilt is one of the hardest won of all player emotions. It's fairly near the start. Walker and his squad, Adams and Lugo, are facing a massively fortified installation called The Gate, which conveniently offers a nice secluded perch with a mortar full of white phosphate - presumably dropped by the same magic equipment elves who head into the deepest depths of long-sealed tombs to make sure Lara Croft is never far from a shotgun when a T-Rex shows up for dinner.

At first glance, this looks like a moral decision, but it's not. At least, unless you count switching off the game and throwing away your money on principle. Despite Lugo insisting there's always a choice, Walker is very clear: no, there isn't. You're meant to either agree and fire the mortar, or rush up to the cool new toy to gleefully set lots of enemy scum on fire. Whichever you choose, you get your wish, but more than you bargained for - a forced march through the burned, tortured flesh of what have to be considered your victims. It's a pivotal moment for the story and for Walker, not least in terms of how his initial declaration of there not being a choice affects him in future encounters.

And if you play it like that, the scene works brilliantly.

The catch is that while Walker is a representation of us, we're not actually Walker - and behind our impenetrable shield of screens and quick-loads, the calculations are different. Take a moment to breathe before hitting the mortar and you realise that while Walker is correct, there is no choice. That's because you're unable to leave the overlook rather than the weight of opposition - the exit only appears post-decision. It's fine for a game to ultimately force a decision or horrible moment, and the results can be ghastly. To instill guilt, though, the player has to be invested in the act. Here, I felt as personally guilty as I did that time I blew up the planet Alderaan by renting a copy of Star Wars.

Again, I reiterate, I have a great deal of respect for Spec Ops' narrative, and this is by no means a badly done scene. It's simply a bit of an emotional disconnect that needed one key change to play out properly for jerks like me who won't follow the script: the chance to try and fail. You can sort-of do that and get into a firefight you can't win, but what makes it artificial is too blatant. It's like a magician holding out the Ace of Clubs and saying "Pick any card." Even if he was going to force that on you anyway, it needs more.

What was needed was to be able to say "No, I'm not going to use the mortar!" only to have to be slapped down by snipers, goons or whatever else until you have to agree with Walker's original sentiment and pull that trigger together. It'd be out of context in the sense that Walker would never have that luxury in the real world, but in most cases it's more jarring to worry about a game's unreality than simply roll with it. After all, by this point we already accept he can shrug off rocket launcher blasts to the face...

What Spec Ops absolutely nails though is the core reason why most games that do make us feel guilty manage to achieve it - not simply pointing at something horrible and saying "You did that!", but by finding ways to subvert our desire to do the right thing. Sure, there are exceptions to this, like the Little Sisters in BioShock (ignoring the silly Bad Ending), Morte's encounter with the Pillar of Skulls in Planescape Torment, and the big twist point in Oblivion's amazing Dark Brotherhood quest line. Most of them, though, revolve more around finding the point where being evil stops being fun and stopping you from continuing down it, rather than making you specifically regret past decisions.

Examples that have worked especially well for me include my original failed attempt to reunite the geth and quarians in Mass Effect 3 (leading to Tali's death and my one exception to my 'what happens stays happened' rule, because the quarians are my favourite Mass Effect race), inadvertently helping Roy massacre Tenpenny's less evil houseguests in Fallout 3, and Eleanor's transition from noble friend to psychopathic menace to society in the sorely underrated BioShock 2 - at least on my second, 'evil' playthrough.

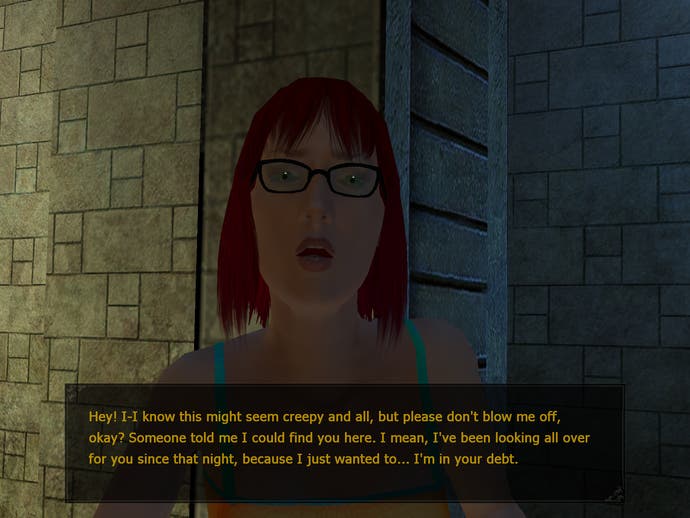

The one that really sticks in my mind though is Heather Poe from Vampire: The Masquerade: Too Many Colons: Bloodlines, which nails the cynical 'no good deed goes unpunished' mood of that game, and mixes it with a little human frailty for good measure.

In a nutshell, the deal is you find a dying girl in a hospital, save her life with your magic vampire blood and then go about your business. That seems the end of it. A few missions later though, she catches up with you in another part of town, having been transformed into a ghoul - addicted to your blood and devoted to you.

Like other examples, this is a 'how evil are you willing to be' test at heart. Even if you start by treating her as an amusing toy, from having her dress up in different outfits to seeing what benefit a personal slave can offer, things quickly get darker. She gives you her college funds, since she won't need them any more. She even finds you a fresh victim, locking a guy she picked up in the bathroom for her not-so doting master's lunch.

If you're a nasty vampire, no matter. You even get some nice armour out of her. If you have more of a soul than your character though, the fact that you've saved her life only to ruin it soon takes any 'fun' out of this, at which point the second stage kicks in. If you're nice enough to want to free her, you then find that cutting the cord is brutal - or at least was, when Bloodlines' facial animation was cutting edge.

You have to be cruel to be kind, repeatedly delivering verbal face-punches to make her take the hint through a dialogue tree that lets you chicken out at any point. And just to add one last little kick, even if you do all this, it's clear that she has pretty much no chance back in reality. Hero!

Being a dark kind of game, it's also notable that Bloodlines itself makes no real comment on this - and I'd argue that most of the successful games don't. Situations worthy of guilt absolutely should have repercussions in the game world, but there's a difference between characters responding and some mechanic like karma showing up to make it absolutely clear that the designers who wrote that bit are Very Disappointed In You.

That's important, because in games as in life, it doesn't take much to let us off the hook, or shift blame. The original BioShock's failure to understand that you were totally thinking of the needs of the many for instance, or its failure to offer a road to redemption trumping our moral lapse of having killed lots of innocent little girls for personal gain. In Spec Ops: The Line, it's having to take a character's word that there was no choice but to commit an atrocity. Sometimes, the attempt itself is simply so ham-fisted that the power is lost. Playing Modern Warfare 2's No Russian level for instance, I took great pleasure in being the best terrorist ever, just to spite the game's attempts to make me feel bad. Hold up, Makarov! There's a granny behind that bin!

When it does work though, guilt is a powerful emotion - both for its raw player punch value, and for its scarcity. Nothing binds us to a character more than the shared desire to make sure everything turns out okay, or offers investment in their story like wanting to atone for a bad decision. It doesn't have to be something that makes you question your worth as a human being; it could come from a carefully scripted situation or something emergent, and in many cases, it doesn't even have to be deliberate. I stopped playing Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, for instance, because a couple of missions crossed the line between 'fun crime' and 'goddamn, I should be arrested.'

Moreover, when a game provides that sense of guilt and regret, it's one of the very few ways it can affect us in ways no quick save can magically fix. Heroism fades, in games as in reality. Guilt hangs around. Sure, you can hit restart, but you'll always remember what you did and what happened next. May the pixelated gods have mercy on us all.