Sometimes it's the context beyond the screen that makes a game great

Or why games are secretly like restaurants.

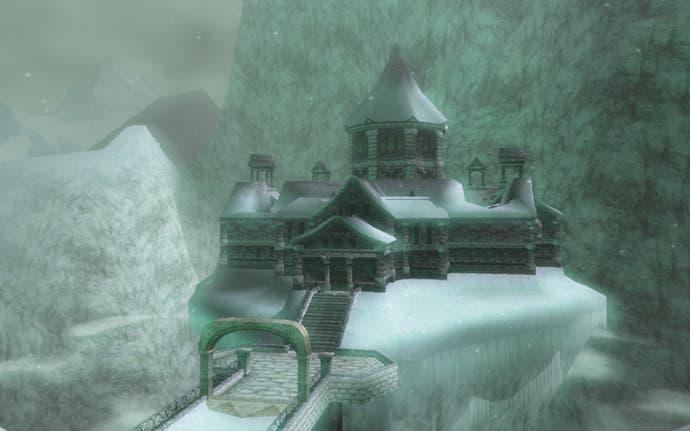

There's a wonderful dungeon in Twilight Princess which is nothing like a dungeon really. It's like staying at someone's house - an old and very comfortable house, up high in the mountains, nestled in the snow. My memory of this place is quite vague by this point. I think it might have been where I picked up the ball and chain, and I don't recall it being unnaturally devious or punishing as Zelda dungeons go. What I really remember, though, is that there were friendly, people-ish things bustling about as I explored, and there was soup on the boil.

I'm mentioning this because it's my friend Stu's favourite Zelda dungeon. And it's his favourite for quite an interesting reason. It's his favourite because purely by chance he first entered this cosy winter getaway on Christmas Eve one year. He played the game amongst Christmas lights and brown paper packages and mulled wine and all that jazz, and everything melted together in his mind.

I played that dungeon in Nintendo's old UK HQ, locked in, it felt, over a long weekend, rattling through a massive, massive game as quickly as I could for a review. I thought the dungeon was clever and charming, but these are distant words. I had to hear about Stu's experience to truly see it for what it was. And looking back it has made me think about the things that make great games truly great. There's the design, obviously. There's an idea so good, sometimes, that even bad design can't ruin it. But there's also the world outside the screen. This is much more unpredictable. But occasionally it works a kind of magic.

To attack it from a different angle, I've been reading a lot of food writing recently, and I've become mildly disappointed that games aren't more like restaurants. Great food writing often has a bit of a journey to it. There's expectation, the arrival, the reality of the restaurant, and then the food and the eating, and all of these things sort of melt together. Jonathan Gold, who died recently and left some astonishingly great food writing behind him, is the master of all this stuff. He wrote about food as a way of writing at the same time about communities and cultures and history and traditions and people. His writing is delicious in that way the best food writing is, but it's also filled with things that matter as much as the food, or that enhance it in context.

So I've been thinking about all of this and being sad, in a way, that games are so available. This is a ridiculous thing to be sad about, I know, but I have had this fantasy of a game that you have to travel to, just like you once had to travel to arcades. The journey takes a while. The place the game is located in is interesting and atmospheric. There's a bit of a story to things, and as you play there's stuff continuing to go on around you - life, with all its sounds and images and smells and all that jazz.

What I've realised, finally, is that games have all this stuff anyway. It's just far more haphazard. I could tell you about how great the first Monkey Island game is, for example, but what I'd really have to tell you about to make it sing for me is how I played it for the first time staying over at a friend's house, staying up all night, Melee Island's midnight blues and blacks on the screen and the sodium light from the street lamps outside. Without all that, the game is great, but it isn't quite as great. It has lost something vital, and I have never been able to recapture it.

I have dozens of memories like these, but I have to tune into them. Or rather I have to remember not to tune them out. Mario and Luigi: Superstar Saga is quite a game, but I remember it most fondly when I think of playing it one Christmas - often Christmas it seems in these memories - with Moloko on the TV on Jools Holland, Roisin Murphy crawling inside a bit of amplifier kit or whatever and getting stuck. I remember playing Advance Wars for the first time on the slopes of a university library, with the perfect sun to bring the GBA screen to life. I have hundreds of memories like this.

So that's the trade off, I guess. Games can't control the context in the same way that a restaurant can try to. But they become perfect vehicles for involuntary memory. You load them up and, if you're tuned in right, the memory of the last time you played, or the best time you played, will be in there waiting for you on the start screen.