Skullgirls Review

Death becomes her.

Skullgirls will enjoy little of the warm-hearted generosity that normally accompanies the release of a micro-team's indie game. While this 2D fighter's underdog credentials are impeccable - designer Mike Zaimont worked for blockbuster studio Pandemic before it folded and he struck out on his own to work on this passion project - the fighting game community has little room for sentimentality.

Rather, Skullgirls lives or dies on the quality of its balance, the 10,000 micro-decisions that combine to decide whether a fighting game has a fighting chance in one of the most brutal and unforgiving genres. The fact that this is a £10 game is largely irrelevant. The cent-per-hour cost of a perennial fighting game drops to insignificant levels if it is appropriated by the tournament community; Skullgirls must go toe-to-toe with Street Fighter 4 and all the other heavyweights and come out standing to earn its applause.

The game has a better chance than most. Zaimont is a tournament-level fighting game competitor (a champion on the EVO circuit) who helped balance Japanese fighters BlazBlue: Continuum Shift and Marvel vs. Capcom 2. His understanding of hit-boxes and combo strings is not only quietly evident in the game's systems, but also explicit in what is one of the most useful and comprehensive training modes seen in any fighting game to date.

The presentation may be protracted, with long, laboured intro animations, but the content is precious, leading the player through the basics of punching, kicking, blocking and jumping to far more advanced techniques that explain in clear detail what must be mastered to progress. Here you'll learn when to block high and when to block low. You'll learn about overheads, cross-ups, mix-ups and when to extend a combo and when to cut it short through hit confirmation. The lessons apply to almost all modern fighting games and so, arguably, are worth the price of entry on their own.

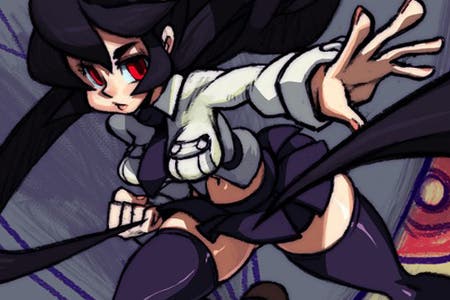

Skullgirls itself, though, is likely to be somewhat divisive, albeit from an aesthetic standpoint rather than a systemic one. The all-female cast has been overtly sexualised, but to single Skullgirls out as a worse offender than the 16-bit games and art styles it pastiches would be ungenerous.

Indeed, artist Alex Ahad draws influence from Tex Avery's slapstick visual humour just as much as Super Smash Bros.' panty-flash shots or Dead or Alive's bouncing breasts. This hybrid influence certainly infuses the game with a unique art style. While the choice of 1940s Americana, whisky jazz and darkened saloons is a pleasing departure from the usual braggadocio storylines of the fighting game clique, it fails at times in the execution, which is undistinguished and workmanlike.

In-game, however, animations flow together with style, jostled along by a string of systems that are wonderfully balanced and proportioned. Skullgirls borrows some of the structure of Marvel vs. Capcom 3 but slows down that game's manic pacing while reining in the exuberant specials to something more readable.

In a similar way to Capcom vs. SNK, players pick teams of one, two, or three characters, different combinations offering different strategic benefits and drawbacks. Single-character choices are incredibly strong with high health, whereas if you choose a team comprised of three characters, each will be relatively weak. The rarely-copied system worked very well in Capcom vs. SNK and is equally effective here, although the limited character roster (just 8 for launch) does restrict your options.

The characters that are here, however, are interesting, diverse and at times even revolutionary. Ms. Fortune, for example, is a fast-paced rushdown character who can detach her head and have it attack independently of her body. Meanwhile, Cerebella compensates for her size, bulk and close-quarters grappling focus with a nimble double jump.

The promise of new characters and content implies that Skullgirls is to become an ongoing, supported service of a game, but it's difficult to shake the feeling that, despite the robust core, this is a game rushed out for release. In particular, the lack of any character-specific move list within the game (you can find this information online, but not in any menu) is a huge oversight and, for many who lack the time or energy to trial-and-error their way towards a full vocabulary in the training mode, will obscure too many of the game's secrets to warrant investment. This sense of a not-quite-baked game is exacerbated in a training mode that lacks many basic options (such as input display or the ability to set the dummy character to 'crouch', or 'jump').

Online, the game makes use of the fan-made GGPO netcode (previously used for Street Fighter: Third Strike and, most recently, Street Fighter x Tekken) which prizes the purity of the inputs over the purity of the animation frames in the face of lag. Skullgirls even offers configuration suggestions on a per-opponent basis for the match based on latency, a great feature for ensuring that online fights are as fair and balanced as possible considering the locations of both participants. Even here, however, there's a lack of features, from spectator modes to replays to endless lobbies - all options that players have come to expect regardless of a game's price point.

Despite these reservations, Skullgirls is a welcome addition to the genre's bustling roster. While Street Fighter 4 has acted as the catalyst of a fighting game revival, for the most part Japan has led that charge, with few Western studios chancing their hand at the genre and next to none of their games featuring on the tournament circuit. So an American-made game that not only understands the fundamentals but is able to build upon them in interesting ways is a welcome sight, even when the execution around the core is lacking.