Should More Indie Developers Be Saying 'Just Pirate It'?

Exposure marks the spot.

People have differing ideas on the subject of piracy, but most would never step over the line and support it. Someone who advocates piracy is labelled devil spawn, promptly whipped and then lemon juice squeezed into the sores. In short, it's the internet's most heathen of crimes. If you were to tune into the chatter in the indie game scene right now though, what you may hear is a radically different viewpoint. Pirate radio, if you will.

It's more than hot air, too; actions are being made in an attempt to tap into the benefits of piracy. You will more than likely know the two highest profile contributors to the argument: Edmund McMillen and Markus 'Notch' Persson, both of whom have stood against the grain for years now but more recently told followers on Twitter to pirate their games when they could not or would not pay the asking price for them.

Predictably, there has been a backlash to this carefree outlook on piracy, with a few heated debates erupting between developers. The question is whether there is actually any worth in encouraging piracy for a small profit-driven developer. Instinct tells us not, but there is evidence that suggests otherwise.

tinyBuild's No Time To Explain saw a rise in sales after the developer had purposefully leaked it on to Pirate Bay. The developer actually embraced piracy by making a pirate-themed version of the game intended for users of the targeted website. "You can't really stop piracy," tinyBuild explained to Torrent Freak, "all you can do is make it work for you and/or provide something that people actually want to pay for."

According to the developer, the pirates saw the joke and were appreciative of the effort enough to then buy the full game in some cases. It's a gimmick, but it's a gimmick that worked - and another developer followed a similar path with similarly positive results.

Jorge Rodriguez of Lunar Workshop posted a very clear message in the midst of the anti-SOPA protests on January 18th 2012: "I encourage everybody to pirate Digitanks for free".

It was a simple protest - Rodriguez says that it was never his intention to garner attention from the press as became the case, nor was he attempting to boost sales. Though that's exactly what happened.

"[After offering people to pirate DigiTanks] there was a bump in sales. I attribute it to more people hearing about it, the more people have heard about a game, the more people will buy it. If a certain number of people buy it and twice as many people hear about it then twice as many people will buy it. It's just plain numbers really."

It's another gimmick, although it's another successful one; it earned Digitanks a lot of attention from press and many players seemed to admire the developer's stance. While there's no solid evidence to suggest that piracy leads to more direct sales of a game though, it does suggest that exposure can lead to more sales - that, at least, is logical.

It is this idea - that piracy can lead to exposure - that Markus 'Notch' Persson sees as an opportunity. "One could see [piracy] as a big equation," he told us. "How much money do you lose on each pirate (bandwidth cost for the game, for example)? How many friends does each player (pirate or legitimate) talk to about the game? How many pirates can you convert to paying customers by doing a game update? How much is brand awareness worth in the long run, for future games and future projects?"

One person who has clashed with Persson's views is Cliff Harris of Positech. Harris acknowledges that in an ideal world Persson's belief would be a valid way of thinking, although he's not so trusting of pirates.

"The positive effects of [piracy] are surely outweighed by those people who live in the relatively affluent west," he told us. "They have broadband internet and a decent gaming PC (all paid for) but will make the argument that they are as poor as the kid in a third world country. People do an amazing amount of dodgy rationalising when it comes to justifying getting free stuff."

Persson's more optimistic, believing that piracy can, in the long run, be beneficial to smaller game developers. "For a small studio, things like brand awareness are very valuable," he says, "and the costs of piracy are very low. People will talk about the game, you keep working on it, and you keep getting opportunities to convert pirates. And even if you don't, you will probably have a much larger player base by the time you move on to your next project."

Harris responds by bringing up the costs that profit-driven developers have to face. "What really helps indie developers is people buying the games," he counters, "and not just for ten cents. I can't pay my rent with goodwill from pirates, however well-meaning, and ultimately indie developers only get to make a second game if the first made money."

What indie developers really need are two things: sales and exposure. The problem is that one does not necessarily lead to the other. If you want to gain exposure, one way is to release your game for free, but this goes against the idea of earning sales unless people want to donate voluntarily. But as Harris points out, there are many costs that a company has to cover in order to operate, presuming that they are not a hobbyist.

This is why there does seem to be some worth in promoting or otherwise engaging piracy if it can lead to sales. For smaller developers attempting to make a profit from their games, piracy is something they usually have to face every day - but what do they think of the idea that piracy can be of benefit to small developers?

Ido Yehieli has not long released his debut game Cardinal Quest for $10 with no DRM.

"My relationship with pirates is more apathy than anything; I don't think they do grave damage because with a game like Cardinal Quest I would like to think the real fans would support a one man shop, and I don't have enough publicity for just any mainstream gamer to have even heard of me or my game."

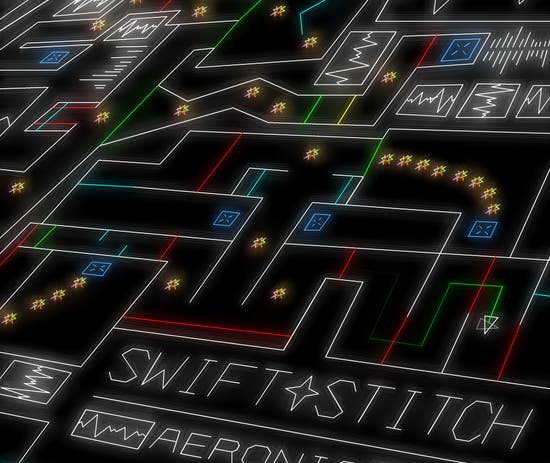

Sophie Houlden has released many of her games for both free and at a price. She conducted an experiment with her most recent game, Swift*Stitch, in which the asking price went up and down over the course of a week, and the results were intriguing.

"If there is something that really is on nobody's radar, then it's not being pirated (they don't have magical knowledge of games nobody has heard of). But a single person spreading the word about your game is a benefit if you ask me, so any amount of piracy could help.

"I probably make it sound like you should just tell pirates about your game, but that's not quite it - just have a demo of your game. It's about having more people enjoying your game and telling friends. Some of those people will pay, some won't. You just have to get more people playing, and the people paying should rise with that if you have a game non-pirates are happy to buy."

Jorge Rodriguez recently invited 'everybody' to pirate his game Digitanks as an anti-SOPA protest.

"I can't stop [piracy] and I probably wouldn't want to - I care more about people playing and enjoying my game than making every last buck. But that said I do hope people remain honest and pay for the game."

The general consensus in the indie game scene is that piracy can help with driving exposure and potentially, in the long run, sales as well. It's about neither supporting nor fighting against it, but perhaps engaging with piracy in creative ways such as tinyBuild did.

With the abundance of bundles, alphafunding models and dedicated digital store fronts, the most essential thing is to get people playing your game. If this means telling people to pirate your game when they won't fork out the cash, then advocating piracy may well be an option.

Being able to point those interested in your game towards a demo, or perhaps a discounted alpha version would seem more beneficial though. But what are the limits that a developer should go to in order to get people playing their game? Well, that's entirely up to them, and to their faith in their players.