Saturday Soapbox: Whatever Happened to the Working Class Hero?

How gaming's obsession with empowering fantasy is making us lose the human touch.

There's been something missing from the gaming landscape. Something that's been bugging me, though I haven't been able to put my finger on it. It was Spelunky, bizarrely, that knocked loose the mental blocks and made me realise what I was pining for. Though that game's nameless hero owes most of his DNA to rock-hard NES classic Spelunker, there's also a dash of Manic Miner in there. And that, I realised, is what I miss: working class heroes.

Admittedly, Miner Willy didn't spend any time at the coalface, nor have we ever seen Mario up to his elbows in a blocked U-bend despite his plumbing credentials, but both hark back to a time when the popular template for video game characters was a salt-of-the-earth working stiff, facing insurmountable odds, rather than an invincible superhuman warrior.

Even more fascinating is the fact that a great many games back then actually used these working class backgrounds as the basis for their gameplay. Perhaps it was simply that we were so enchanted with the ability to control a little man on the screen, that it didn't matter if the tasks ahead of him were utterly mundane. Most people wouldn't see life as a barman in a dingy drinking hole as a fantasy life worth simulating, but Tapper managed to become a hit all the same. Most kids saw a paper round as a means to an end, or a cruel introduction to the pain of early mornings, yet Paperboy gobbled up coins in arcades on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet while American arcade games would give their pixelated hero an ostensible trade, leave it to the nascent British games industry - then little more than a sprawl of bedroom coders and opportunistic small businesses - to really rummage around in issues of class in gaming.

For example, as surreal and abstract as it was, it's clear that Manic Miner and sequel Jet Set Willy form a cohesive and deliberate work of social satire. In the first game poor Miner Willy risks life and limb to get rich quick. In the sequel, having achieved enormous wealth, his millionaire lifestyle becomes a Kafkaesque nightmare as he's forced to clean his party-wrecked mansion before being allowed to sleep. The soundtrack to his Herculean trials? A deeply ironic chiptune rendition of If I Were A Rich Man from Fiddler on the Roof.

Whether it's a simple act of schadenfreude at the expense of a man who garishly squanders his ill-gotten gains, or a Buddhist contemplation on the way material things drag us down, issues of wealth and class run through Jet Set Willy at a deep thematic level. The planned, but never released, third game in the series makes the satirical intent even more clear: the working title was Miner Willy Meets The Taxman.

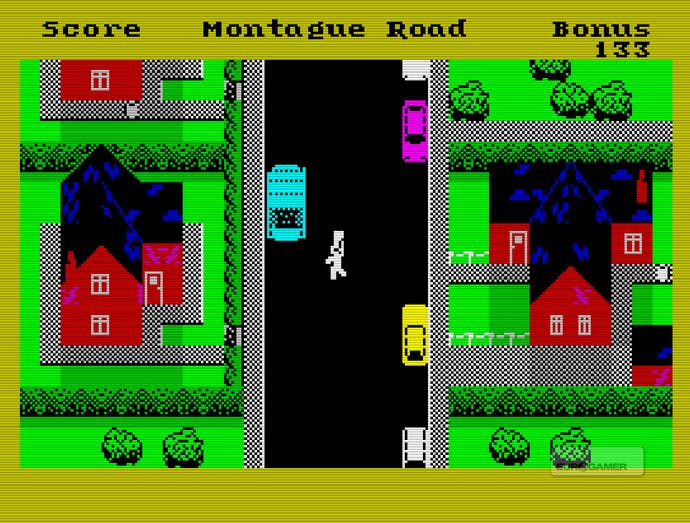

The age-old link between death and taxes also recurs in Trashman, another vintage slice of 8-bit social commentary. As the name suggests, you played as a bin man. Not a bin man in a fantasy kingdom, or ascending a scaffold to defeat an irate ape, but a bin man trudging along a suburban street, frantically collecting and returning bins while a truck inexorably rumbled away from you.

It's hard, unforgiving work, made all the more difficult by reckless motorists who will happily kill you as you hurry from one house to another. Do a good job and residents may offer a tip, triggering a text prompt warning Trashman about taking untaxed cash payments. This was an era when even the in-game bonus comes with a stormcloud reminder about its ultimate cost.

We're so used to games being about cathartic escapism that some of these titles now seem wilfully bleak and depressing. Consider Mrs Mopp, a Speccy obscurity in which you played a harried housewife, doomed to forever clean a variety of respawning household refuse from the floor. Let things become too cluttered and it all becomes too much for the poor woman, her state of mind slips from "fit" down to "exhausted", eventually leading to a nervous breakdown as she flees the family home.

Thankfully there was just one way to keep her flighty tendencies in check - by guzzling cooking sherry. Depression, alcoholism and domestic misery, all served as a brightly coloured collect-em-up. This was what passed for fun in 1983.

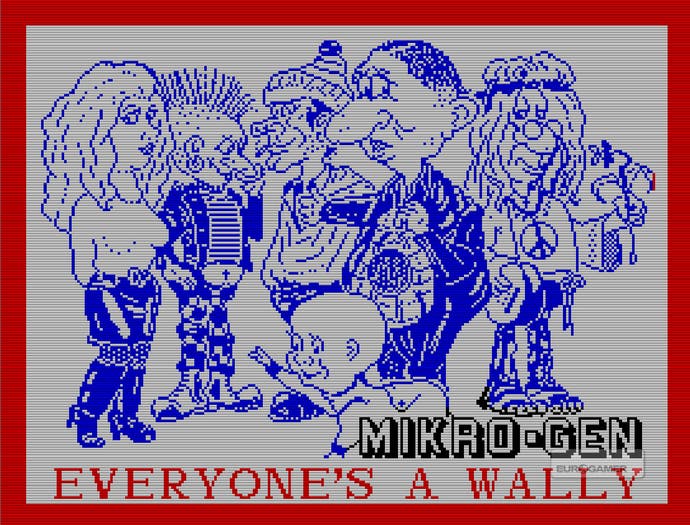

These themes of thankless graft in exchange for small fleeting comforts found their perfect expression in Mikro-Gen's fantastic Wally Week series, a wry and melancholy little digital saga that often plays like an interactive Alan Sillitoe novel with surreal arcade flourishes.

In the first game, Automania, your job is simply to help downtrodden Wally Week get his work finished, assembling a series of cars even as geometric shapes, tools and tires spin and bounce around the workshop trying to kill him. Complete a car and you're "promoted" to do exactly the same thing for a different model of car. Mockingly, the cars go from a Citroen 2CV up to a Rolls Royce, a nimble echo of the social ladder Wally can never ascend.

In the sequel, Pyjamarama, you play as Wally's astral body, roaming his house and trying to fix his alarm clock so he won't oversleep and be late for work. That's the best outcome - Wally gets to be woken up early to go back to that hellish car factory. There are no grand celebrations in Wally's world, just a constant treadmill of duty and responsibility.

The third title, Everyone's A Wally, was a veritable epic and the first game to offer multiple playable characters. Wally is now a handyman, but we're also given control of his wife, Wilma, and his friends: mechanic Tom, plumber Dick and electrician Harry. All have their own mundane tasks to complete, with the ultimate goal to simply open the safe that contains their wages and go on holiday. In an allegorical twist of breathtaking sadness, any contact between Wally and his infant son, Herbert, drains his energy. The inclusive title doesn't even leave any room for emotional distance: you're just like Wally, it says. Deal with it.

These games are just the tip of a wonderfully miserable iceberg, a strange and forgotten style of gaming that filtered everyday drudgery through the sparkling prism of computer games, transforming the soul crushing banality of ordinary working life into whimsical entertainment. You're not saving the world, or avenging some great injustice. Best-case scenario, you're simply getting by, keeping your head above water and the wolf from the door.

That such small victories were considered ample incentives for what were, at the time, popular and critically successful products is hard to believe now. The economies of scale have pretty much eradicated this strain of cultural reflection from the games medium. No major studio is going to spend months and millions on a game about a henpecked manual labourer struggling to make his next payday, and that's a shame. We've lost something there. Something important and quietly powerful, and something that games need to reclaim if they're to be a valid form of creative expression in the 21st century.

I don't believe it's a coincidence that Jet Set Willy was released in the age of the yuppie, or that Wally Week's quixotic quest for a small sliver of financial security occurred while Thatcher was in Downing Street.

Even if the creators of these games only ever intended for them to be a bit of fun, and their limitations were based on available technology rather than political commentary, the cumulative effect is still revealing. Just as genre entertainments like Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Night of the Living Dead were grisly reflections of an America mired in Vietnam and civil rights strife, so the stoic breadline plodding of the 8-bit working class heroes mirrored a British society where the honest toil and trade of old was crumbling under the weight of rapacious bankers and stockbrokers. They were games that spoke to, and about, the time and place they were made.

Master Chief and Nathan Drake are all well and good but, as arch-miserabilist Morrissey famously sang, they say nothing to me about my life. Where, then, are the gaming heroes who will represent the inner struggles of the recession generation?