Saturday Soapbox: It just worked?

Five years out, what has the iPhone done for gaming?

The Murderer is a Ray Bradbury short story from the 1950s, and it tells the tale of a psychiatrist interviewing a man who's been on a very peculiar crime spree. In a ten-minutes-into-the-future sort of world in which personal communication devices are pretty much omnipresent, he's gotten himself arrested for killing his telephone, his wrist radio communicator, his inter-office chat machine, his television, and his hideous, babbling, overly-connected house. After conducting a quick appraisal, the psychiatrist goes back to his desk to write his report, and the rest of his day plays out as an endless series of interruptions: this phone and then that phone, the wrist radio, the intercom, the phones again.

I first read The Murderer about ten years ago, and it seemed powerfully prescient: texts arrived and calls came in as I ploughed through it - my phone never seemed to stop buzzing, in fact. I read it again last week, however, and it had lost a little of its sting. The era of Facebook and Twitter should have made it yet more timely, if anything, but I just didn't feel Bradbury's soothsaying coming through quite as strongly in 2012. Social media has certainly done its bit to give us all the feeling that we now live, rather awkwardly, in our friends' mouths, but if I still spend my day pinging between phone calls, emails, texts, and, um, FaceTime, I don't notice it as much. That's because the relationship I have with my phone - and isn't that a weird proposition? - has really changed of late.

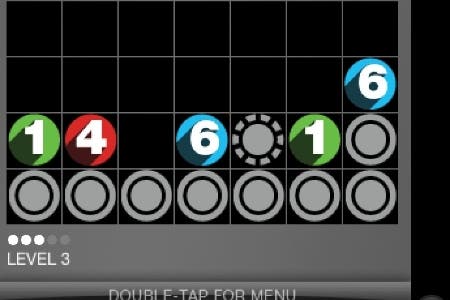

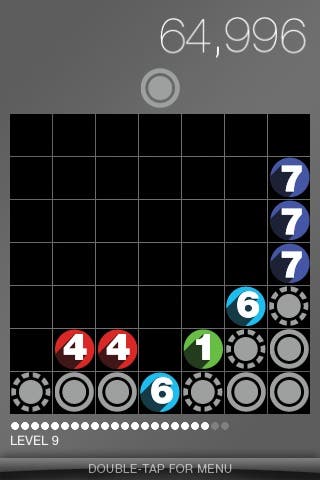

If I was the psychiatrist in Bradbury's story, then, the end of the narrative might go like this. Back to the desk for a few minutes typing. Check Letterpress and make a couple of plays. Spend a quarter of an hour with Drop7. Back to typing. Back to Letterpress. Over to Solipskier. Over to Hero Academy. Tiny Wings, God of Blades, Taiso. Aaaaaaaaand fired.

This month marks the five-year anniversary of the iPhone's arrival in the UK, and it's a good time to take stock. I don't know about you, but my gaming life has changed significantly. I'm not about to step away from the console under the telly or the PC in that weird new-build nook beneath the stairs, but I am finding games threaded into my life in places where they previously weren't. Theoretically, I could have been taking my DS or PSP on the train or the bus for a good part of the last decade, but I rarely have, and I've rarely seen that many other people doing it either.

These days, however, I see iPhones - and Androids and Blackberries and all that jazz - out on display on public transport all the time, their screens bright with falling blocks, platform hoppers, and the creeps and turrets of Tower Defence. The people messing around with them aren't the usual suspects, either - they're characters of all ages, and when they're not playing as they rattle between stops, they play when they're queuing at the checkout, bored at the cinema - these guys are the worst, incidentally - or even wobbling down the road and narrowly avoiding open manholes as they squeeze out a few last seconds of Fieldrunners or MovieCat. Somewhere along the line, mobile games got in - right in - and got beneath our skin. Somewhere along the line, games won.

I realise that finding any of this in any way surprising has become a bit of a cliché - Oh, it's a pensioner playing Angry Birds! Ah, it's my mum, calling me up about that Simpsons tappy-tappy thing. I recently had a scan over a magazine article I wrote at the very start of iOS gaming, though, and realised that these truisms weren't immediately, well, true. The piece I wrote hails from the tail end of 2008, and was written at a time when there were just 1200 gaming apps on iTunes. A disinterested reader might find the text, with its suspicions about the long-term prospects of the App Store, mildly comical today. As the writer, I find it a lot more embarrassing than that.

This article starts by talking about how underwhelming the early iOS games were - to a certain extent, I still don't think they were a truly vintage bunch, actually, and I even managed to rope in some industry figures to back up my scepticism. Things get really interesting, though, when I start to gather together the various problems the fledgling platform was facing. There are no real gatekeepers for the store, suggesting that quality might suffer in the long run. The prices started low and quickly went lower, too, meaning that it could theoretically become hard to incentivise developers into putting too much time or money into games - or that they could resort to bizarre tricks to stand out from the masses or claw back revenue. Primarily, though, the iPhone just looked like a very confusing gaming device. After all, it wasn't designed as one.

Tackling these problems backwards - it seems fitting with the benefit of hindsight - that last issue actually seems like something of a godsend today. While the early days of apps passed in a cludge of naff tilt-based kart racer ports and virtual joysticks, the best designers quickly decided to approach the touchscreen more imaginatively, and they've ended up doing some astonishing things. There are dozens of novel, satisfying ways to control everything from a top-down dungeon crawler to a fast-paced platformer on iOS now, and neat new ideas are popping up all the time, too.

As creators battled the lack of buttons, games speedily became more focused, often automating unimportant elements such as forward momentum in autorunners - a newish genre that owes an awful lot of its success to smartphones - and zeroing in on the interactions that really mattered, like jumping or sliding. Everywhere you look, in fact, so much feels fresh and surprising. Driving games like Smash Cops allow you to steer cars around by prodding them, sports games like Flick Kick Football let you score goals with a well-timed swipe. Indie designers such as Michael Brough have turned Apple's touchscreen into an abstract battlefield with games like O., while bizarre genres like slicers, shakers, and trace-'em-ups have become increasingly mainstream, and you can even find absolute oddities like interactive audio dramas if you look hard enough. Sure, it's probably the rare thirty-something gamer who won't wish for a few triggers and the odd thumbstick on occasion, but there are games being made with no need for sticks or triggers or buttons that would likely never have emerged otherwise.

And if developers have taken inspiration from the fact that the iPhone wasn't designed with games in mind, their games still benefit from the things Apple's device actually was built for: connectivity and the asynchronous apps it's lead to have helped resurrect the leaderboard era of arcade, for example, while the fact that you have your iPhone with you all the time, that you don't need to worry about turning it on, booting it up, or fumbling around for cartridges before getting started, allows games to be part of your life wherever you are. Most crucially, perhaps, the ease of downloading all these low-priced or freemium apps - if not necessarily the ease of finding them - means that you're likely to try out more games than ever, and dabble in genres that you're unfamiliar with. I sometimes imagine telling my eleven-year-old self that in the future I'd be able to take a punt with a new videogame on a whim. (Sadly, my eleven-year-old self is busy reading Mad magazine and digging holes in the neighbour's garden, and he doesn't seem to care.)

Oh yes: finding games. The fact that gatekeepers aren't as intrusive in the world of the smartphone as they are on a lot of other platforms has continued to shape the mobile gaming landscape. The results are more mixed here, most likely: it can be hard for the good games to get their moments in the limelight, and the torrents of titles released every day have given nasty cloners, who will tackle everything from mainstream hits like Tetris and Super Mario, to plucky indies such as Radical Fishing and Johann Sebastian Joust, just the platform they need to work their grim magic.

That said, the bad stuff is balanced out by the democratisation of design: sometimes these days it seems like anyone can make a game, and if often feels like anyone has, too. This - in unison with that weird selection of inputs - has seen smartphones drastically expanding the genepool of games in terms of everything from genre, art styles, subject matters and business models. There's more trash to wade through to find Drop7, perhaps, but a lot of the trash is fairly interesting. Coupled with middleware like Unity and the increasingly omnipresent Box2D, smartphone gaming has become a vital component of the burgeoning indie scene, and you reap the rewards of this outpouring of wayward creativity every time you're stuck in an airport lounge or waiting in the queue at Homebase. And as with all digital platforms, bad games can even become good games over time, as designers pick through the metrics and release updates.

So I love smartphone gaming, and I love what Apple's helped create, but even now I wouldn't want these things to be the only games I could play. There's still something lastingly great about a lavish console title, while PC is probably the most wonderful games platform the world has ever seen right here and now. It's living through a golden age whether you're after the high-end stuff, the free-to-play world-shakers, or the bizarre and baroque expanses of the indies. iOS - and Android, and the whole smartphone movement - has unquestionably changed gaming in lasting ways, though: broadening it, opening it out to new players, giving it a bit of a spring clean. For designers, there are new problems to go along with the new opportunities, perhaps, whether it's the dynamic marketplace of iOS and Android, with its changing tastes, financial plans and terms and conditions, the endless fight against plagiarism, the big publishers rushing in, or the eternal difficulty of standing out from the crowd. For players, though, it means more games and different games: who could complain about that?

The final irony is that Apple's revolution doesn't seem to have been particularly intentional. I was talking to an American designer about the iPhone recently, and he went off on an entertaining five minute rant about how Apple has always hated games and in fact spent a fortune in advertising trying to make iOS primarily about productivity. Games beat productivity, though, and games rushed on to fill new screens and embrace new control schemes, too, gathering up new business models and new players along the way.

Games won.