Sim Society: DARPA, serious simulation, and the model that stopped a flood

When will the levee break?

The science of prediction has a long history of seeking answers to seemingly impossible questions. What will the weather look like next month? Will the stock market dip in the next hour? In 1928, studies were being done by the United States government to find an answer to another hard question, one that might save lives: Can you predict the nature of a river before a flood?

A year before, across Midwest America, spring started when the snowpacks from the previous winter began to melt and run down into the Mississippi river. Unlike previous years, the change in season was met with an unexpected rain. It rained through the start of January, and continued for the entire month, slowly filling the Mississippi, which rose little by little. By February the levees around the river were starting to strain with the rising water. Three months later, a whopping 145 levees around the Mississippi failed and 10 states were underwater. The flood would span 27,000 square miles and leave over a thousand dead.

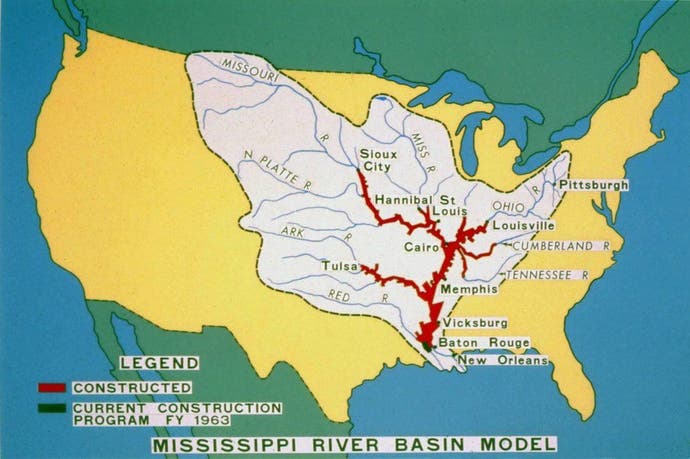

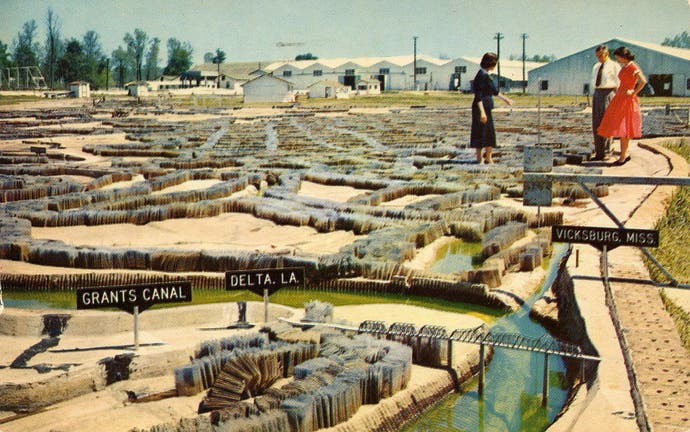

In an episode titled America's Last Top Model, tha podcast 99% Invisible tracks the multi-decade-long development of one answer to the question of what a river might do in the face of unprecedented rain. The Mississippi River Basin Model is a physical reconstruction of the whole Mississippi river, designed to a 1/2000 scale. Imagine! 1.25 million square miles shrunk down to 200 acres of land. The model was so sprawling it could only be viewed in full if you climbed up to the top of an observation platform four storeys high. Yet it was small enough that in photographs taken during its construction, the compact man-made river makes its inspectors look mammoth by comparison; they lean over the model levees like inquisitive giants.

Just how well can a man-made model of the Mississippi predict the real thing? Well, with surprisingly high accuracy, it turns out. By 1952, the model correctly predicted which levees would fail and overflow near Sioux City, Iowa - accurate within inches of the real river. By the early 1990s, the model was credited with saving millions of dollars in flood damages, and one would imagine a few lives too.

But it's also expensive. And in an era fuelled by computing power, real world models like the Mississippi River Basin have become less fashionable.

Video games like SimCity have prepared generations of gamers like me to look at the world from a top-down perspective, an odd skill that I'm not sure would come as naturally had we grown up in another time away from simulation games. Seemingly useless life lessons - for instance, a mismanaged SimRoad can lead to SimSocietal anarchy- were absorbed into my brain as a 10-year-old. But this is the same perspective a social scientist might have on the world.

Dr. Adam H. Russell is head of Ground Truth, a research program run by DARPA - the Pentagon's research and defense division, responsible for the development of breakthrough technologies that have since become essential tools in our lives, from GPS to the Internet. With Ground Truth, researchers will use computer simulations to examine something even more complicated than the intricacies of the Mississippi: The causes of complex social behaviours.

How many individuals can cooperate in a group before the system breaks down? At what point do people start competing with one another? Could a simulation be used to test the effects of political decisions?

Or alternatively, "How can you anticipate the unintended consequences of an organizational structure?" Russell echoes back. The answers are complicated, but these are the kinds of questions that he and other social scientists hope simulations could bring insights to.

"For most of the things that National Security ultimately cares about, at some point there's social behaviour involved," Russell explains to me. The United States government has long solicited the help of the social sciences in studying complex social behaviour. And now ultimately the goal is to start using simulations to help find new ways of thinking about old questions about society. And while it sounds like science fiction, Russell believes that computer technology has advanced far enough to provide new ways of understanding prediction and probability.

"We use these models because our ability to think through the behaviour of complex systems, and the consequences of various assumptions about individual behaviour, is kind of limited," Russell explains. "And so these models can help us crank through what would actually happen given basic assumptions."

"If we can take a principled approach to using the simulations - building increasingly complex simulations - that might give us an idea when facing a problem in the real world. If we can assess the complexity of the problem based on things we learn in ground truth, we have a much better sense of the kind of approach we'll need to take to understand and potentially predict that complex social system."

So. "What would happen if we grew our own world?" asks Russell. At Ground Truth, simulations serve as test beds, artificial worlds that can be reverse-engineered by DARPA researchers who in turn work like detectives to unpack how and why a simulated agent acted the way it did. The conditions that kick those behaviours into action are known as the titular ground truth.

Then teams will test their methods of prediction. One group will build a social simulation based on rules known only to them. In turn, another team will be challenged to come up with an approach for discovering those rules.

Russell imagines one team announcing an impending shock to their simulation by, say, adding an influx of new agents into the world or removing a key resource. Then the opposing team will model the impact of this disruption, and compare their predictions with the true outcome, which DARPA and an independent evaluation team will score.

How accurate can a computer simulation of the real world really be? Russell is quick to point out the importance of healthy dose of scepticism when dealing in simulation. If a newspaper headline claims that scientists have discovered the origin of cooperation, the fine print probably says something different.

"I think if you actually talk to [these hypothetical researchers] they'll be the first to say, 'well we're not making that claim.'" Likewise, even if Ground Truth discovers a reliable method within a simulation, that doesn't mean it will work out in the real world.

So what can we understand about the world through computer simulation?

The episode of 99% Invisible ends with a eulogy of sorts for real-world models. The Mississippi River Basin Model was shut down in 1993. It was left derelict for a few years before becoming a local teenage haunt, and then a public park in later years.

At the episode's close, Stanford Gibson is interviewed - a numerical modeller and proponent of old-school physical models like River Basin. Gibson works on rivers systems, modelling sediment and working on river restoration projects. Is it true that once you learn the mysteries of the river the magic is lost? the host asks him. In other words, by understanding the mathematical equations that go into the nature of the river, does it stop feeling like a river?

No, answers Gibson. In fact, he says, sometimes at the start of a project, before he ever begins to model it himself, he will explore a river by kayak. Because "there are too many processes that you don't understand, that you can't represent in equations." The maths isn't enough to describe the real thing. And so the simulation isn't enough either.

A good rule of thumb comes from a remark by the statistician George Box. "All models are wrong," he says. "But some are useful."

Russell describes the goal of Ground Truth in similar terms. A simulation, he says, is to be "probabilistic rather than precise."

"But," he adds, "it should also give you greater confidence."

Header and cover illustrations by Anni Sayers.