Someone should make a game about: The collective unconscious

While we're Jung.

Hello, and welcome to our new series which picks out interesting things that we'd love someone to make a game about.

This isn't a chance for us to pretend we're game designers, more an opportunity to celebrate the range of subjects games can tackle and the sorts of things that seem filled with glorious gamey promise.

Check out our 'Someone should make a game about' archive for all our pieces so far.

Do you ever wonder how people and animals sometimes just... know things? For example, a baby will automatically hold its breath when submerged in water - but please don't try this at home with your own baby (certainly don't try it with somebody else's either). And generally speaking, we all share the same sense of right and wrong, don't we? Where does that come from?

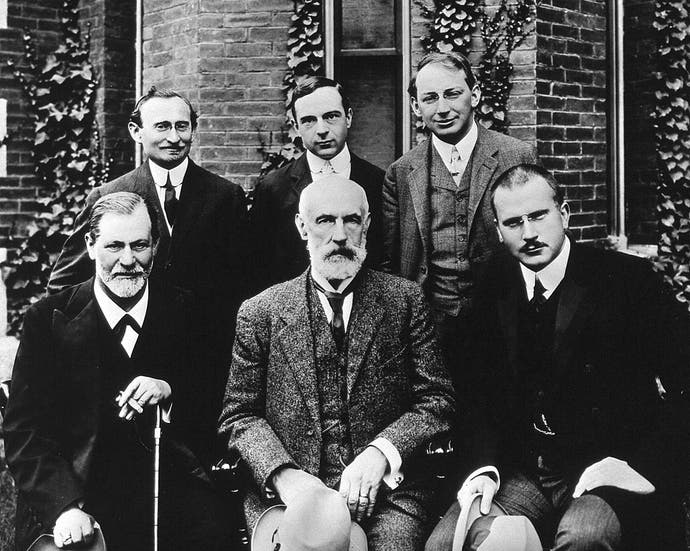

According to psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Carl Jung, this and much, much more comes from something which he called the collective unconscious. Now, it would be wrong to ignore the fact that Jung's legacy is haunted by the vile spectre of Nazi sympathies. At the very least, it is true that some of his writing was enthusiastically devoured and distributed by Nazis, and finding examples of why isn't too difficult. This theory, however, has become sufficiently detached from Jung himself, to the extent that it remains to this day easily discussed and debated without needing to delve into the darker corners of its author's history.

To return to the theory, the collective unconscious was something that Jung thrust into the heart of his psychiatric work. He claimed not only that it is the source of our sense of right and wrong, but that it is the source of archetypes; essentially images and ideas fundamental to belief and life in general. All archetypes, he believed, morphed into different interpretations across time and geography - but the mother is the most influential of all. In addition to a literal mother, this was proposed as the source of belief in and devotion to things such as one's country or religion as a maternal figure. It is for example an explanation for why various religions, independently developed across the world, share many events and basic beliefs - they are, at least in part, a manifestation of the collective unconscious. No matter where in the world you are, your beliefs and behaviour are (according to Jung anyway) driven by these inherited memories that stem from the same ancient time.

Archetypes played a big part in Jung's interpretation of dreams. Images and events in dreams are usually described as metaphors which, for Jung, could always be traced back to an archetype. One way or another, he would link any dream event with an archetype, such as birth, death, or the hero. Nonetheless, he believed that dreams could not be well interpreted without an understanding of the individual dreamer, which is something of a contradiction. The collective unconscious does not allow an awful lot of wiggle room for free will.

When it comes to nature vs nurture, the collective unconscious falls on the side of nature with a heavy thud, which is in part why it's never been universally accepted. It's also been pointed out that this is not a scientific, verifiable theory - it's impossible to either prove or disprove. Straddling as it does the worlds of philosophy and psychiatry, the theory is considered both by people who demand empirical evidence, and those who consider it unnecessary. It was never going to sit well with everybody.

Think of the collective unconscious not as a manual to understand how a car works, but a detailed map of the one small town this car is allowed to explore. If we can only ever think and act according to a set of rules we cannot consciously access, then sure, much of the world becomes easier to understand. But we must sacrifice our individuality at this altar of knowledge. If the most fundamental elements of thought are already there for us from birth - basic images and what they mean, what is right and what is wrong, what to fear and what to desire - then how much of what we choose to do is actually our choice? How much can we say we have learned from friends and family, and how much is simply programmed into every person on the planet? Perhaps a game could tell us.