Saturday Soapbox: Loving the science, but don't forget the art

The rise of data-driven development has all sorts of benefits, but it shouldn't run the show.

We've all got lost in games. I don't mean that we've become so engrossed that external factors cease to matter - toast burns, cats starve, love falters, etc - although if you're reading this site then that's probably true as well. I mean we've gotten lost in games. It used to be a common complaint, in fact, that games spun you around or suddenly stopped saying new things and it would take ages to figure out what you were expected to do.

It used to be a common complaint, but these days not so much. These days it's actually pretty rare, and there's a reason for that: over the past decade, game developers have moved beyond simple bug-testing and started tuning their games in response to the way people actually play them as well. One of the most famous examples of this was Halo 3, for which Microsoft (then owner of Bungie) put the game through exhaustive testing, chronicled by Clive Thompson for Wired, which would reveal, for example, that a lot of players didn't spot some grenades on the floor just before a big skirmish and died as a result. Knowing why people were getting frustrated in situations like that helped Bungie make the game stronger. Just saying that it was the player's fault wasn't good enough any longer.

Just up the road, Valve has gone famously nuts for this stuff. I talked to Chet Faliszek about it a little back in 2009 just before Left 4 Dead 2 came out. "We actually have a psychologist that works with us, and we have outside playtesters come in a few times a week," he explained. "They get recorded playing. The level designers watch what happens when people get lost, and we talk about what's going on. You can normally see. It'll be that they're all excited about this little red thing they see, and it's just a kerb painted red, but they run over there. You see this happen enough times, and you realise you need to lead their eye the other way. You can say the player's wrong the first couple of times, but you get real clarity when the tenth person's still going to that little red thing and excited about it."

(I seem to remember Valve became obsessed with solving this problem after they had to stick a guy with a gun up on a platform way above you in Half-Life 2: Episode 1. Why? Because if you didn't have to aim up there at precisely that time then you wouldn't be facing the right way when one of those giant Combine ship things flew overhead. For a studio that sometimes sounds more like it's trying to save the world than develop video games, that one must have grated.)

In both of those examples, you'll note that the studios would film the people testing their games. They do this partly so they can refer back to the videos and see exactly the process each player went through, but they also do it because they know that player testimony alone won't be reliable. People aren't great at analysing their own behaviour, especially when they're distracted, and often claim to hold opinions completely opposite to the ones they act out. I'm bored of using the example of the "Boycott Modern Warfare 2" Steam group showing everyone playing Modern Warfare 2 the day it came out, so how about something from the world of toilet paper? Consumers always say they're immune to TV advertising, but how many people - how many of you - subconsciously reach for Andrex because of the puppy on the TV?

This is a tough one for developers, too, because people may not always know what they want, but that won't stop them being extremely vocal if they think they know what they don't want. "It's a very delicate balance," is the way Victory Games' Tim Morten put it when he spoke to Eurogamer's Christian Donlan the other day. "On some past Command & Conquers, we've had a very vociferous audience, and the changes we've made to those that shouted the loudest were not necessarily the best for the game in general. This time we'll have the benefit of all this back-end data which we're hoping will really let us steer it in the right direction."

There's an inherent danger with this, though, for which I'll refer back to Wired's Halo 3 article. Thompson writes: "After each session [Randy] Pagulayan analyses the data for patterns that he can report to Bungie. For example, he produces snapshots of where players are located in the game at various points in time - five minutes in, one hour in, eight hours in - to show how they are advancing. If they're going too fast, the game might be too easy; too slow, and it might be too hard. He can also generate a map showing where people are dying, to identify any topographical features that might be making a battle onerous."

See, I love the fact that I don't get lost in games any more, or at least not so much (I'm still pretty stupid), but I'm also a little worried that all this data might be shaving down the artistic edges in a few places. Take the above example. What if those topographical features that are making a battle onerous are supposed to be making it onerous? What if it's a section where Master Chief is completely outgunned and you're supposed to feel like you only just survived? What if dying a couple of times is meant to give you a sense of your own limitations?

Maybe Halo's a bad example. So what about, I dunno, Uncharted 2? The Uncharted series has issues with player agency, for sure, but it's nothing if not brave about what it gets you to do within its sometimes-crude limitations. Uncharted 2 has a whole section, deep into the game, where it pretty much just stops for half an hour. You can't run, you can't shoot - you can't even speak to anyone because nobody speaks English.

When I think of Uncharted 2, that's the section I remember most vividly. I enjoyed the train level as much as everyone else, and it's a wonderful game in many other ways, too, but that moment of friction - waking up with my adventure stalled by circumstances beyond my control, meeting new people and having to rebuild that lost momentum - is the part I loved. Putting it in there was about managing tempo, for sure - and, hey, I'm sure the data says that's good for players too - but it's also a brilliant touch of authorial intent that reminds you: someone made this.

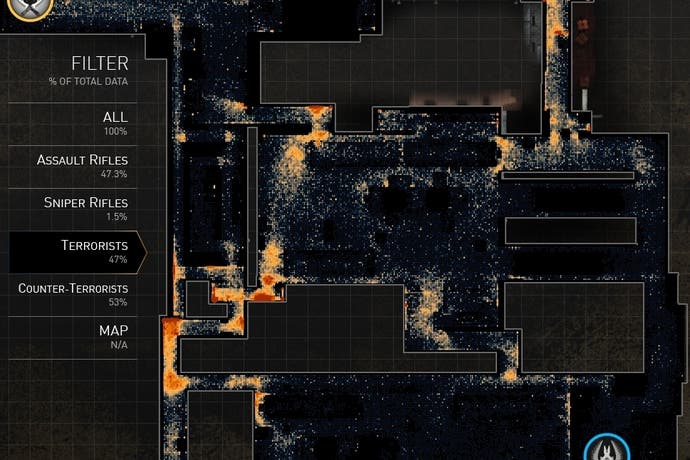

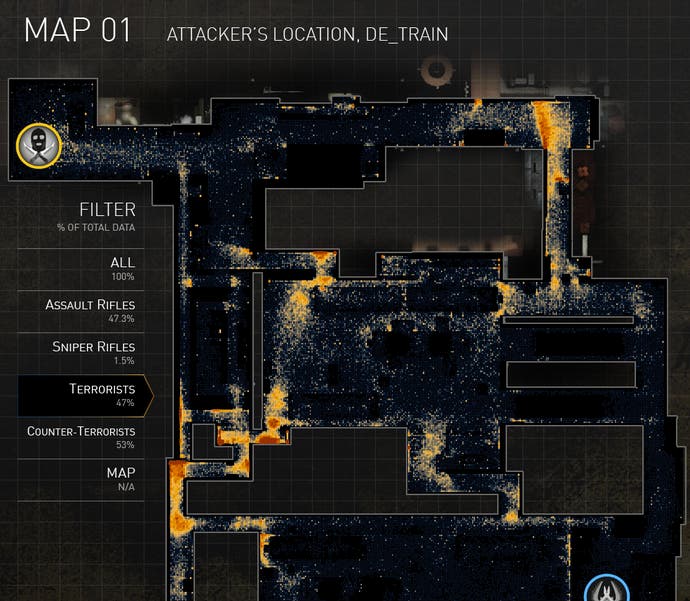

If you're looking for the opposite, I read a press release recently from Splash Damage about its new game Dirty Bomb, which talked up the 'Echo' technology at work behind the scenes. "The project is led by Dave Johnston, creator of the world's most popular Counter-Strike map de_dust," Splash Damage splashed. "Dave knew that no level designer can be present every time their map is played, so he created proprietary technology that uses cloud-based services to collect every event in every game session, worldwide. Echo then visualises this data for developers, letting them improve Dirty Bomb's compatibility, balance, maps, character classes, skills, weapons, frame-rate, network latency, and - most importantly - team play."

The reverence is understandable - nobody likes a bad multiplayer map - but I hope it's not always used in preference to the designer's instincts. After all, de_dust, Johnston's most famous creation, was famously lopsided: the Terrorist team was more likely to be wiped out by racing through the tunnel side of the map and up the ramp, leading Valve (yeah, those guys again) to eventually rebalance it by introducing a stairway over there so the Terrorists could abort a charge if they sensed defeat. I like both incarnations, but I prefer the original precisely because it was lopsided: it meant that victories earned by taking that route felt sweeter.

Meanwhile, the world heavyweight champion of authored experiences, of course, is Hideo Kojima. There are doubtless times during development when Metal Gear Solid is adjusted to make it a more even experience for the player - trimming enemies in this section, tweaking a level layout in that one - but, whether you love or hate his work, Metal Gear Solid doesn't give you the feeling that Kojima has a building full of play-testers hooked up to biometric systems analysing whether or not they want to hear his meditations on what it means to be a soldier. And if he is getting that feedback, you get the impression he is nodding politely and then going back to tweeting pictures of his dinner. That's a nice balance, and as we see more and more developers talking about their analytics and metrics, I hope it's one they also seek to preserve.

If we do, then maybe we'll see more games like Dishonored, and I'm sure we'd all like that. Dishonored was a slick, polished production in every respect - I am still in awe of the PC version's quick-load times - but it had a clear creative vision and when it came into contact with devious or confused players during production then it drew inspiration from them rather than blunting their instincts. Some developers, faced with players teleporting their way beyond the boundaries of their expected behaviour, would have stopped them horsing around. Arkane went the other way and made it a central feature.

Data's great, see, as long as there's a bit of art to how it's applied.