Space Harrier retrospective

You're doing great!

In the 1980s games were not everywhere. It is almost impossible to explain arcades, in the world of App Stores and Steam, without knowing that. Arcades were not only beyond home consoles, but they were bright smoky heavens - the places with the biggest, best and loudest games. Even in this jungle, some beasts were alphas. The special ones. The premium Space Harrier cabinet was a cockpit, complete with flightstick and surround sound. This thing was massive and it moved . A lanky kid would get in and puts 20p in the slot. "Welcome to the Fantasy Zone!" The speakers behind your head kicked in. "Get Ready!"

Not all Space Harrier cabinets were equal. As well as the moving version there was a fixed alternative, and a simple stand-up cab with joystick. Yu Suzuki, Sega's hitmaker and the king of the arcades, was a special kind of designer: he had to not only design a game, but do it alongside the development of the cutting-edge tech it would run on, and then at the end give the whole production physical form. Though arcades still struggle on, this was always a doomed artform.

I mention all of this because Space Harrier is a classic, and that designation always rather obscures why a game's design is worth looking at in the first place - as if the greats arrive fully-formed. Out Run, another Suzuki masterpiece, especially suffers from this. Before Space Harrier Suzuki and his team had just scored their first hit with Hang-On, pioneering Sega's new pseudo-3D sprite-scaling tech. Space Harrier, released only three months later in October 1985, goes from the tarmac to the stars: propelling the player forwards faster, bombarding them with enemies, and abandoning reality's bonds entirely.

The speed at which Space Harrier moves has rarely been matched. It's not an easy thing to design a game around. Many other games have fast parts, or certain mechanics tied to speed - and it's interesting to note how many take control away at this point. Space Harrier only has one gear, and it is fast as hell. Most games I have an accurate memory of. Every time I play Space Harrier, and it's a personal favourite, the speed blows me away one more time. It is a monster.

The hair-whitening pace only works because of the controls - and though a pad's fine, the extra bit of magic was in the arcade cabinet's flightstick. This means pulling back sends Harrier up and forwards is down, a configuration perfectly suited to on-rails movement requiring split-second adjustments.

Space Harrier is a shooter, of course, but the only skill that really matters is dodging. An onrushing stream of enemies, glowing bullets and obstacles home in on the Harrier's position and the key tactic is simply to keep moving. The pros pull lazy eights across the screen, somehow lining up shots simultaneously, but I tend to stick with a simpler loop, which regularly descends into scribbles.

The flightstick, even when you're not using one, is also responsible for a delicious kink in the controls - the Harrier pulls back to a central position when you're not moving him. This acts as an essential fulcrum to what is basically tunnel-dodging, and factors into how you move all the time; the slow reset of position becomes a piece of momentum used between wild dashes, a slight adjustment already accounted for in the next swing.

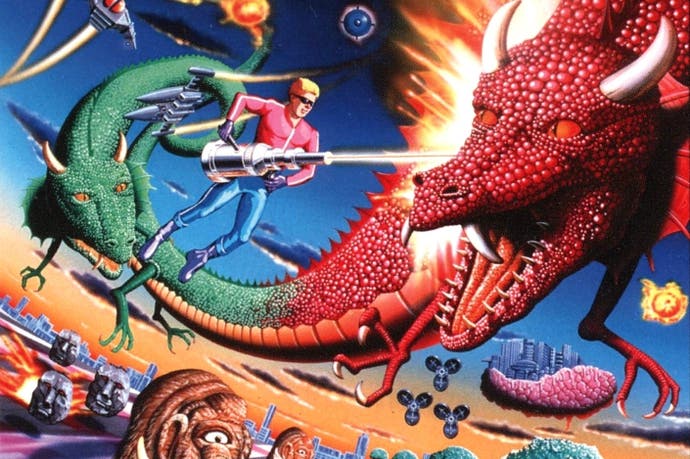

Breathtaking enough - but great systems don't always get the cash. The other side of Suzuki's genius for arcade games was, for want of a better word, their flashiness, balanced between cool and OTT at all times. The Space Harrier is a guy with a blonde mop, the reddest red jacket, and blue jeans. He looks awesome, and he flies. Each of the eighteen levels has its own style and colour scheme, but from the third world Amar is where things begin to take off. This sudden swing into psychedelia leaves no illusions about its influences: the obstacles are massive, violently-hued mushrooms. Undulating laser blasts float forwards as the scarlet sights of robots track you, and single-eyed mammoths wonder what's flashing past.

The next level immediately adds another trick - boxing you in with a ceiling. As it slams down the obstacles become supporting columns, in deadly configurations that need threading through. These quick switches between the patterns and shapes of enemies are devastating to those slow of reaction, and the sheer thrill factor of Space Harrier comes with that arcade caveat; this is a hard, hard game. Before getting it on Virtual Console I'd never even seen the halfway point.

Yet Space Harrier pulls you back, and today still plays beautifully - even when spamming infinite credits. You want to see all the bosses, these crazy Chinese-style dragons and giant heads, the alien octopii, psychedelic flies, jet-helicopters, and random bits of geometry. There came a point in Space Harrier's design, one must conjecture, when the question of how far they'd push the mental stuff came up. It's a Yu Suzuki game. They went all the way.

The final word is for the title screen on that monster of a cabinet; crucial to an arcade game in a way home software could never understand. Space Harrier had the works. Little animations show the robot's gun barrel gleaming, the mammoth's eye looking both left and right, before brief cutaways into attract mode. The genius touch though, the special one, is simply that the Harrier is smiling and waving at you. A human face in the phantasmagoria, an invitation always waiting. A welcome to the fantasy zone.

Get Ready!