Sinistar retrospective

Aaaargh.

Listen! Sinistar is talking to you from the ravaged wilds of gaming's distant past, and what it's saying is worth hearing. It's saying that games used to be so mysterious, so malevolent, so tantalisingly unknowable. It's also saying "I am Sinistar!" and "Beware, I live!" and "Aaaargh!" and then it's punching you in the nuts and stealing your wallet.

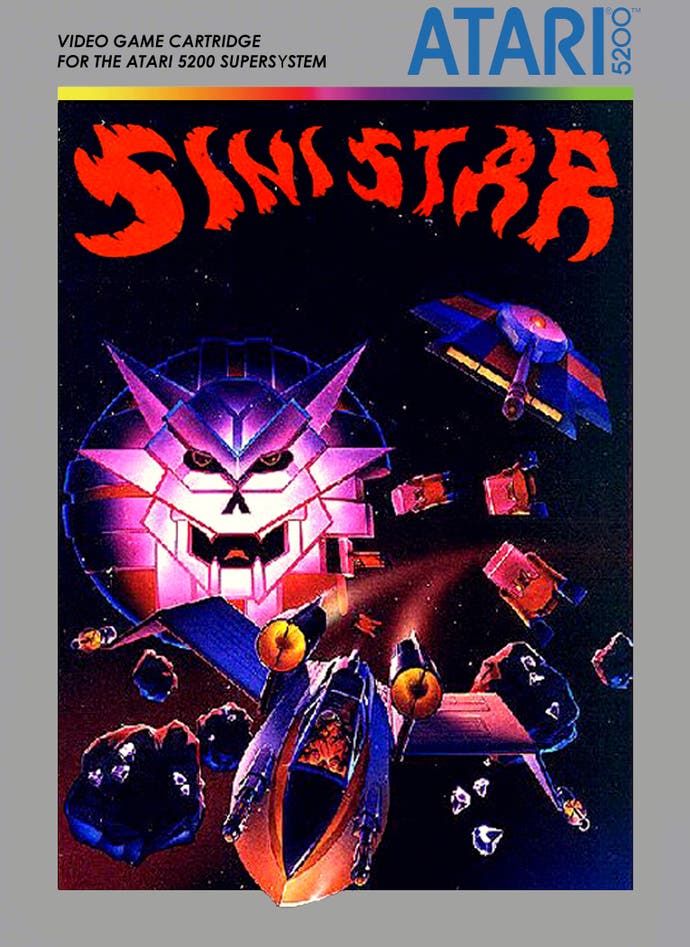

Sinistar is a wonderfully strange coin-op from the early 1980s. Sinistar is also a giant floating skull thing - a kind of outer space weapon of godly destruction that needs to be painstakingly pieced together from crystals that are found deep inside meteors before it becomes fully-operational. All the while, you're racing through the cosmos in search of those same crystals, too, so that you can manufacture Sinibombs - the only things that can bring Sinistar down (although maybe Cinnabons would work, too.) This would all be so easy if there weren't enemies swarming around the whole time, taking pot shots in your general direction and making life awkward.

That's about all there is to Sinistar on the surface: he's being built, you're trying to blow him up, and if you win, the whole thing repeats across a series of slightly different zones. The bare bones of the design don't account for that bizarre, luxuriously nasty atmosphere, however. They hint at what makes Sinistar a good coin-op game, but not necessarily what makes it one that's so very hard to forget.

Most of all, I suspect, Sinistar gets a lot of its strange appeal from the fact that it's an arcade game from the real early days that comes with a proper villain: a villain who's both horrible and intriguing and who sits at the very centre of the experience, impossible to ignore. Sinistar also takes a nod from other, older, media and builds up the antagonist - literally in this case - to create tension.

The relationship is complicated, actually. Sinistar's presence is felt everywhere, and yet both hero and villain lead separate lives for quite a lot of the game. He's off somewhere having the finishing touches added, and you're off somewhere else tracking down the ammo to do him in. This means that when you do actually cross paths, the moments have a real energy to them. Elegantly shaded graphics give this terrifying demonic skull the illusion of three dimensions, rendering him a more tangible threat than a billion wibbling Space Invaders, while his mocking voice has a peculiarly old-fashioned Americana twang to it - down to an emphatic performance from John Doremus which sounds like it was recorded at a rodeo circus theme restaurant somewhere around 1905.

Sinistar's famous for his talking, and that's not because talking arcade games are cool - although they most definitely are. It's down to the way he talks to you and the things he says. Sinistar only has a handful of phrases, but he uses them to taunt you and to threaten you. He really thinks you're a bit of a loser. Sure, the design team - including Amiga legend RJ Mical, Noah Falstein and Sam Dickers, who helped create video games' best ever audio effects back on Defender - thought he was saying Ron Howard rather than Run, Coward, but no matter: Sinistar's still a lot scarier, and more substantial, than most arcade game threats, while that lurking layer of abstraction - what the hell is a huge floating skull doing in space yelling about Happy Days anyway? - makes the whole thing troubling on a strangely primal level. When Sinistar told you to run - or even to ron - defeat seemed inevitable.

It was, most probably: Sinistar's a challenging game, befitting its glorious lineage. By 1982, Williams was gathering a sweet reputation as a company that released smartly-designed arcade machines that grabbed your money, threw you around a bit and then chucked you back out into the thick, boozy darkness wanting more. Sinistar, artificially made more difficult at the eleventh hour by greedy execs who worried players were living too long off a single payment, didn't buck the trend.

It punishes you, but it also gives you choices. You decide whether to attack Sinistar early on when he's being built, or stock up on bombs to get him later when he's more than ready to fight back, and while the mixture of attacking stuff and collecting other stuff calls to mind Robotron, the process of mining crystals from meteors and the elastic sense of physics suggests Asteroids might have been at the back of the design team's mind, too.

These are borrowings, perhaps, unwitting or otherwise, but Sinistar still had so many of its own ideas: the weird body horror of being eaten by a completed Sinistar, the panicked sense of having a mission to undertake in a large game space where your enemy was independently at work, too. This was singularly removed the straight-ahead up-and-at-'em agenda of so many other machines, and it was all enhanced by colourful graphics and a selection of lovely, understated sound-effects, from the mechanical purr as you spew Sinibombs into the void, to the polite clink as you bounce against an enemy or a rock.

Every day it seems that somebody with an ambitious project to pitch laments the fact that video games have long been preoccupied with mindless blasting. What Sinistar, and other early pioneers, can remind you, though, is that games about blowing things up often create an atmosphere that goes far beyond their most obvious mechanical elements. Williams' menacing classic was easily as interested in creation as it was destruction, for example, and it made the former aspect far more chilling than the latter. Don't underestimate Sinistar, in other words. Just listen to him. Beware. I live.