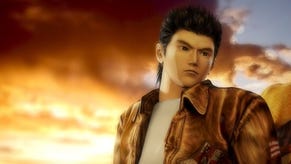

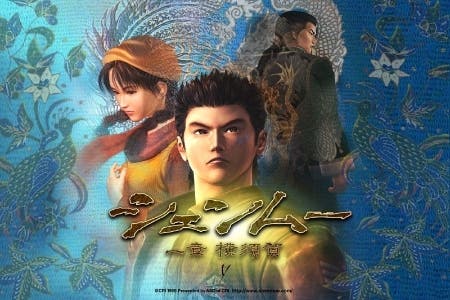

A postcard from Yokosuka: Retracing the steps of the original Shenmue

From the archive, a look back at Yu Suzuki's open world wonder.

Editor's note: Shenmue 3 is not only a thing after its reveal at last night's barnstorming Sony conference, it's already reached its Kickstarter goal. What better time, then, to go back to the original Shenmue in this retrospective piece, first published in 2012, about a day-trip to Yokosuka.

You can't buy a ticket to the Mushroom Kingdom, and there's sadly no package holiday I know of that will whisk you away for a couple of golden weeks in the kingdom of Ivalice. You can, however, take a train to one of gaming's great locations - although it's hardly the most fantastical of places.

45 minutes up from Tokyo's Shinagawa station on the Keikyu line is Yokosuka, one of the Kanagawa prefecture's more unremarkable cities. It's just beyond the point where the clutter of Tokyo thins, and just before the pastoral countryside comes into focus; an industrial hub, its shores are consumed by a US naval base, its outskirts hemmed in by factories while its centre is a world of humdrum shopping.

There are malls - there are plenty of malls - but they're not the kind of sparkling towers of commercialism that you'll find in Shinjuku. They're grubbier, more run down and crowded by members of the US Navy whittling through their shore leave. They're the kinds of buildings that are visibly bored - all sullen, sagging concrete and featureless, clinical walkways.

This likely isn't the Japan you've ever dreamt of, nor the one you've ever played through - it's not the neon fantasy of Tokyo, the cherry blossoms of Kyoto or the drunken reverie of Osaka. It's Slough, or it's Aylesbury; the kind of dreary urban outskirts where time swills slowly. It is, in short, a melancholy, run-down place, and the perfect backdrop for a tale of disaffected youth.

Before 1999, it's probably not the kind of place you'd expect to find Yu Suzuki. This is a man who's sent Ferraris racing across Hawaiian paradises, sent jet fighters streaming across Pacific blue seas and had martial artists fight in mystical, pristine Japanese courtyards. His work's defined by brazen spectacle, which is something that's in short supply on the sombre streets of Yokosuka.

Perhaps it wasn't always going to be this way. Before Shenmue came to be the poster child of Sega's Dreamcast - and the very embodiment of the console's promise, potential and its subsequent failure - it was something very different. It was originally imagined as an RPG spin-off for the Virtua Fighter series with main man Akira taking the lead role, and it was first destined for Sega's Saturn.

But something changed. Development switched over to the Dreamcast, and an emphasis was placed on an original story to be told over multiple episodes. That story would lead to places that have remained with Suzuki for long years, but it's the protracted severance of the Shenmue series that perhaps makes the very first instalment feel so special.

I've always preferred the parts of super-hero films before the superpowers emerge, when our stars are bumbling through their day to day existence; give me an afternoon at the Daily Planet over one spent battling across the Grand Canyon any time. It's Shenmue's depiction of the ordinary that make it so extraordinary; here's a multi-million dollar folly that's at times about nothing more than killing time in a dead-end town.

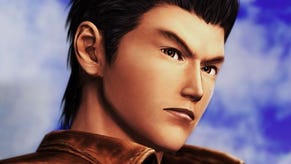

It's set up as a tale of revenge, although if that's the case it's a fairly limp brand of vengeance that Shenmue wields. And besides I don't think the first game is about that, really. It's about grieving, and it's about the long, muted and grey period of mourning. It's about, as Ryo bluntly repeats to the housewives and shopkeepers of Yamanose as he first tries to piece together the circumstances surrounding his father's death, the days when the snow turns to rain.

Ryo's mourning is never explicit, but it spreads out to every part of the world he inhabits. It's mirrored in the concern of his housekeeper Ine-San, and his housemate Fuku-San, and it's there in his distant relations with his would-be lover Nozomi. And in what's quite likely an act of brilliant chance, it's there in the disembodied, half-hearted English dub that inadvertently underlines how detached Ryo is from his surroundings.

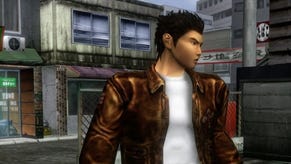

You're on the trail of killer Lan Di, working your way through the underworld and getting into impromptu scraps with a criminal culture that sits somewhere between the travel-worn American sailors and the gangs that operate out of Yokosuka's alleyways, but that's not the real story, and it's not the real mystery that's begging to be unraveled. That real tale is of Yokosuka itself.

Yu Suzuki's a designer who's always thought in 3D; even before he'd struck a deal with Lockheed Martin to secure the chips that would make 3D gaming a reality with Virtua Fighter, he was falsifying horizons with Out Run and Afterburner. Suzuki games are all about drawing you into a world, whether it's through F355 Challenge's three-screen cabinet or the hydraulics and crafted plastic cockpits of his '80s arcade games.

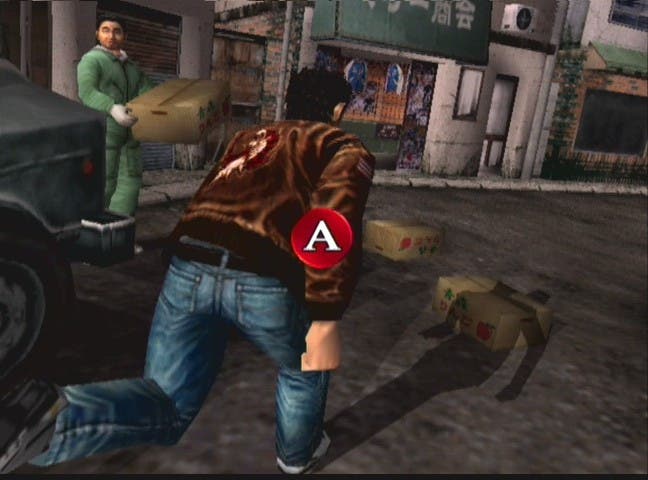

Shenmue didn't have the luxury of a bespoke cabinet, of course, but it did benefit from a gimmick that was just as effective. Suzuki never really referred to the game as an adventure or an RPG, and at the time the gaming lexicon hadn't really extended to include the open world term that would have fitted it so well. Instead, Shenmue was pushed as something new: as a FREE or Full Reactive Eyes Entertainment.

It was a catch-all tag, an umbrella statement for all the different systems that made Yokosuka tick: the weather that could see dark clouds forming over Yamanose before they burst over Yokosuka's docks, the hundreds of fully voiced, fully written characters that would criss-cross the streets as they acted out their daily routine and the fully operational arcade, shops and bars that are around town.

By current open world standards - in fact, by any standards - Shenmue's Yokosuka is a miniscule world; it's a suburb, a handful of city streets and a sprawling yet largely featureless dockside. But what Shenmue has, and what it has in abundance, is detail. The kind of detail that can send you rooting through drawers of Ryo's house, or the kind of detail that has you deliberating on what kind of cat food's best for the stray kitten you're taking care of. It's the kind of detail that has idle conversations with otherwise non-descript non-playable characters revealing the inner lives behind each and every door.

Which is why Shenmue, for me, was never really about avenging Iwao Hazuki's death or unearthing the Chi You Men, and it wasn't even ever really about looking for sailors. Somewhat fittingly for a game with a sullen teen at its heart, it was about that most adolescent of pursuits: it was all about killing time.

And Shenmue's a game that's constantly asking you to wait, sending you to an objective only to tell you it's unobtainable for another few hours. It's a game that's constantly asking you to go and find something else to do, until it reaches the point that the downtime becomes the game - and until it's about nothing more than finding how to while away an afternoon in the city of Yokosuka.

There's no real urgency in place, and its grand arc offers a gentle tug rather than rudely shoving you along. Too often in open-ended, open world games there's a conflict that's I've never been able to resolve: you've the burden of saving the galaxy on your shoulders, but the designers expect you to stop in your tracks to resolve a lover's tiff between two people you've never met before.

In Shenmue, Yokosuka's stories are much more enthralling than Ryo's own; there's the chef at Funny Bear Burgers, a former banker who quit to pursue his culinary ambitions, or the elderly widower Hattori who stands outside his sports shop, sending a drive down an imaginary golf course each and every day. And so Shenmue becomes a game of eavesdropping in between chores, killing time at the arcade or expanding your capsule collection while silently stalking non-playable characters.

It inspires an intimacy with its surroundings that few other experiences can really attain, and that's what makes a pilgrimage to Yokosuka so chilling. I've etched every pixel of OutRun 2's tarmac into the wet flesh of my memory, and there are parts of Hyrule I know better than my own living room, but I'll likely never experience the strange synapse snap of being confronted by them in real-life.

I went there on a stolen day during my first visit to Japan, a two-week tour with my girlfriend who'd spent two years living in and around Tokyo. Japan's an intimidating place for the first-time tourist, so I spent much of those two weeks being guided around, terrified of getting lost in a world of indecipherable streets and signs. Yokosuka offered some kind of relief.

As you leave the station it's a nondescript network of roads, but slowly the details come into place; there's the quiet suburb of everyday houses that then dips down a hill, leading to a handful of streets that are given over to shabby bars and restaurants. There's the car park that sits somewhere between the highway and the high street, and the big red store on the corner (which in reality is a launderette rather than a convenience store).

And then there's the moment when it all comes into sharp focus: Dobuita Street, a gauntlet-run of gift shops hawking garish tat and sukajyan. By the time I got there I was walking step-by-step with Ryo, working through instinct to find Kurita-san's military surplus store and Mary's Patches & Embroidery and walking through the streets with the knowledge of the local that Shenmue had made me. Having been led around Japan for two weeks, I'd become the guide in a foreign land.

The game's gone on to become a relic, a reminder of Sega's long lost status as dreamcatchers and of the Dreamcast's status as the ultimate cult console. In Ryo's quest for vengeance there's what's likely to remain gaming's greatest untold tale, but for me in Shenmue there's something else. In the grounded fantasy of Yokosuka, there's proof positive that video games can transport you wholesale to distant lands and faraway places, no matter how drab they may be.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)