Someone should make a game about: Misperception

Acting the goat?

Hello, and welcome to our new series which picks out interesting things that we'd love someone to make a game about.

This isn't a chance for us to pretend we're game designers, more an opportunity to celebrate the range of subjects games can tackle and the sorts of things that seem filled with glorious gamey promise.

Check out our 'Someone should make a game about' archive for all our pieces so far.

I left the office one night last week and saw a woman holding a shark walking towards me. If this had been Hove, I might have been surprised, but since it's Brighton I went along with it. (In Hove people walk their sharks on leads.) When I looked again, though, she wasn't holding a shark at all. She was holding a large sheet of blue card, bent over on itself with its cream reverse peeking out at the bottom.

The upshot is I probably need new glasses. But in truth this stuff happens all the time anyway. My eyes aren't brilliant, which means when I walk around my brain often makes guesses at stuff. Over the last few months I've started to lose my hearing a little, so now my brain makes guesses when people talk to me too. This is maddening for everyone else, but I'm always fascinated by the creativity of what the human brain comes up with - and the certainty I feel that my reading of a situation has been correct even when it hasn't. It's made me think a bit about this whole business of perceptions and misperceptions. It's made me value misperceptions a little more than I used to.

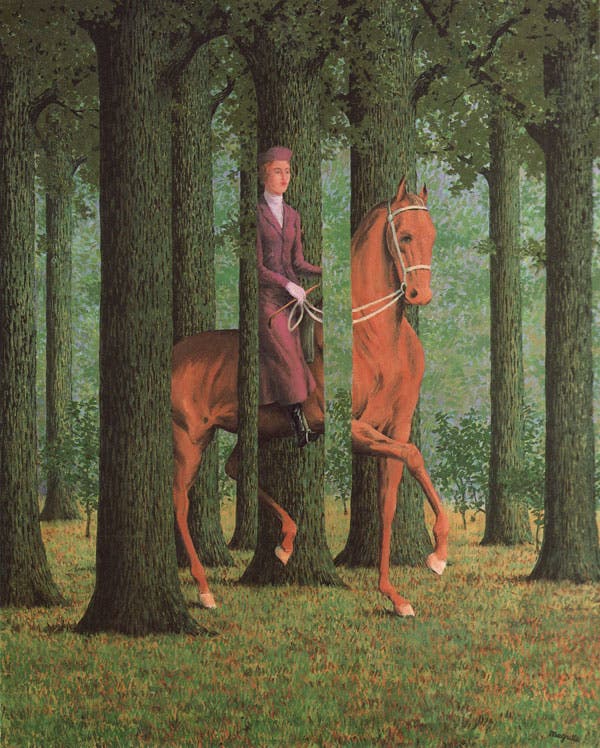

Not that misperceptions have been ignored until now. Arguably the greatest work of literature, Don Quixote, is all about misperceptions. Driven to fancy by his heroic reading, Quixote's adventures consist of a sequence of things inadequately perceived - and as a result his world becomes richer and the world of his acquaintances does too. One of my favourite children's books, meanwhile, is Spectacles by the great Ellen Raskin. "My name is Iris Fogel and I didn't always wear glasses," it begins. Pretty soon a fire-breathing dragon is knocking at the door, only to be revealed as Great-aunt Fanny. A chestnut mare in the parlour is really a baby-sitter. You move through the book seeing what Iris sees - what she misperceives - and then you turn the page and see the reality.

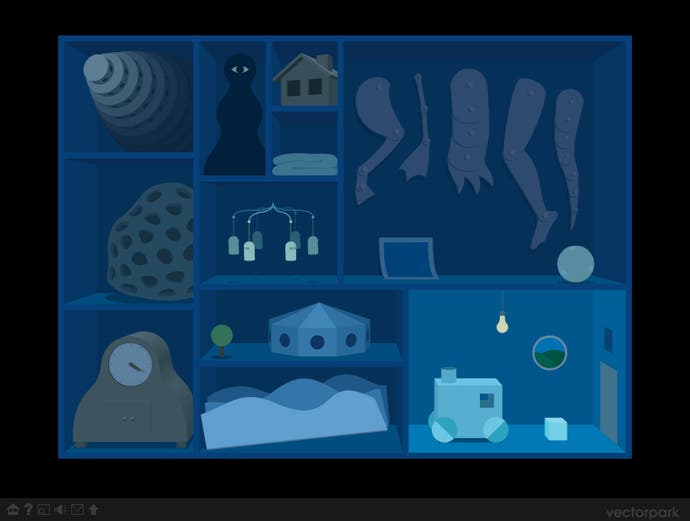

If this sounds a little game-like already - I would love to see Vectorpark let loose on misperceptions or the works of Ellen Raskin or both - then how about James Thurber's old New Yorker piece The Admiral on the Wheel. One of Thurber's eyes was injured when he was a child, and as his sight deteriorated throughout his life he got a lot of value from the world as only he saw it. In this particular piece he talks about his experiences following the breakage of his glasses. "For the hawk-eyed person life has none of those soft edges which for me blur into fantasy," he writes. "For such a person an electric welder is merely a welder, not a radiant fool letting off a sky-rocket by day."

"The kingdom of the partly blind is a little like Oz," he continues. And then he offers examples. He sees a "noble, silent dog" lying on a ledge above the entrance to a brownstone on Fifth Avenue. He sees a flock of white chickens in the garden. He sees a little old admiral in full dress uniform riding a bicycle. A Cuban flag flies over a national bank.

I figure it would be wrong to end a piece on misperceptions without turning to the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks. Like a lot of readers I fell in love with him over the short course of The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, a study of a man with such profound visual agnosia that he tries to pick up his wife's head at the end of a consultation and put it on his own. Back in 2015, Sacks started to experience problems with his hearing, which led him to record his experiences in a little red notebook labeled "PARACUSES". God I love Sacks: "I enter what I hear (in red) on one page, what was actually said (in green) on the opposite page, and (in purple) people's reactions to my mishearings, and the often far-fetched hypotheses I may entertain in an attempt to make sense of what is often essentially nonsensical."

In a single column, Sacks gets at a lot of the power of misperception: he remarks on how extraordinary it is that mishearings "always present themselves as clearly articulated words or phrases, not as jumbles of sound." And while they are not hallucinations, like hallucinations "they utilize the usual pathways of perception and pose as reality - it does not occur to one to question them."

For Sacks, mishearings prey upon the fact that "speech is open, inventive, improvised; it is rich in ambiguity and meaning." This vulnerability of speech is, of course, also its great power. Maybe misperceptions are a price we pay for our richness of experience.

And they have richness themselves. Sacks suggests there is "often a sort of style or wit - a "dash" - in these instantaneous inventions." Instantaneous inventions! If that isn't filled with gamey promise, I don't know what is.