Sleep Is Death was ahead of its time

Tale of tales.

Friends have been gathering around tables to play pen-and-paper games together for decades, but what's changed recently is that now those friends can have an audience while they do it. Whether through 'actual-play' podcasts, Twitch livestreams, or sold-out performances at gaming events, there is a new audience eager to spectate while creative people improvise stories together.

I understand these audiences mainly because, back in 2010, I spent hours trawling a website called SIDTube. SID stands for Sleep Is Death, the name of Jason Rohrer's 2010 two-player storytelling game in which one person controls a single character and the other weaves the story around them as game master. At the end of each story, the game would output the actions of actor and storyteller as a flipbook of images that users could then upload to SIDTube and sites like it.

Sleep Is Death's popularity was short-lived and SIDTube slipped offline years ago, but while reminiscing with a friend recently I discovered that someone has uploaded the site's archives to ModDB. There are 500 stories available and in among them are a handful in which I am either the actor or the storyteller.

This is how I came to realise two things. The first is that Sleep Is Death was ahead of its time. The second is that I'm a terrible person.

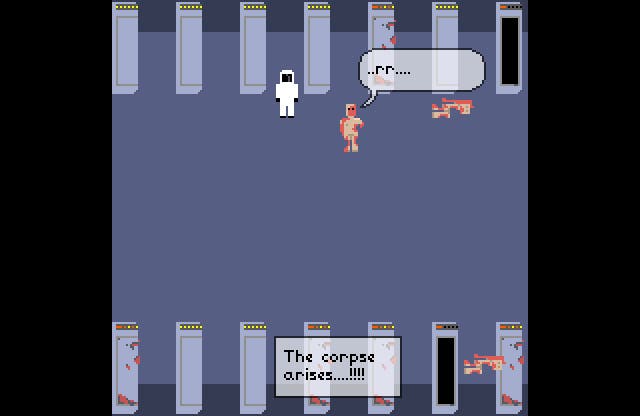

Play in Sleep Is Death advanced by turns: the actor would type dialogue or an action they wished to perform, and the storyteller would then have a time limit in which to make the world respond. This was normally panic-inducing for the storyteller, who had to scramble to use the game's simple editing tools in order to draw sprites and scenery, write dialogue, and even adjust a chiptune soundtrack via a sequencer. You could use all these tools beforehand to craft the elements you thought you'd need in your story. In reality, most people stuck to the stock assets that came with the game, but the time pressures during play still encouraged fleet-footed creativity and, importantly, pushed both players into making mistakes. Mistakes are a gold mine of comedy in improvised storytelling, it turns out.

What was most interesting about a site like SIDTube was being able to see other players go through the same scenario with the same storyteller as you but make a completely different story. Think of it like a more detailed and interesting version of the stats screen at the end of a Telltale game, letting you know how other players made each available decision.

I re-lived this experience after downloading the SIDTube archives. It took a while to find the story I was looking for, but I recognised it immediately when I saw its first image. Story 282 begins in a single, tiny room, in which two characters are sat on a bed. "Hey, this isn't so bad. I reckon you've got another foot on the last place," says one, controlled by the storyteller.

As I flipped through the images, at first I couldn't remember if I was the player in this version of the story. After some conversation, we discover that the characters live in a future struggling to cope with overpopulation. This tiny room is as large as anyone is allowed. It's grim - until the characters smash through one of the walls to discover a second, empty room. This new room is relatively huge, has windows, and has seemingly been forgotten about.

I realised it definitely wasn't my playthrough when the player, looking upon this newfound bounty, said, "If we're going to use this space, we need to do something good with it." Over the course of the rest of the story, the player fills the new room with beds and sets it up as a shelter for homeless friends, relatives and strangers.

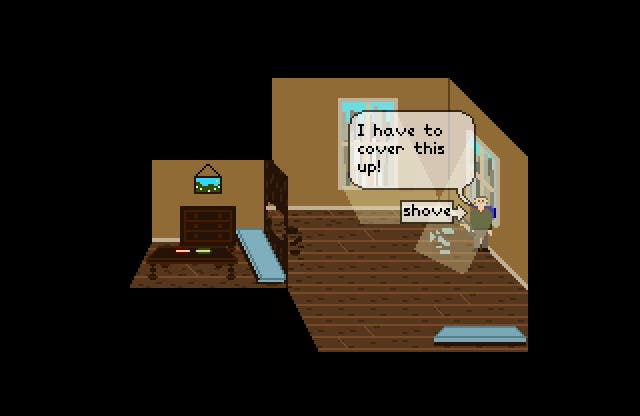

It was a few minutes later when I found my version of the story in the archive, numbered 331. I skipped to near the end of the images to check how it played out and it was as I remembered it. The enormous and hidden room is as empty as when we find it, bar some broken glass on the floor. I'm pushing the storyteller - in the fiction, my friend - out the window and to his death in order to keep the room all to myself. I am a terrible person.

I once read in an article that the most basic rule as an improv performer is to always accept the premise posed by your fellow actors. If someone says the telephone is ringing, you answer it. If you disagree that the telephone is ringing, or even that there's a telephone, the scene is dead.

This leads to my only defence. In this telling of the story, the storyteller's first line of dialogue was different. "You're an arsehole. How the hell did you luck out and get all this space?" I was just accepting the premise that I am an arsehole.

There was another twist in the tale, too. When the storyteller and I first break through the dividing wall to discover the hidden room, there's the body of a man inside. We initially assume that he's dead but he turns out to be alive. I discover this while throwing him out the window, also, while my friend is out of the room. I am a terrible arsehole.

Note that when the friend returns, I lie to his face. I tell him the man woke up and lunged at me, we tussled, and then he willingly dove through the window. To be clear, while friend-the-character was out of the room, the storyteller could see everything I did. I love the dynamic of this: a lie is being told, both players know it, and both players go along with it until the drama demands otherwise.

I feel like these stories are a strong example as to why Sleep Is Death has so much potential. It's not just that this simple premise spun towards such entertainingly different endpoints across different playthroughs. It's that they were still so fun to read so many years later. From the amount of time I've spent poking around the archive, I think that holds true of even the stories I didn't personally play.

Anyone who has ever taken on the role of game master for a D&D or other pen-and-paper group knows how much work it is. For all that you intend to improvise during the game itself, you still need to spend time beforehand conceiving of characters and locations and planning combat encounters. That was no different in Sleep Is Death. Finding a good storyteller who had put effort into crafting a real story was rare, and the rewards for those storytellers were slim.

That might be different today, when Sleep Is Death stories could be experienced as more than static images after the fact. If Jason Rohrer were to make Sleep Is Death 2: Sleep Deeper, the game could make use of all the leaps in technology that have happened since. Stories could be livestreamed by the players telling them, and sometimes perhaps a Twitch audience could collaborate as the actor by voting what to do next. The flipbooks could be rendered as GIFs and shared via social media rather than on out-of-the-way community fan sites. Good storytellers could use it as the accessible tool it always was, but now with an audience ready to listen.