Searching for a video game hero

Or, why Dale Cooper is so hard to beat.

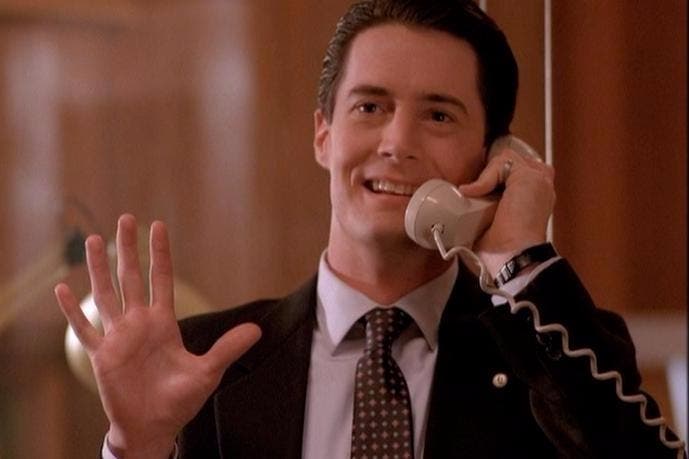

My favourite moment in Twin Peaks - I've just finished rewatching the first two series in readiness, and I cannot believe I am typing this, for the arrival of the third - is the start of episode one, season two. That groaning soundtrack kicks in and we're back at the Great Northern Hotel. Cooper has been shot, and yet Cooper survives, neatly arranged, arms out, on the floor of his hotel room. A little blood but not too much: a sense that he's going to make this. Big relief for a twelve-year-old fan.

This scene is played as comedy, I think, which in Lynch stuff is never purely comedic. An ancient room service guy appears with the glass of warm milk that Cooper ordered before he got plugged. They have a wonderful exchange in which they are both talking at cross purposes. A crucial phone call is ended by the doddery bellhop, and then the moment, my favourite moment in this, my favourite moment, when the bellhop gets him to sign for the milk. "Does this include a gratuity?" asks Coop. You get the feeling he would never sign without a gratuity.

Almost thirty years later, and I never pass up the chance to ask if something includes a gratuity. I never pass up the opportunity to give someone a solid thumbs-up, or to talk to people I have just met as if they might be the single thing in my life that has been missing up until now. I am one of those people who has always had heroes, but at the top of the list, sharing a throne rather awkwardly with Gomez Addams, is Dale Bartholomew Cooper, Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It was love at first sight: here was someone capable, mysterious, gloriously, thrillingly intuitive. But not just that. Here was someone who, for a twelve-year-old watching a scary TV series for the first time, might be emulated. Dale Cooper wasn't just a character in a TV show. He was a template, I am not even remotely ashamed, for the sort of person I hoped to become.

Long story short: mixed results. Thirty years later I am not a crack shot or a brilliant deductive thinker. I am not as handsome and alien as a store mannequin. I am clumsy, often stupid, and I look - forgive me if you have heard this before - like the protagonist in a Smallville-style show about the early life of Father Christmas. Still, Coop has always been there as a guiding hand when I am wondering how to proceed. Be kind, he says. Be gentle. Be curious, even if it makes you look a bit curious as a result. Oh yes, and enjoy food to the max.

Cooper has been a good hero, in other words. My early self chose extremely well. And it makes me wonder, inevitably, about the other things I was doing at the time Twin Peaks first aired, and why I never chose my heroes from anywhere other than television and the occasional book. Video games are all about heroes, but they seem strangely lacking, for the most part, in people who might actually become your personal hero. There was no danger, in 1989, of Wonder Boy leaping off the tube and becoming a person I wanted to emulate. While my sister and I loved Mario and Link, we did not wonder, for extended periods, about what they did when the cameras, so to speak, finished rolling. We were obsessed with the games. We were obsessed with controlling Mario and Link and Wonder Boy, but we did not really want to be them. Not the way I wanted to be Dale Cooper.

And this has not changed that much. I've played hundreds of games, and been cast as heroes in a majority of them, and yet they do not carry across in the way Cooper did. To put it another way, I have loved games but the characters have never become love affairs. In part, I think this is because of the question of agency: games characters are vessels for you to fill as you play, so there is sometimes a lack of specifics, or of the right specifics, that can make a character like Cooper, or Gomez Addams, such an object of fascination and speculation - core elements that pave the way to hero worship. The element of performance, until very recently, was also lacking, and game designers over the years have had to play to a vast audience who they have had to suspect all want largely the same things. Power fantasy figures rarely work as heroes, I suspect. Turns out there is nothing terribly heroic about a very obvious hero.

Over the last few years, however, this has changed. I appreciate everyone will have their personal favourites - and I appreciate that many people will have a long daisy-chain of personal heroes linking together everything from Super Mario 2 - Birdo was pretty great, all things considered - through to Metal Gear Solid and John Woo's Stranglehold. (Bit of a cheat that one; Inspector Tequila was a hero in a film before he was a hero in a wonderfully kinetic blast-'em-up.) Of late, though, the heroes I can get behind have started to emerge in gaming, and it is lovely to have them.

And they are so unexpected. Max Caulfield! Halfway through Life is Strange I realised that Max was something special: a character trying to navigate a tricky world with kindness and honesty. BUD in Grow Home. (Sorry, I appreciate that Grow Home and I really need to get a room.) Here was a guy succeeding with real, clumsy character, in a world in which he did not seem likely to succeed. There is something about seeing BUD, very small, hanging from a mountain, so very big, over a huge drop that will kill him if he slips. I have been in desperate situations in many games, but never in the company of someone who seems so vulnerable.

Maybe vulnerability is the key to it, really. Maybe we - or maybe this is just me - are drawn to heroes that seem to need something in return. Cooper, for all his confidence, seems rather lonely on my second, recent viewing of Twin Peaks. Gomez would not have been so relentlessly optimistic without his wonderful family. He would be lost without them, and even in his maddest happiness, he seemed to broadcast this. Max is at that brilliant stage where you are looking for a place in the world, where you are trying to work out who you are going to be. Even BUD needs a leg up and someone to make sure he doesn't get hurt out there.

Video game heroes have always needed us, of course. They need us to push forward on the stick, for one thing, to set them off on their next adventure. But only recently, to my eyes at least, have they started to feel like they really might need us. Complexity in character starts with a crack in the armour. It starts with something that is missing - something that cannot be found on the upgrade tree.