Shakedown: Hawaii review - crime and capitalism in a sunny open world

Bank notes from a small island.

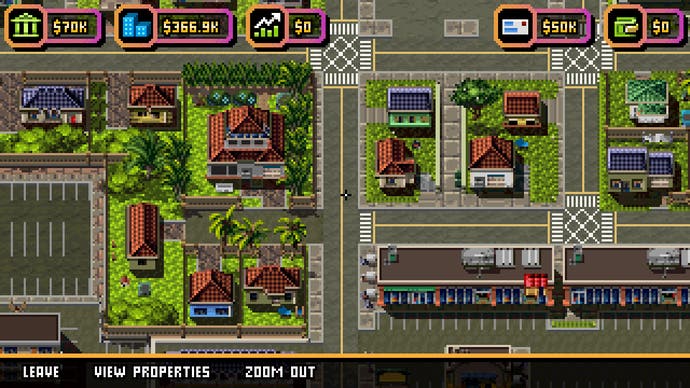

Shakedown: Hawaii is the latest game from Brian Provinciano, whose previous work, Retro City Rampage, de-made GTA for the era of 8-bit consoles and then loaded its open-world with topical memespeak gags and labour-of-love gimmicks. Shakedown: Hawaii is more of the same - more open-world crime, with 16-bit graphics this time, as a trio of characters rebuild a decrepit business empire using deeply questionable tactics. But as well as being a game about stealing cars, running people down, and shooting everyone you meet to pieces, it's also a bit of a clicker.

The more you play, the more you earn. And the more you earn, the more of the map's businesses you are able to buy up, and benefit from their daily revenue. After one real-world day of playing, I owned a fairly small proportion of the map, and I was making about half a million every in-game day. The following afternoon, when I finally hit the end-game and looked back at my stats I owned 334 of the 415 available buildings in town, and I was making just over three million every 24 hours. That's in-game 24 hours, of course. Quite a career I was having.

Shakedown's taken the clicker mentality to its core, I think. Nothing in this game contains much in the way of friction. The storyline is frothy and glib, taking on the myriad annoyances of the modern world, from expensive printer cartridges to the cruel T&Cs on a competition flyer's small print. It's entertaining enough, I think, and if you tire of it you can hold down a button to speed through cut-scenes at double time anyway. And the missions - there are over 100 of them - are short, punchy affairs. You drive somewhere, you shoot someone or punch someone or smash something up, and then you drive somewhere else.

It's astonishingly brisk, sending you from speedboat to jungle shootout to industrial espionage to music recording studio in a matter of minutes. Now and then you'll get a Wario-style mini-game as you pump iron or inject ink into one of those overpriced cartridges. Now and then you'll get a riff on the basic action format that brings a moment to life, too: cutting an enemy's hair rather than shooting them to pieces, stuffing paper down the toilets of a business you want to soften up enough so that they'll sell it to you. Even the game's most outre moments allow you to plough ahead without too much thought, though. Onwards and upwards. Ka-ching.

The satire, which tends to be fairly blunt, is at its best when you're applying multipliers to raise the income of businesses you own, throwing in irritations such as telemarketing and lobbyist fees. The hustle never goes away, it just learns a new vocabulary to hide inside of. Beyond that, the most fun is to be had in the map screen as you slowly turn the whole city into your property, buying in great splurges as new stuff becomes available. It's enormously pleasing.

Moment to moment, it's a breezy action game built around murder and capitalism. Cars are plentiful and easy to handle, weapons range from the basic to the baroque, the odd run-and-jump section mixes nicely with kill-everyone-and-get-out-of-there stuff and you can even shoot from your car if the mood grabs you, which it will, because of murder and capitalism. As an open-world, Hawaii has range and scale if not much in the way of monuments. The top-down pixel-art provides lovely chunky detailing, though, and regular trips to distant jungles and rivers and mines halt the creep of boredom.

It's diverting stuff, and generous with side missions and challenges and all of that jazz. When it's done, it fades from the memory pretty quickly, and, rather than a criticism, I suspect that might be the point of it really. This is drive-thru nihilism with a patina of satire to make the whole thing sing a little more. Onwards and upwards. Ka-ching.