Seeing farther: the advert that changed the games industry

Electronic artists.

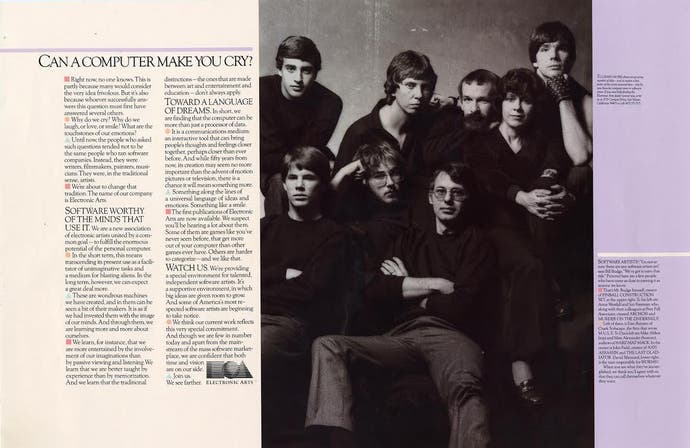

The photo is black and white, and slightly soft-focused. There are eight people dressed in black, lounging together in front of a paint-splattered roll of tarp. Their faces are young and rock star serious.

They could be actors or musicians, but they're not. They're game developers - or 'software artists' as the accompanying text would have it. The image is part of an advertising campaign for the fledging publisher Electronic Arts - and accompanying the photo are two possible slogans depending on where the ad was placed. One says 'We see farther', the other, much more memorably, is 'Can a computer make you cry?'

This was how EA advertised itself in 1983.

Nowadays, asking 'can a video game make you cry' has become a cliché, a joke - it's up there with 'when will games have their Citizen Kane moment' and the dreaded 'are games art' on the list of eye-rolling questions thrown by the mainstream media at narcissistic creative directors (and vice versa). But this was the beginning of the 1980s and the industry was a very different place. Games were still seen as novelties; you played at arcades or in bars, or you bought a console for the kids. Nobody knew who made these things and nobody cared; nobody really saw Pac-Man or Space Invaders as anything other than fun. The very idea of actually publishing, manufacturing and distributing computer games as serious commercial products was in its infancy.

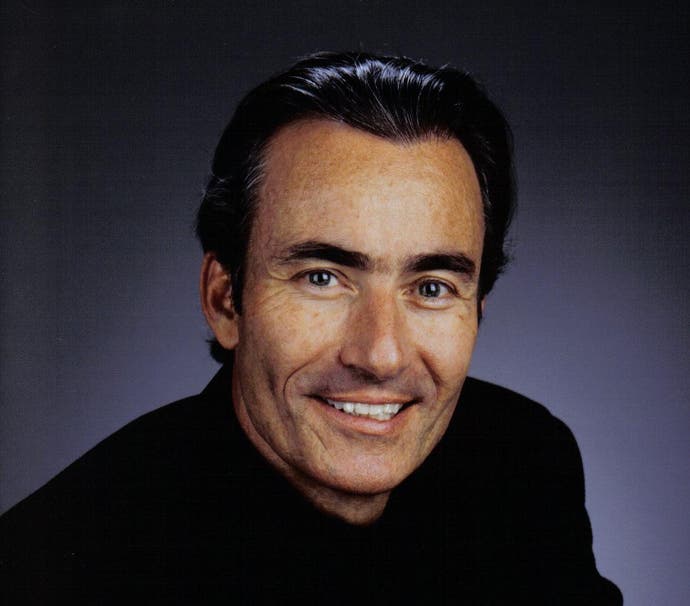

So to book out a studio in San Francisco one summer morning, and to hire Norman Seeff, one of the greatest rock'n'roll photographers of the era to shoot an advert? It showed considerable ambition and foresight. But then, that was Trip Hawkins all over. Sharp, determined and oozing charisma, the Electronic Arts founder had been at Apple since 1978 and as director of strategy and marketing he'd helped transform the company from a maker of hobbyist computer kits into a serious manufacturer with a unique brand identity. It was there, working directly with Steve Jobs, that he realised something important about emerging industries.

"While at Apple, I came to appreciate the power of innovation reference points," he says. "You are doing something new but you look for things that have similar issues and needs, to see what you can derive. Apple succeeded in using the consumer electronics industry as a reference point for its channels of distribution, sales, dealer agreements, promotion, packaging and other factors. I realised that EA could benefit from this same 'reference point' approach."

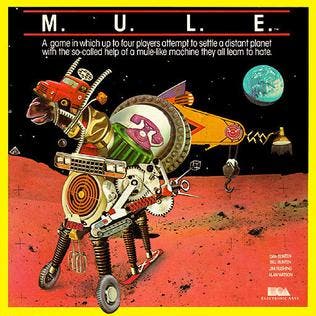

So when Hawkins set up EA in 1982, he needed his own reference point - a similar business he could draw ideas and attitude from in order to market his games. He had already signed up a bunch of talented designers, including graphics whiz kid Bill Budge who'd made a huge impact with Raster Blaster on the Apple II and Danielle Bunten Berry, who wrote the ground-breaking multiplayer title M.U.L.E, but he wanted something extra to make EA stand out. "From the beginning at Apple, I was working with great creative people including Jobs and software engineers like Bill Atkinson," he says. "It dawned on me around 1980 that they were complex and difficult like divas, and yet powerful artists worthy of special treatment, and that great software development could be organised and managed like a movie. Hollywood then became the critical new reference point and many key ideas just rolled out of my head once the framework was there."

The really big idea, he says, was promoting game makers as 'software artists' rather than programmers or engineers, taking them into a whole new cultural gamut. "Everyone I talked to during the first year got excited about it," he says. "They could understand the power of this concept and it then carried over easily into marketing execution. It was obvious we could get much more attention by becoming The New Hollywood."

Enthralled with this idea, Hawkins arranged a meeting with a group of young advertising copywriters, Jeff Goodby, Andy Berlin and Rich Silverstein, who at that point were working for the award-winning Hal Riney & Partners, but looking for their own freelance work. "Andy Berlin spent several hours listening to my ideas and plans and direction and their team then did some great execution including the artist poster," recalls Hawkins. "They'd not yet formally organized a new advertising agency and we became their first real client." Goodby, Silverstein & Partners would go on to make the classic 'Got milk' and Budweiser Lizard commercials, but they honed their attention-grabbing conceptual skills on EA's campaign.

"I remember the day of the shoot very well," says David Maynard who'd joined EA straight from Xerox. Maynard was an old school coder, a member of the first Computer Science class to graduate from U.C. Berkeley in 1969. Through the 1970s he'd worked with Doug Engelbart's team at the Stanford Research Institute using PDP-10 time-sharing computers running the formative Tenex operating system. Here he got exposed to early text-based based games like Hunt the Wumpus and Adventure by Will Crowthers and Dan Woods. In the late 70s he joined a group at Xerox PARC working on the Alto, the first personal computer with a built-in ethernet connection; he wrote a Breakout clone just to get used to the hardware. He then bought an Atari 800 to design his own game, Sumo Worms, ("based on a Martin Gardner Scientific American article about 'Patterson's worms," he explains). Then he met Trip, left Xerox and, one morning in 1983, found himself in San Francisco in the suffocating heat, waiting to be photographed by the man who counted Ray Charles, John Lennon and Debbie Harry among his hundreds of subjects.

"It was a rented studio and they flew Norman Seeff and two assistants up from Los Angeles," he says. Also in the picture alongside Budge and Maynard were John Fields, the creator of Axis Assassin and The Last Gladiator, Jon and Ann Freeman, creators of Archon, Michael Abbot and Matt Alexander who made Hard Hat Mack and Bunten, who had to be flown in from Little Rock, Arkansas. "The shoot started around 10 in the morning and went to at least three O'clock in the afternoon," recalls Maynard. "It was warm in the studio space and the shoot was exhausting. At one point John Fields actually fainted."

The developers had all been told to wear black turtleneck tops - the look was considered cool and edgy and the fact they were all wearing the same thing made it feel like a rock band shoot - a notion Hawkins and his marketing man Bing Gordon were keen to perpetuate. "EA's PR firm Regis Mckenna had people there - all attractive young women -sort of covering the 'event'," says Budge. "I think it made everyone feel pretty special. I remember Trip giving me some personal style and grooming tips. It did feel strange to be getting this treatment for a photo shoot - I don't think I was aware of what the photo would be used for."

It's Budge in the top right-hand corner of the photo, famously wearing a single studded fingerless glove. "Someone from Apple was hosting a party that evening with a punk rock theme," he says. "My friend Susan Kare, the famous graphical designer, took me to some stores in the city where I picked up a sleeveless black sweatshirt with studded arm holes, a studded black leather belt, and the notorious 'glove'. It was just a costume in my mind, not something I would normally wear. I arrived at the photo shoot with the costume in a shopping bag. Somehow the photographer found it and insisted I put it on. Everyone thought that was a good idea and I was persuaded."

With the photos taken, development of the adverts themselves began. Bing Gordon employed Nancy Fong, a young production manager from white collar advertising firm McCann Erickson, to oversee the process. "I worked with Rich Silverstein, the art director of Goodby, Berlin & Silverstein, on the production," says Fong. "It was a master class. I remember how particular he was on every detail, down to the smallest percentage of cyan, magenta, yellow and black on a single bullet point. And Andy Berlin's copy was like nothing I'd ever read before in an ad."

Sitting under the 'can a computer make you cry' header was a 500-word mission statement on how Electronic Arts understood the burgeoning era of home computer technology; how it saw the potential to move beyond building spread sheets and blasting aliens. "In short," the copy concludes, "We are finding that the computer can be more than just a processor of data. It is a communications medium: an interactive tool that can bring people's thoughts and feelings closer together, perhaps closer than ever before." Considering we're still talking about the emotional and social possibilities of games in 2018, an ad like this was a miracle in 1983.

It was also expensive as hell. Creating the adverts cost a fortune in itself, but then EA made the decision to place them in publications that moved beyond the specialist computer and gaming press. "As a child, one of my life goals was to be published in Scientific American," says Maynard. "So when Bing Gordon was talking about the upcoming ad, I suggested they run it in there." Gordon went for it. The ad ran across pages 192-193 of the September 1983 Issue. "That placement was probably our entire marketing budget for the year!" laughs Fong.

But did it work? "Everyone thought the messaging was clever but, 'out there'," says Hawkins. "The ads didn't sell games and I'm sure my more practical competitors thought we'd be dead within months. The important thing is that the artists loved it and appreciated it, and all of them became more willing to consider working with us."

This was definitely an important element. In an industry that had little respect for developers, where a company like Atari deliberately obscured the creative talent behind its games to avoid headhunting, the fact that EA idolised and promoted its artists made a big difference to upcoming designers and coders. As Maynard puts it, "I mostly agree with [the blogger and computer historian] Jimmy Maher who wrote 'the most enticing thing that Hawkins offered his developers, and by far the most remembered today, was an appeal aimed straight at their egos: he promised to make them rock stars.'"

Budge agrees. "For most people at the time, games meant Pong - the ads promoted the idea that much more would be possible. My friends at Apple and in the game industry would make gentle fun of it but I think it may have inspired proto-programmers to want to work in games given how cool this made it look."

But it was more than that. The 'can a computer make you cry' advert also laid out a new philosophy for games; a philosophy that looked beyond the age of arcade thrills to something more profound. "Trip realised that the increasing power and affordability of home computers would create the opportunity to add greater depth to the experience," says Maynard.

This was EA in the early 1980s - making strange interesting games like Worms and M.U.L.E, filled with the excitement and hope of a start-up. When Nancy Fong joined it was 20-people squatting in a single-room office in the city of Burlingame, just south of the San Francisco airport - an office owned by one of the company's early VC funders. They had no games on release yet and no one to make the packaging for them even if they did. "By that afternoon, we moved to a larger space down the peninsula and I had convinced a couple of my contacts to extend credit and become our first printing vendors," says Fong. The company was Ivy Hill Packaging in LA, one of the largest printers of record album covers in the country - Trip's other big idea was to package his games like albums, complete with beautiful gatefold sleeves. Once again, he wanted his games to be seen as cultural products, not technological toys sent out in ziplock bags. The ads were the calling card for a philosophy that would shape the company's early years.

"We See Farther was the headline of our manifesto that hung in the lobby of our first couple of offices," recalls Fong. "It was about the vision of who we were, where we were going, and how we were going to work. Our common goal was: 'We seek to fulfil the enormous promise of personal computers'. One of my favourite company T-shirts had the copy 'Software worthy of the minds that use it'. We resurrected that line in the Annual Report of our tenth year."

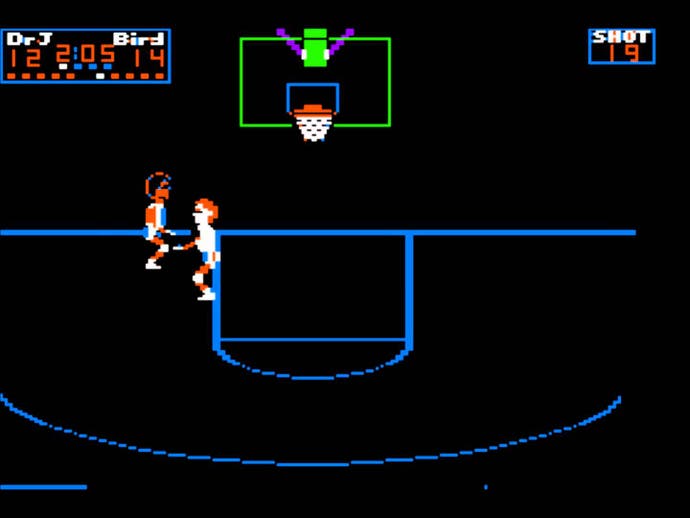

The EA adverts changed the industry because they showed the wider potential of games, they flirted with new audiences, they promised new experiences - they also signalled the growing ambition of the industry. Later in 1983, the publisher released the basketball sim Doctor J and Larry Bird Go One on One, kickstarting the EA Sports concept that would define the company and make it millions - but it would all somehow emanate from those double-page spreads.

As for the software artists themselves, they felt elevated by it too. Budge and Bing Gordon went off on a publicity tour, appearing on TV and making personal visits to computer stores around the country. "We were trying to establish programmers as rock stars, but without much success," muses Budge. "In some places we visited, it was more like hobbyists getting together. At Lechmere in Boston, they saw us as representatives helping sell merchandise, so they actually insisted I change out of my jeans and T-shirt programmer gear. Bing took me shopping and bought me the cheapest dressy outfit we could find."

Maynard just appreciated bathing in his new found fame. "I had worked with the researchers at Xerox PARC, which housed some of the most brilliant computer scientists in the world. There were many superstars there - I was not one of them. And yet here I was, with my picture in Scientific American, being called a Software Artist. It was, if nothing else, audacious as hell."