Spaceplan is the 2001 of clicker games

"I hope this doesn't get too tedious."

It is the fate of the clicker game to start very small and end very big. Often, to end very, very big.

By 'small', I mean maybe you make a cookie. Maybe you make another, then another, then another. By 'big', I mean maybe you own cookie factories, a cookie empire, a planet of cookies, a religion based around the consumption and production of cookies.

One more clarification. By 'end' with regards to a clicker game, I mean, be abandoned. You click and you click for weeks and maybe months. Then one day, you suddenly realise you can click no more. You have no more clicks to give. And so you slouch away, disgusted - disgusted with clicking, with yourself. The clicker game has foreseen all of this, of course. Because, for some strange reason, it is the fate of the clicker game to be self-aware, to understand the dark compulsions that drive its array of daft systems, and to understand that these compulsions only lead to one destination.

I have been playing a clicker game for the best part of this week. It's called Spaceplan, and it's elegant, witty, and nice to look at. It's satisfying stuff, with a lovely sense of personality, and yet, whenever Chris Bratt looks around from his computer and sees the numbers ticking up on my monitor, hears the mouse click-click-clicking away beneath my right hand, his eyes grow narrow and he says, "Come on, pal. You're better than this."

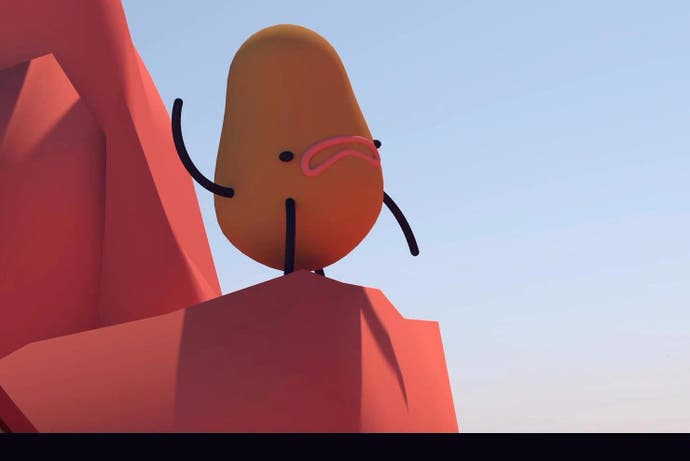

I'm not sure I am, to be honest. Spaceplan is surprisingly wonderful, a clicker built around exploration, the cosmos, black holes and big bangs and the delights of the humble potato. It is Kubrick with a spicy paprika coating. It is Interstellar with fries. Furthermore, it has two features I wasn't expecting to be quite so prominent: a coherent story, and an ending. Do other clickers have that last element in particular? I don't know. I've always abandoned them. But with Spaceplan, just knowing the ending is there has made me stick with it.

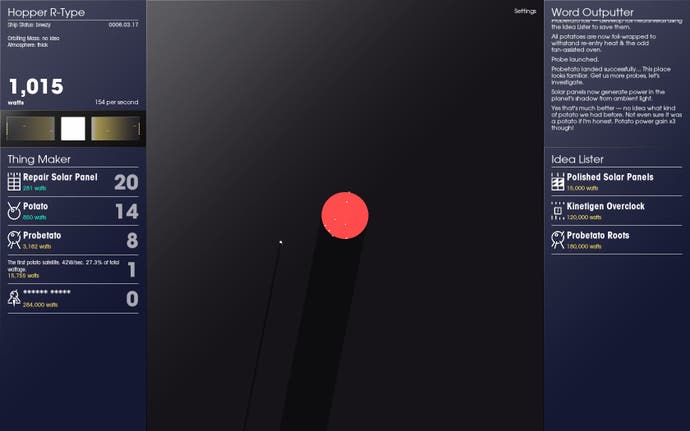

Let's save the ending for later. For now all you need to know about Spaceplan is that, for your first dozen hours or so, it's as standard a clicker as you could expect. You are orbiting a planet. You are clicking to bring systems online. You are clicking to launch potatoes towards the planet. You are clicking to make sure the potatoes survive the journey. You are clicking to plant towers, to make your clicks more effective, to make sure that you start to earn the in-game currency - watts, but there is a scientifically accurate mode to toggle between that replaces watts with joules - without clicking at all.

And all the while, as new things to make appear in the Thing Maker column on the left of the screen, as new ideas are listed in the Idea Lister column on the right, you discover that you are bring drawn into something, a narrative with an intriguing hook, words output one after the other in the Word Outputter on the top right. This planet you're orbiting, this planet you're bombarding with spuds: why is it so lifeless? What is its history? Things are already turning, aren't they? Things are transitioning from small - one potato, two potato - to very, very big. And when a game knows about Stephen Hawking and the birth and death of the universe, very, very big is often very, very big indeed.

The joy of all this is the joy of scale, I think: mad, apocalyptic scale revealed through the most mindless of interactions. The click that launches a potato becomes, several hours later, the click that plays billiards with planets, that brings the fate of the entire universe into the balance. Spaceplan goes much further than I was expecting it to go. It has multiple crescendos, false-endings, plot twists.

And still, days deep in it, with fresh revelations drawing me closer to what feels like it might be, it must be, the real ending, a curtain drop of transcendent proportions, I find myself pulling away once more.

"I hope this doesn't get too tedious," Spaceplan says to me, long, long after we all know that it has gotten far too tedious, and that it has only been allowed to get to this state because something in me, something, hopefully, in all of us, craves the tedium. Click, off, gone.