Someone should make a game about: Doo-wop

Shoo-doop, shoo-be-woo.

For the first dance at our wedding, my wife and I chose The Danleers' one and only hit, One Summer Night. It's not a very famous song, and although we had listened to it a lot together - along with many other classics from this magical moment in American pop - it didn't hold a particularly special meaning for us. The lyric is on point for a July wedding, sure, not to mention reminiscent of the heady days of late May and early June a couple of years earlier, when we had first dated as the heat started to rise off the London pavement and the city went happy-mad under an opening sky. But that's not why we picked it either.

We picked One Summer Night because it's doo-wop, and there is no more romantic sound on earth. If you want to make someone feel an almost painful nostalgic yearning; if you want to transport them to a world of elegant courtship and sublimated sexual heat; if you want their hearts to soar and break, and you want to do it all in under two-and-a-half minutes, then you can't do better than doo-wop.

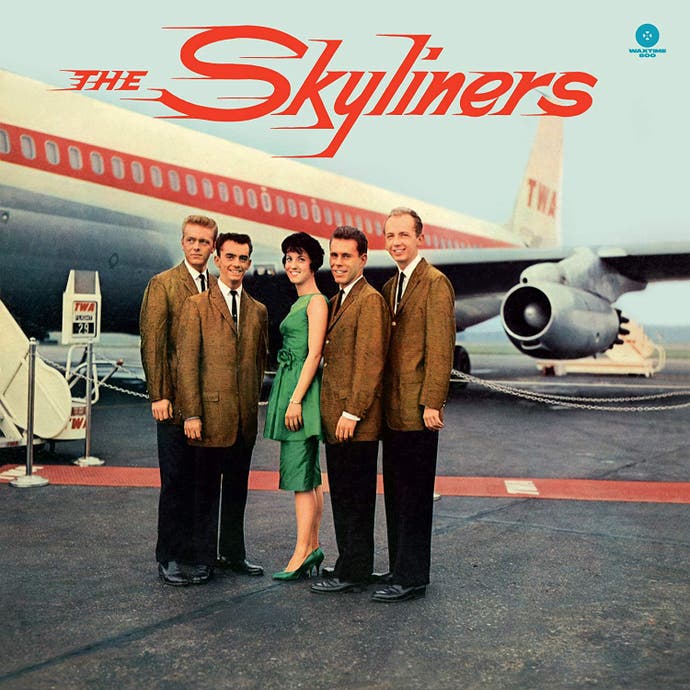

Here's your potted wiki: doo-wop is a genre of rhythm and blues and a close cousin of rock'n'roll that was popular through the 50s and early 60s. It's defined by harmony singing, often contrasting a high tenor voice with a deep, deep bass, and was usually performed by penguin-suited vocal groups with names that instantly conjure a world of neon-lit diners and chrome-edged tailfins: The Drifters, The Skyliners, The Five Satins. Its roots go back to southern gospel but also to New York's pop production lines of the early 20th century, Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, and it has strong precedents in 30s and 40s vocal groups like The Ink Spots. Like hip-hop later, doo-wop was originated as an a capella street music by black teenagers who couldn't afford musical instruments, though it was quickly seized upon by Italian-Americans as well. The name doo-wop refers to the nonsense sounds often sung by the backing singers as a rhythmic bed for the lead's soaring melody.

It is majestic stuff. (I've put together a short playlist of some of my favourites on Spotify.) It's one of the purest expressions of that very American kind of artform, where artless simplicity, sentimentality and the efficient commercialisation of folk art somehow combine to make something universal and transcendentally beautiful. Doo-wop has strict rules. The songs are always and only about teenage love and sex. The lyrics have a stunning straightforwardness: "One summer night / We fell in love / One summer night / I held you tight / You and I / Under the moon of love." There will be a bridge, sometimes done in a hilariously earnest spoken-word style. The arrangements are luxurious and complex, but the melodies are simple and the runtimes are ruthlessly short.

One reason doo-wop sounds so romantic today is that it has been so romanticised itself. In particular, the New Hollywood movie directors who grew up with this music - Spielberg, Lucas, Scorsese - made it an integral part of their mythologising of 50s American pop culture in films like American Graffiti, GoodFellas and Back to the Future. The imagery they created and scored with doo-wop classics has since become a global shorthand for the good old days. At the same time, David Lynch subverted this nostalgic imagery in Blue Velvet, as he cut from white picket fences and smiling firemen to writhing bugs under the strains of Bobby Vinton's song, taking us to suburban America's dark underbelly. This ironic contrast worked so hauntingly well that it became a meme in its own right and was much copied - including by Black Isle, when it used the innocuous strains of The Ink Spots to introduce us to Fallout's nuclear wasteland.

Doo-wop is both formal and unbridled, graceful and profane. It has a courtly discipline, an almost chamber-music-like strictness of form, yet it roils with raw, adolescent emotion. It can be nonsensical (The Chips' Rubber Biscuit), plain dirty (Sixty Minute Man by The Dominoes) or wryly philosophical (The Drifters' exquisite Fools Fall in Love). Its most stately classics - I'd pick out Since I Don't Have You by The Skyliners, Tears On My Pillow by Little Anthony and The Flamingos' unforgettably eerie I Only Have Eyes For You - have a tragic intensity that is almost operatic. When I listen to doo-wop, I fully know what the poet Philip Larkin meant when he talked about "the strength and pain of being young".

I don't necessarily mean that someone should make a game about doo-wop, but I would like to see more of doo-wop's spirit in video games. More plain-speaking, unbridled romance; more heartbreak, worn lightly but felt deeply; more teen longing; more sex, but also more courtship. What I hear from video games - literally and metaphorically - is a lot of orchestral symphony, crunching rock riffs and wailing solos, thoughtful folk and shimmering synth pop. And I love all those things. But just once I would like a game to approach me with the smooth, measured yet impassioned pace of doo-wop, take me in its velvet-clad arms, woo me in two minutes, and leave me wanting more.